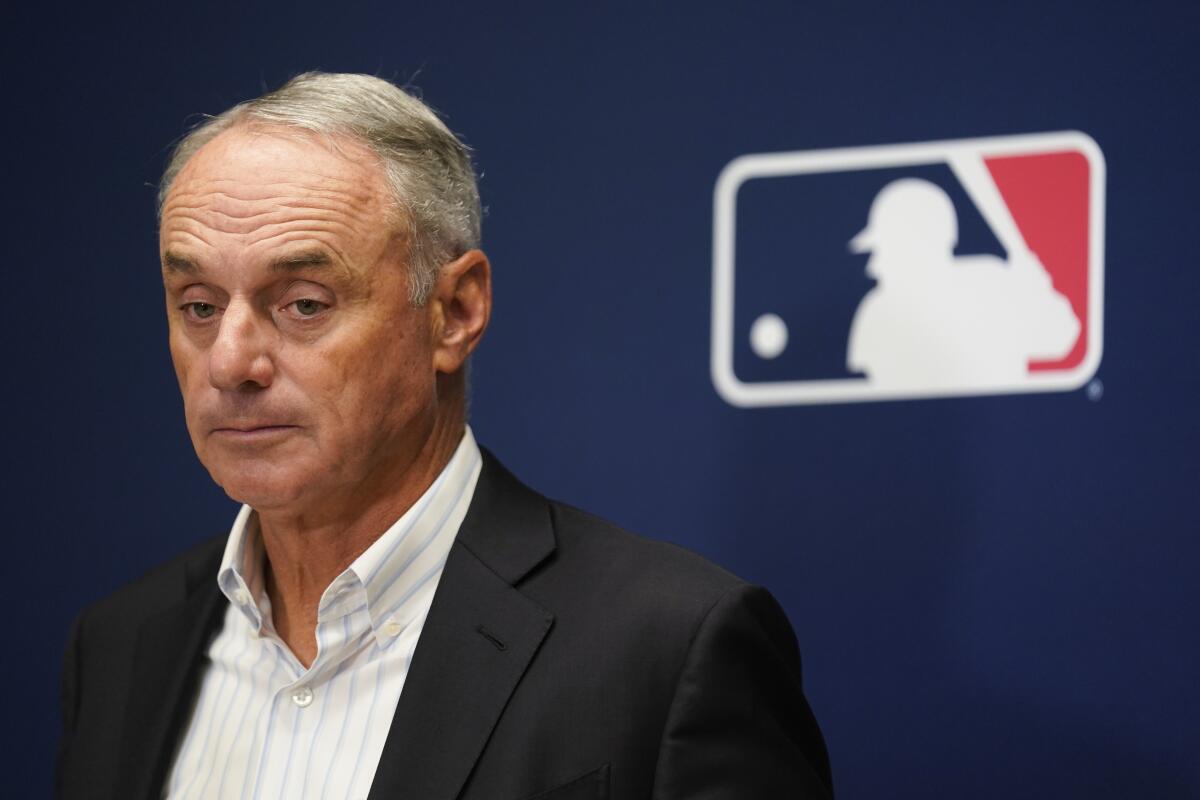

Column: Rob Manfred is a labor lawyer. Now minor leaguers could unite against MLB

Rob Manfred did not make his name in baseball as a former player, as a general manager or team president or team owner, or as a marketing or broadcasting executive.

Manfred, the commissioner, made his name as a labor lawyer. On his watch a quarter-century of labor peace collapsed last December, when owners locked out players. And, in a dramatic move late Sunday night, the Major League Baseball Players Assn. declared its intention to represent minor league players.

If enough minor league players agree, Manfred and the major league owners would no longer decide for themselves how much minor leaguers should be paid. Collective bargaining would also determine if minor leaguers should continue to be bound to the major league team that signed them for as long as seven years, and what standards should be set in areas from housing and nutrition to licensing and merchandising.

“Poverty wages, oppressive reserve rules, discipline without due process, ever-expanding offseason obligations, appropriation of intellectual property, substandard attention to player health and safety, and a chronic lack of respect for minor leaguers as a whole (to name just a few) — these cancers on our game exist because Minor League Players have never had a seat at the bargaining table,” MLBPA executive director Tony Clark said in an email to agents, first obtained by the Athletic. “It’s time for that to change.”

In a wide-ranging interview, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred talks about baseball’s biggest issues, including the Angel Stadium saga and rising costs for fans.

That could have changed without the intervention of the players union, but the reforms Manfred and the owners have made within the minor leagues largely have been reactive rather than proactive.

When a group of minor leaguers sued MLB for violating the federal minimum wage law in 2014, MLB responded by lobbying Congress for an exemption to the law. Without an exemption, MLB warned, minor league teams could be eliminated.

In 2018, Congress approved the exemption. MLB eliminated 43 minor league teams anyway.

This year, as the Senate Judiciary Committee explored whether to strip MLB of its antitrust exemption, Manfred suggested that action could result in the elimination of even more minor league teams.

In the meantime, in 2020, a nonprofit organization called Advocates for Minor Leaguers had formed, using social media to show the cramped quarters and stingy meals to which minor leaguers are accustomed. In response, for the first time, MLB agreed to provide housing for minor leaguers.

And, after a judge ruled that minor leaguers should be considered year-round employees and should be paid for spring training as well as the regular season, MLB agreed to pay $185 million to settle that 2014 lawsuit.

That agreement did not quell rising public pressure. In July, with regard to the antitrust exemption, Manfred told me: “I can’t think of a place where the exemption is really meaningful, other than franchise relocation.” The Senate Judiciary Committee took note, and committee Chairman Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill.) told me he planned to call Manfred to a hearing in Washington, probably in September or October.

Meanwhile, at the All-Star Game that month, Manfred said this of minor leaguers: “I reject the premise that they are not paid a living wage.” Beyond salary, he referenced signing bonuses and free housing.

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred wrote to the Senate Judiciary Committee that players could lose job opportunities if baseball loses its antitrust exemption.

On the same day, Harry Marino, executive director of Advocates for Minor Leaguers, said this of major league owners: “I think the league is very nervous.”

With that crescendo of criticism, the MLBPA offered to do what it had long resisted: represent the minor leaguers. The MLBPA had helped minor leaguers in other ways, but the potential for conflict with the major leaguers had been a hurdle.

“In negotiations, everything is essentially traded dollar for dollar,” pitcher and MLBPA representative Andrew Miller told me in 2018. “There might be a possibility for us to pressure the MLB side to raise wages on the minor league side. However, we would probably be sacrificing, say, arbitration, or some sort of dollars that are being spent on us elsewhere. That is just the reality of the deal.”

On Sunday night, according to the Athletic, Miller was one of the voices on video promoting the MLBPA plan to minor leaguers. An MLBPA official said no one on the union’s executive board voted against the plan.

On Monday, the union publicly announced its decision to organize the minor leaguers, and Advocates said it would suspend operations, as its staffers had accepted positions within the MLBPA. Advocates and MLBPA leaders had quietly worked on the organizing plan for months, according to a person familiar with its progress.

The MLBPA plans to establish a separate bargaining unit for the minor leaguers, as their labor agreement would be independent of the current collective bargaining agreement for major leaguers.

The salary for a triple-A player starts at about $14,000. The salary for a player at the highest level of hockey’s minor leagues starts at about $52,000. The minor leaguers in hockey are unionized, and now the minor leaguers in baseball might be too.

That does not mean minor leaguers in baseball will get better salaries next season. On Sunday night, the MLBPA asked minor leaguers to sign a card authorizing the union as their representative in collective bargaining. If 30% sign, according to federal labor law, minor leaguers would vote on whether to join the MLBPA, with a majority vote required.

If a substantial number of minor leaguers sign, the MLBPA could ask MLB to recognize the minor leaguers as unionized without a vote, and negotiations on a contract could start. But MLB — like any employer — could demand a vote. In the time preceding that vote, MLB — like any employer — could try to persuade minor leaguers they would be better off without the union.

Under Manfred, the owners have improved minor league wages and working conditions, but reluctantly, and not without external pressure. That track record indicates the owners might be better off working with the union here, rather than fighting the union and trying to force a vote. The owners, remember, already lost $185 million fighting minor leaguers.

An MLB campaign to resist a union could amount to: “Trust Manfred; he’ll do the right thing.” In that case, here’s betting a piece of metal that major leaguers would rush to rally around the minor league cause.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.