Inside the Orange County ice rink where Nathan Chen and other Olympians trained

The ice rink in Irvine, now a well-scraped path to the Olympics, seemed frozen in time. Notecards wish Nathan Chen, a regular there, good luck and young skaters swiveled to the beat of their coaches’ instructions.

Chen, 22, won a gold medal at the Olympics in Beijing a day earlier, cementing his spot as the top men’s figure skater in the world and the first U.S. man to win gold since 2010. It was a redemptive victory — Chen finished fifth at the 2018 Olympics — that many of his coaches and family members were unsurprised by.

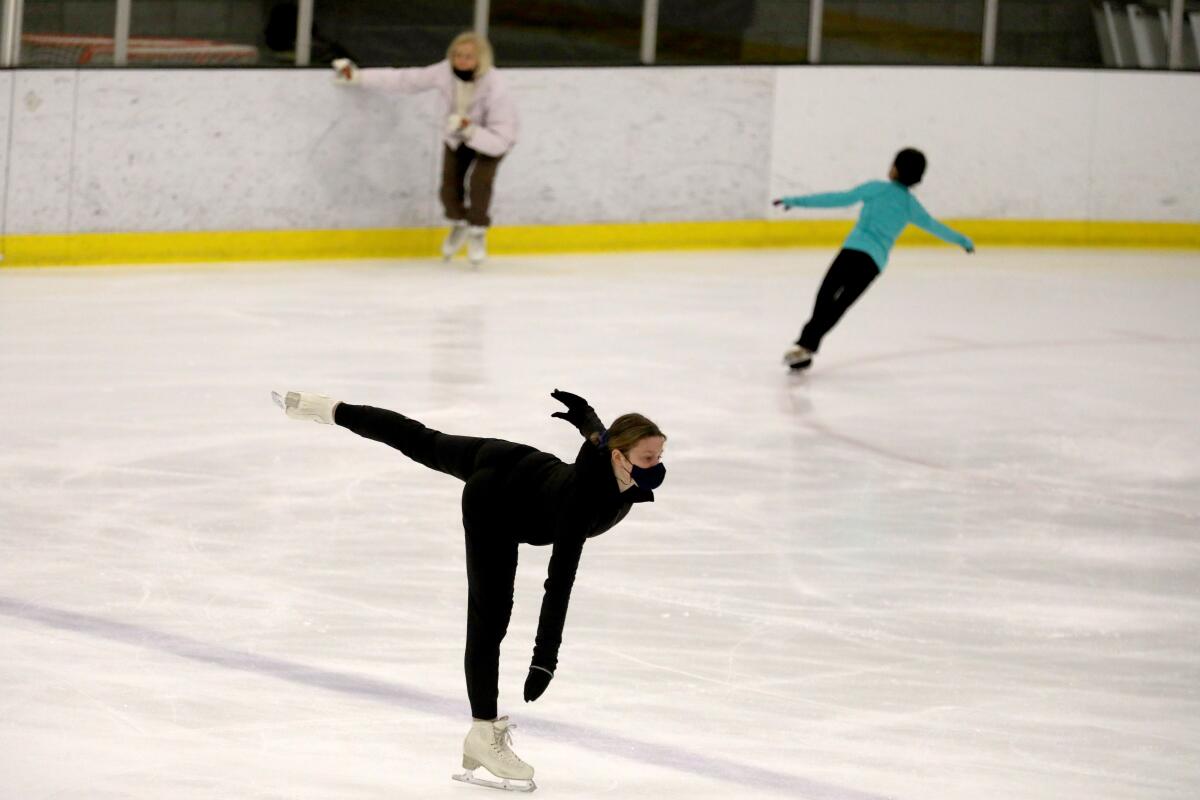

“Last Olympics, he was very technical already, very good in the artistic part,” said Vera Arutyunyan, one of Chen’s coaches, at the Great Park Ice rink where she was leading a handful of young skaters in practice on Thursday.

“He’s different now,” she said. “He’s more mature, he’s a real artist on the ice.”

Great Park Ice, a sprawling, warehouse-like complex the length of two football fields houses four rinks and is home to five Olympians currently at the Olympic Games. The facility, which opened in 2019, is nestled between a residential neighborhood and the massive Great Park outdoor recreation area, not far from the office towers and industrial parks of Irvine.

At around age 12, Chen, then a dedicated ice skater who got into the sport watching his siblings play hockey, convinced his mother that they should move to Southern California from their family home in Salt Lake City. He wanted to turbocharge his training by working with a renowned figure skating coach, Rafael Arutyunyan, now Chen’s main coach and husband of Vera.

In addition to Chen, U.S women’s figure skater Mariah Bell, Czech men’s skater Michal Brezina and U.S. pairs skaters Alexa Knierim and Brandon Frazier all train at the facility, under the tutelage of Rafael Arutyunyan and his team.

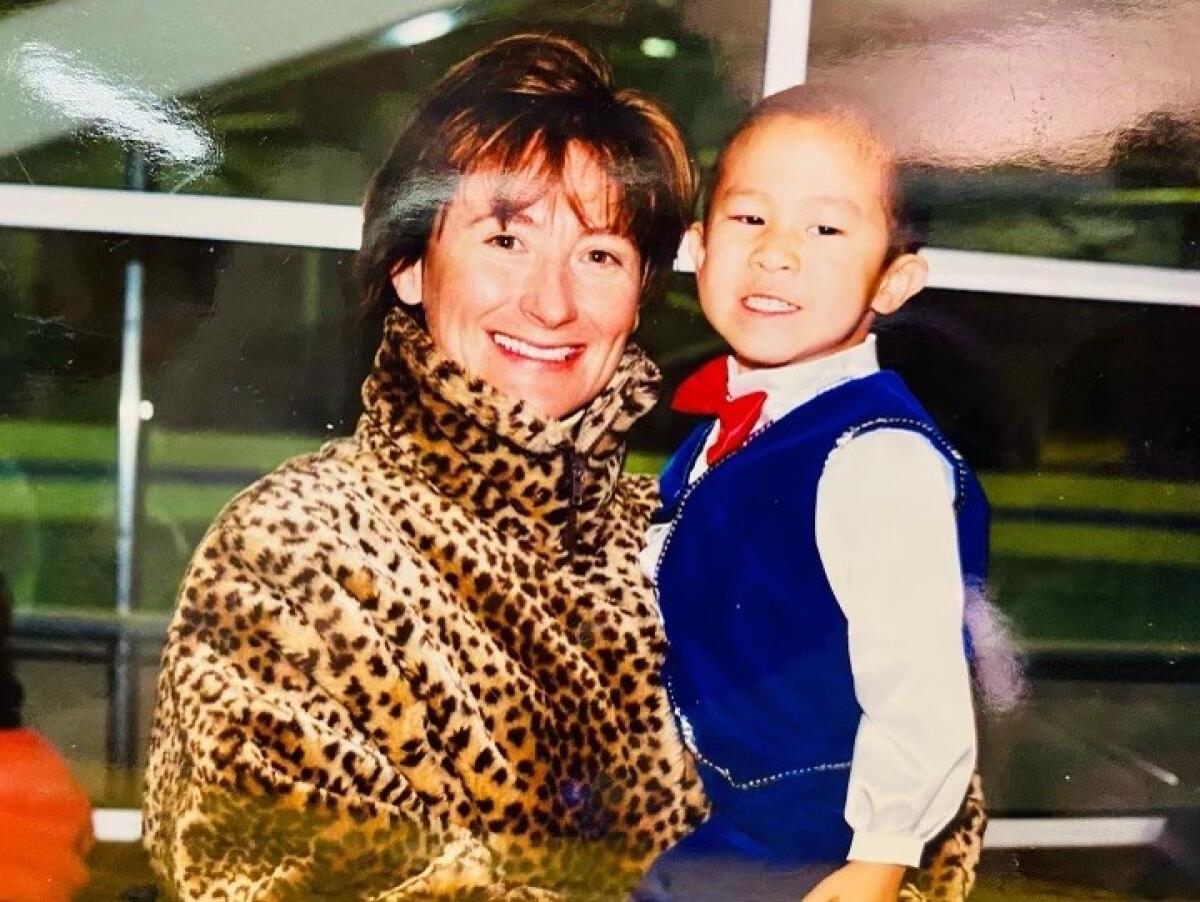

Vera Arutyunyan recalled meeting Chen when he was 10 years old. He was already a hard worker then, she said. She had no doubt about his performance heading into the men’s long program on Thursday as she watched at another coach’s home.

“He was ready,” she said Thursday, surrounded by students and other coaches outside the rink. “Everybody thought it has to be good.”

Inside, the sound of slicing, scraping and swiveling looped, while classical and sometimes upbeat music punctured through on loud speakers.

Notes to the Olympians line the doors of one of the ice rinks. Well-wishes for Chen are plastered across a glass plate from top to bottom: “I hope you win Nathan!” “I’m rooting for you! Get the gold medal!” One note, adorned with a drawing of a crown and a rocket ship, says, “Go Rocket Man!,” a reference to the medley of Elton John songs Chen skated to in his long program.

A handful of skaters who train with Arutyunyan’s team whizzed by as coaches scrutinized their arm placements, knelt to watch skate movement and replayed the opening notes of one skater’s program music.

Chen’s victory solidifies the facility as a place where young people can train to become elite athletes, said Art Trottier, vice president at The Rinks, which includes Great Park Ice. Media requests are pouring in to hear more about Chen’s training facility or to catch up with him when he returns from the Olympics.

In the rafters, there’s a specific tribute to Chen — a light blue banner with his name, depicting his 2018 triumphs: U.S. national champion, world champion and ISU Grand Prix champion. After his turn at the 2018 Winter Olympics, Chen became nearly unstoppable, winning nearly every competition he’s entered.

A coach in a gray sweater held what looks like a fishing pole attached to a harness worn by a young skater who attempted a triple-toe loop. The skating pole harness helps skaters feel more secure in their jumping techniques, part of the constant chase to add revolutions to jumps.

Chen himself is known as the “Quad King” because of his mastery of quadruple jumps in his routines.

“Speed up, speed up, speed up,” Vera Arutyunyan called out to a young skater on the ice, as the skater headed into a jump.

As Chen skated onto the ice in Beijing on Thursday, his mother, Hetty Wang, was glued to the television screen at her daughter’s San Francisco home. She hoped her son would “skate the best he can.”

He did.

“Of course, I’m very, very happy,” Wang said by telephone.

The family spoke with Chen after he finished skating and congratulated him, she said.

After sealing his spot in first place, Chen told the “Today Show” that “absolutely none of this would be at all remotely possible” without his mother’s support.

“Since Day 1, 3 years old, I stepped on the ice, and she’s been by my side ever since,” he said.

Wang reflected on the long drives with Chen when he was a child from Salt Lake City to training in Lake Arrowhead with Arutyunyan, his coach.

The family was under financial strain from the frequent trips and training, she said, calling the effort to save both time and money “very hard.”

“We tried to drive during the night and so we would not need to stay overnight, and get there in the morning so he can start skating,” she said. “He could sleep in the car. I’m driving and sometimes, I would be tired and find a gas station and take a nap.”

The pair would stay in Lake Arrowhead for days, sometimes weeks before the decision to move to Southern California. In addition to Lake Arrowhead, Chen would go on to train with Arutyunyan in Artesia, Lakewood and finally Irvine.

It wasn’t always clear to Wang that the boy who stepped onto the ice as a toddler would eventually become an Olympic athlete. He wanted to try the sport, starting at age 3, because he watched his siblings play hockey. He had dreams of being a goalie.

After the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Chen was among nearly 480 people of different ages who signed up to learn to skate at the Salt Lake City Sports Complex. A tiny Chen came wearing a long jacket that came to his ankles and oversized white skates, recalled Stephanee Grosscup, his first skating coach.

“He was shy,” Grosscup, 61, said. “He wouldn’t speak much but I would say, ‘Do one foot balance’ and he would do it.”

Grosscup said Chen was the best toddler she’d ever taught — a “prodigy.”

She knew he would eventually outgrow her (“he’s meant for bigger pastures than what I had to offer,” she said) and felt it was her duty to instill in him not only a strong foundation of basic skating skills but to ensure that his love of the craft remained intact, a joy he could depend on.

On Thursday, when it came time for Chen’s program, Grosscup watched a livestream on her home computer. She followed each jump and spin, and kept an eye on Chen’s facial expressions.

“Where I knew things got so amazing was when he landed that quad lutz and he got the look on his face like ‘I’m going to lay this down,’” she said. “Not only is he doing this, he’s enjoying every single moment.”

After he clinched the gold, she cried.

Fellow skaters and coaches in Irvine said they were nervous for Chen before his final routine. One said a prayer before Chen took to the ice. They described him as friendly and humble, someone who prefers when no one notices him and likes to focus on his job.

“He always manages to do well, he works very hard,” said Eric Sjoberg, 20, the 2020 U.S. junior silver medalist, who has trained with Chen for a long time. “I wasn’t worried at all.”

Skater Melania Delis, 16, said she admired Chen’s work ethic. “I look up to him a lot,” she said.

Inga-Nissa Lee-Eichenwald, 13, took lessons with Chen last summer, when he helped her learn a triple salchow jump. He’s particularly good at demonstrating and explaining, she said, and gives them a sense he relates to them.

“He’s really chill,” she said of the three-time world champion and six-time national champion.

Like Chen, Lee-Eichenwald and her mother moved to Southern California from their home in Montana so she could train with Arutyunyan’s team. “It’s really inspiring for everyone, and it’s an example for everybody to know how to work and how to progress,” she said.

Life can change quite a bit after winning an Olympic gold medal. Just ask Evan Lysacek, the 2010 Olympic champion and the last U.S. man to win the figure skating gold until Chen’s victory this week.

“He’ll be able to just diversify what he’s doing, going from the training rink nonstop every minute of every day to now probably having a lot of media attention and some really cool offers,” Lysacek said. “I was a bit private and enjoyed the attention and the fun that came along with winning but then was perfectly happy to get back to a private life.”

Lysacek has known Chen and his mother since Chen was young, when both skaters were training in Lake Arrowhead. Lysacek’s life is now far removed from sports — he and his wife develop residential properties together and started a venture capital firm — but he’s kept up with Chen’s career and spoke with him before the Games.

After Chen’s performance, there was “so much excitement” in a group chat Lysacek is in with other U.S. Olympic gold medalists, he said. As of Thursday afternoon California time, Chen wasn’t on the chat chain yet, but he had definitely joined a “very exclusive club,” Lysacek said.

Times librarian Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.