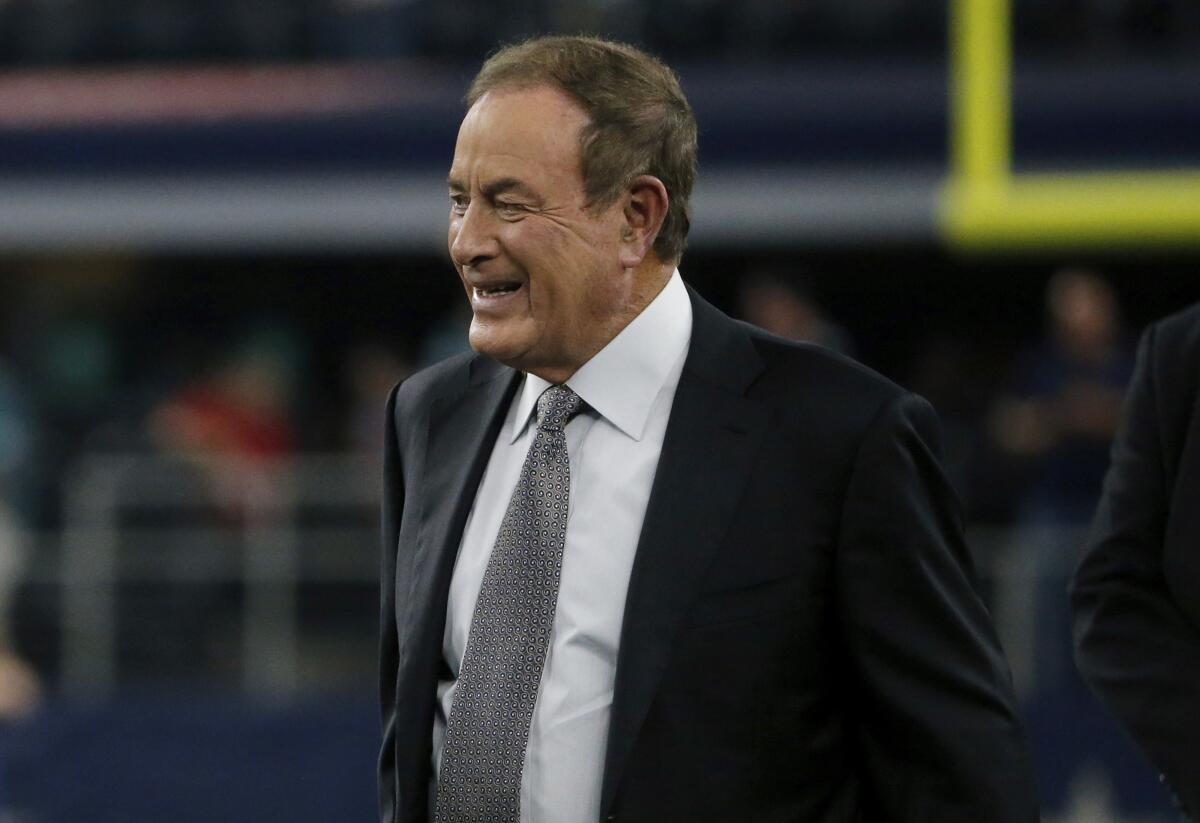

‘One hell of a ride’: Al Michaels on his 56-year Super Bowl journey, in his own words

Everyone knows the voice. NBC play-by-play announcer Al Michaels has called some of the greatest games in NFL history, and now with the Super Bowl in Los Angeles, he’ll finally get to work one in his hometown. He was in the Coliseum stands for the first Super Bowl — then the AFL-NFL World Championship Game — and recounted those memories and more for Times NFL writer Sam Farmer. Here, in Michaels’ words, are his thoughts on the league’s biggest stage:

Our country’s No. 1 sports event is coming back to Los Angeles on Feb. 13, and personally, it will provide a special thrill for me. So Fi Stadium is a 25-minute ride from my home (OK, if there’s a Sigalert, more like 75 minutes), and it will mark the 11th Super Bowl I’ve called on either ABC or NBC.

And it’s personally extra significant. On Jan. 15, 1967, I was at the Los Angeles Coliseum for the first one.

I was 22, had graduated from Arizona State the previous spring and gotten married to a girl I’d met in the 10th grade at Hamilton High School. We tied the knot on Aug. 27, 1966, and Linda is the love of my life. I went to the game with my younger brother, David, and we were big fans of the upstart American Football League.

The Super Bowl typically brings in money to its host city from tourist spending, big parties and local fans — but just how much is a contested question.

There was a big family connection to the AFL. Seven years earlier, our dad had gone to work for MCA and was involved in starting their sports division, negotiating television rights with the networks and representing athletes. He helped broker the original AFL television contract in 1960 with ABC. It was something like $2.1 million for the ENTIRE season! For a little perspective, some 30-second commercials for this year’s Super Bowl will be sold for approximately $6 million. Each!

I remember one night, that contract sat on our kitchen table in Cheviot Hills. I had no understanding of the legalities, but there it sat.

The AFL appealed to me because the NFL was the established big boy and the AFL was the “rascal” league. Always having had a little bit of rascal in me, I could relate. I saw every home game of the Los Angeles Chargers in 1960 and, through my father, got to meet most of the [AFL] owners and top executives, including Lamar Hunt, Ralph Wilson, Barron Hilton and Bud Adams. One afternoon, we went over to the Chargers’ camp and I caught a few passes from their original quarterback, Jack Kemp. An unbelievable thrill for a 15-year-old! I even ran a few routes. Cris Collinsworth I was not.

I met Al Davis too. He was a young up-and-coming assistant coach just a few years before he would become AFL commissioner and owner of the Raiders.

The first Super Bowl was known at the time as the AFL-NFL World Championship Game. My father was out of town, but he got great tickets for my brother and me on the 45- yard line about 20 rows up on the north side of the Coliseum. The NFL champion Green Bay Packers faced the AFL champion Kansas City Chiefs on a beautiful day in the middle of January in front of a crowd around 62,000 and 33,000 empty seats.

My brother and I were nervous. We thought the Chiefs could get blown out and make the AFL look like the rinky-dink operation most NFL fans thought it was. So we felt hopeful when the Chiefs hung in there and trailed only 14-10 at halftime. I went out for a hot dog and saw a guy in a Chiefs shirt. I said: “We’re hanging with them. We’re as good as they are.” He said, “Damn right.”

The chickens came home to roost in the second half. Green Bay outscored the Chiefs 21-0 to win 35-10.

At that point, I couldn’t even dream that pro football would become such a huge part of my life. There’s a lot of irony when people talk with me about my broadcasting career and bring up three moments — the 1980 Winter Olympics when the U.S. [men’s hockey] team upset the vaunted Soviets on their way to a crazily improbable gold medal, the earthquake that interrupted the 1989 World Series and my live narration of the O.J. Simpson slow-speed Bronco chase in 1994. And yet for almost half my life — 36 years — I’ve called the NFL in prime time. When it’s said “time flies when you’re having fun,” I’ll attest to that in spades. It’s all gone by at warp speed.

My first Super Bowl at ABC was as the pregame, halftime and postgame host of the 49ers-Dolphins meeting at Stanford Stadium following the 1984 season. Montana vs. Marino. Jim Lampley was my cohost, and our partners were Tom Landry and O.J. Simpson. Linda and I were living in Menlo Park at the time, so it was an eight-minute drive to work.

In 1986, Dennis Swanson, the president of ABC Sports and to whom I’ll be forever grateful, made me the play-by-play announcer on “Monday Night Football.” The following season, I called my first Super Bowl with Frank Gifford and Dan Dierdorf. It was the Broncos and Washington in San Diego. Denver led 10-0 after the first quarter. Up to that point — 21 years — most of the Super Bowls had been snorefests. I thought maybe we’re due for a gem. So then Washington scores 35 points in the second quarter en route to a 42-10 thrashing. At halftime, Dierdorf and I looked at each other and simultaneously said, “What the hell happened?”

My second Super Bowl was in Tampa [Fla.] three years later, just days after we had gone to war with Iraq in Operation Desert Storm. Security was tight — it was the first time I can remember concrete barriers encircling a stadium. We weren’t allowed to fly a helicopter, a small plane or a blimp above the stadium, so our aerial shot was taken with a telescopic lens atop a hotel about a half-mile away.

The night before the game, Dennis Swanson told Frank, Dan and me that SWAT team members wanted to meet with us. They wanted us to know what we were supposed to do if terrorists invaded the broadcast booth and took the three of us hostage. Seriously. It was all I could do to suppress a laugh. I walked out with Dan, who said, “Whoa, that was really something.” Then I looked at my partners and said: “Guys, you know what this is about? In the guise of protecting us, all these characters are looking for is a way to get into the game with a 50-yard-line vantage point for free.” To which Frank responded — “1,000%!” The Giants beat the Bills 20-19 when Scott Norwood missed a 47-yard field goal at the end.

Four years later, we’re in Miami for the 49ers against the Chargers. San Francisco was favored by 18 or 19 points, the largest spread in the game’s history. Apart from Steve Young throwing six touchdown passes, there was not much drama. Until the end. On the last play of the game, Chargers quarterback Stan Humphries launched a pass into the end zone. If it was caught, the Chargers would cover the spread. It wasn’t, but I couldn’t resist saying when the pass was airborne that “all over America, hearts are beating furiously.”

I’m often asked if I get nervous calling a Super Bowl. I think anxious is the word. The buildup lasts forever, and you just want to get started and, like a racehorse, come out of the gate cleanly. Obviously, the audience is gigantic, but like the players on the field, you can’t get overwhelmed. It’s also good to have perspective. One way to look at it is if there are 100 million people who tune in and there are roughly 330 million people in the United States, that means 230 million people are NOT watching. Also, after announcing close to 1,000 football games — NFL, college football for many years before that and lots of high school games when I started my career in Hawaii — there’s a comfort zone obviously born of experience. One thing that’s a little different is focus. I think the synapses of your brain open wider. Things seem clearer, and sometimes it seems like the naked eye is seeing the field in 4K. I’ve had this discussion with Joe Buck and Jim Nantz, and their feelings parallel mine. The three of us have done the last 17 Super Bowls, and I think we all have rabbit’s feet dangling from our pockets. It’s one hell of a ride!

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter

If there’s pressure, you just want to make sure you’re getting it right. Recordings of dramatic game-ending plays live forever, and you don’t want to screw it up. In the Rams-Titans game at the end of the 1999 season, the game ended when Rams linebacker Mike Jones tackled the Titans’ Kevin Dyson at the one-yard line when a touchdown and extra point would have sent to game to overtime. In the Patriots-Seahawks Super Bowl after the 2014 season, Malcolm Butler saved the game for New England by intercepting a Russell Wilson pass at the goal line with seconds remaining. In both instances, those brain synapses opened wide enough to get everything right. And truth be told, my spotter, the incomparable “Malibu” Kelly Hayes, was able to confirm both plays instantaneously as if our brains were working as one. There’s nothing like working together for 45 years!

So many thrills — Super Bowl XLIII, Arizona vs. Pittsburgh. Two epic plays: James Harrison’s 100-yard interception runback for a touchdown as the clock ran out in the first half and Santonio Holmes’ unbelievable catch of a Ben Roethlisberger pass to win the game in the waning seconds. That may be my favorite football telecast ever, and it turned out to be John Madden’s last game. The great man retired unexpectedly shortly thereafter. There was Philadelphia vs. New England four years ago with the Philly Special highlighting the highest-scoring Super Bowl ever.

Can’t wait for [this year’s game]. Got my gang all here — Cris Collinsworth, Michele Tafoya, our producer Fred Gaudelli, director Drew Esocoff and so many of our production and support people who are the best of the best. We’re ready to put on a great show for you. All we need is high drama. Whoever wins, wins. I have only one rooting interest — triple overtime.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.