Commentary: Caleb Williams’ father would be wise not to turn USC QB into a modern Marinovich tale

The recent story in The Times about Caleb Williams, projected USC star quarterback, brought to mind words about history repeating itself. The most-used quote on that subject is from Harvard-educated Spanish author/philosopher George Santayana, who wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Williams transferred from Oklahoma to USC after last season. At Oklahoma, Williams took over for preseason Heisman candidate Spencer Rattler, and did well. His coach at Oklahoma, Lincoln Riley, jumped ship to take over at USC, and Williams followed.

There is little unusual about that. This is the age of transfer portals, glamour and greed in college football. What is out of the ordinary is the extent, as documented in The Times story, to which Williams’ father, Carl, has gone to build his 19-year-old into a brand. Not an athlete. Not a student. Not just a good person. A brand.

This branding is no longer illegal in the cesspool formerly known as college football. The days of Little Johnny starring on his high school football team, happily accepting a scholarship to go to school for free, and playing his heart out for Big State U in return, are long gone. There will be some who still do that, but if they are unable to “build their own brand,” we won’t hear much about them. Their consolation prize will be actually living the cliché that college coaches have foisted on us for decades. They will have gone to school and “built their character.” What a concept.

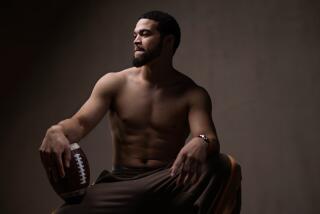

Caleb Williams and his father share the strategies they have used to put the USC quarterback in the best position to win on and off the field.

This situation came to pass when the NCAA, for years the ultimate greed conglomerate, was found to be illegally keeping its athletes from getting paid for use of their names. It is called NIL: name, image and likeness. If Little Johnny is a big enough star, he can have his picture taken with shoes, shirts, headphones and sports drinks — almost anything that is for sale. He will be endorsing them and the companies that make those products will pay him.

It would seem that the NCAA’s image of greed may have been addressed by shifting the greed to 18-and-19-year-olds.

Which brings us to Carl and Caleb Williams, and, in sort of a retrospective cautionary tale, to Marv and Todd Marinovich.

Marv Marinovich was the captain of USC’s 1962 national championship and ’63 winning Rose Bowl team. He was a down-in-the-dirt, rock ‘em sock ‘em lineman. He married the sister of Trojans star quarterback Craig Fertig, and Marv and Trudi had a son they named Todd. But to Marv, Todd wasn’t only a son, but a science project. Before Todd was a month old, Marv started stretching his hamstrings in his crib. Before he could walk, Marv had Todd lifting medicine balls. He was allowed to eat only healthy food, fruits and vegetables.

Later, after it had all fallen apart, after Todd had starred as a prep quarterback for two Orange County high schools, had gone on to USC and starred there for a year before finding drugs, rebelling and opting out of college for the pros, Sports Illustrated wrote that he had been “the first-ever, test-tube athlete,” that he had been “bred to be a superstar,” and that “all Marv wanted to do was to mold athletes, and Todd was his favorite piece of clay.”

Todd’s troubled college career morphed into a troubled pro career with the Raiders. Soon, there was no career at all, just trips to court and jail on various drug arrests. At one point, the folks running the jail in Irvine, so familiar with Todd’s comings and goings, greeted his most recent entrance by playing the theme from the 1970s hit TV show “Welcome Back, Kotter.”

Todd is 53 now. He works as an artist, and has considerable talent. Marv died in 2020, at 81. He had Alzheimer’s. His daughter, Traci, who has been quoted over the years as saying she was mostly an afterthought to Todd, took care of Marv in his later years, even though he usually didn’t have any idea who she was. “Todd wouldn’t have been able to know what to do [for his father],” she said in the Sports Illustrated article. “He wouldn’t know how to handle things like social security. He never had to do any of that.”

Which brings us back to Carl and Caleb Williams, although the situations are not parallel. Marv Marinovich was not directly seeking the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, although the letters “NFL” certainly had to be on his mind. Carl Williams is not trying to create the next quarterback Adonis. More like the next signal-calling Warren Buffett. The thing that is comparable, however, is the possibility of paternal excess and the damage it can cause.

The recent Times article focused on Carl’s establishment of advisers and agents and marketing and investment firms for Caleb. His NIL stature might be worth seven figures. Maybe it is already. He is endorsing things such as headphones and men’s fingernail art. But he is also, through his father, seeking partnerships, equity positions, corporate stature. This can go two ways: a fine college career that morphs into a fine pro career and lifetime financial security; or a disintegration of it all, triggered by too much pressure.

When LaVar Ball moved to Chino Hills to start a family, he found a planned community that matched his own ambition. A fascinating relationship ensued.

LaVar Ball made two of his three sons from Chino Hills into current good NBA pros with great financial futures, and took along some of the deflected fame for himself to create and promote his businesses. As loud and obnoxious as he was along the way, LaVar’s pushy father-knew-best approach achieved the goals, at least for the moment and at least financially.

Perhaps Carl Williams can do likewise with his son, but with a little less noise and a little more sophistication. Also, with no damage to a football career, a Trojans football team and/or a USC education that can eventually pay even bigger dividends than monthly checks from the fingernail-painting company.

Parental pressure in high school and college sports is oft-abused and occasionally tragic.

One of the best quotes ever uttered on the subject was in tennis, a sport historically abundant in pushy parents. It was 1991, and Pam Shriver was being interviewed at Wimbledon about upcoming star Lindsay Davenport. “I have never met her parents,” Shriver said, “and I love them for it.”

History has lessons for Carl Williams. Don’t make your son your favorite piece of clay.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.