Bob Goalby was just a few months shy of his 91st birthday on a warm winter day in the Palm Springs suburb of La Quinta, when he ambled into a restaurant for lunch and an interview with a magazine writer.

He used a walking stick that used the head of a golf driver as an anchor. Because he had an infection in one leg, one shoe was size 12 and the other size 14. He smiled, said he was happy to be there, “happy to be anywhere,” and perused the menu.

The interview was not going to be about his part in what remains a historic moment in the game of golf, the 1968 Masters he won when another player signed an incorrect scorecard. This time, he was being asked to talk about the first Palm Springs pro tour event, the $70,000 Palm Springs Classic in 1960, where he finished third as Arnold Palmer won the first of his record five wins in the desert.

Goalby was fine with the topic but made it clear that he understood, and was fine with, his unerasable spot in golf lore.

“I sure know what the first paragraph of my obituary will be,” he said.

So, there it was last week, when Goalby died at 92 at home in Belleville, Ill. There was no escaping it. Goalby had won almost $700,000 in a pro career that had spanned three decades and at a time when $700,000 was still a lot; had won 11 times and finished second in both the U.S. Open and PGA; had been influential in starting what is now the Champions Tour; is in three different Halls of Fame, and was the golfing patriarch of a family that includes prominent players Jay Haas and his son, Bill.

There it was, in all publications. The first paragraph. The 1968 Masters. Roberto de Vicenzo.

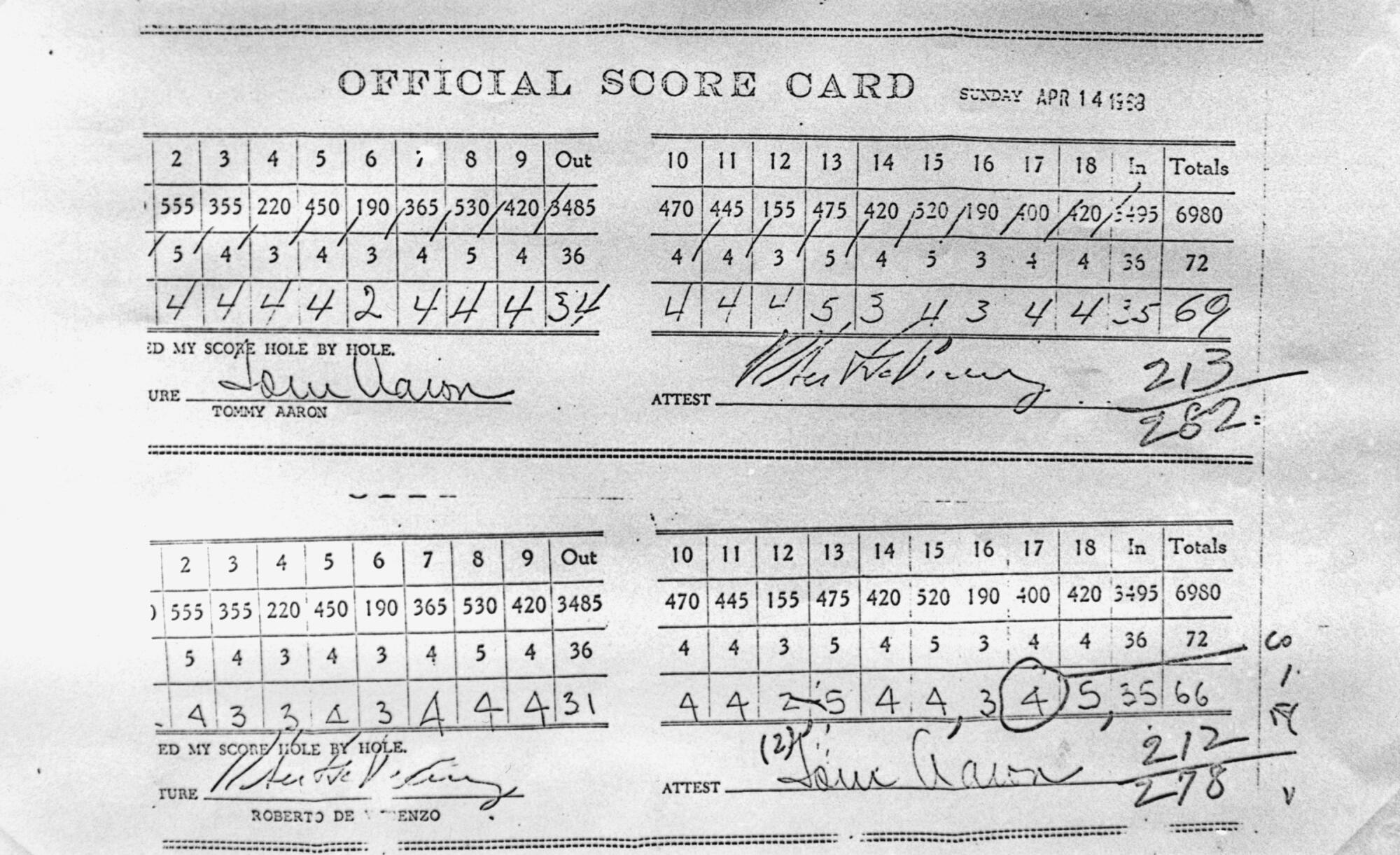

Goalby was a marked man, catapulted into history with the pencil stroke of another player named Tommy Aaron, on behalf of De Vicenzo. Aaron had played with De Vicenzo on that last day of the Masters, and as the rules dictated, kept De Vicenzo’s scorecard and De Vicenzo kept Aaron’s. De Vicenzo made a par three on the 17th hole, Aaron put down a four , and when De Vicenzo signed the erroneous scorecard, meaning he had accepted that score, the extra stroke bounced him out of a playoff with Goalby.

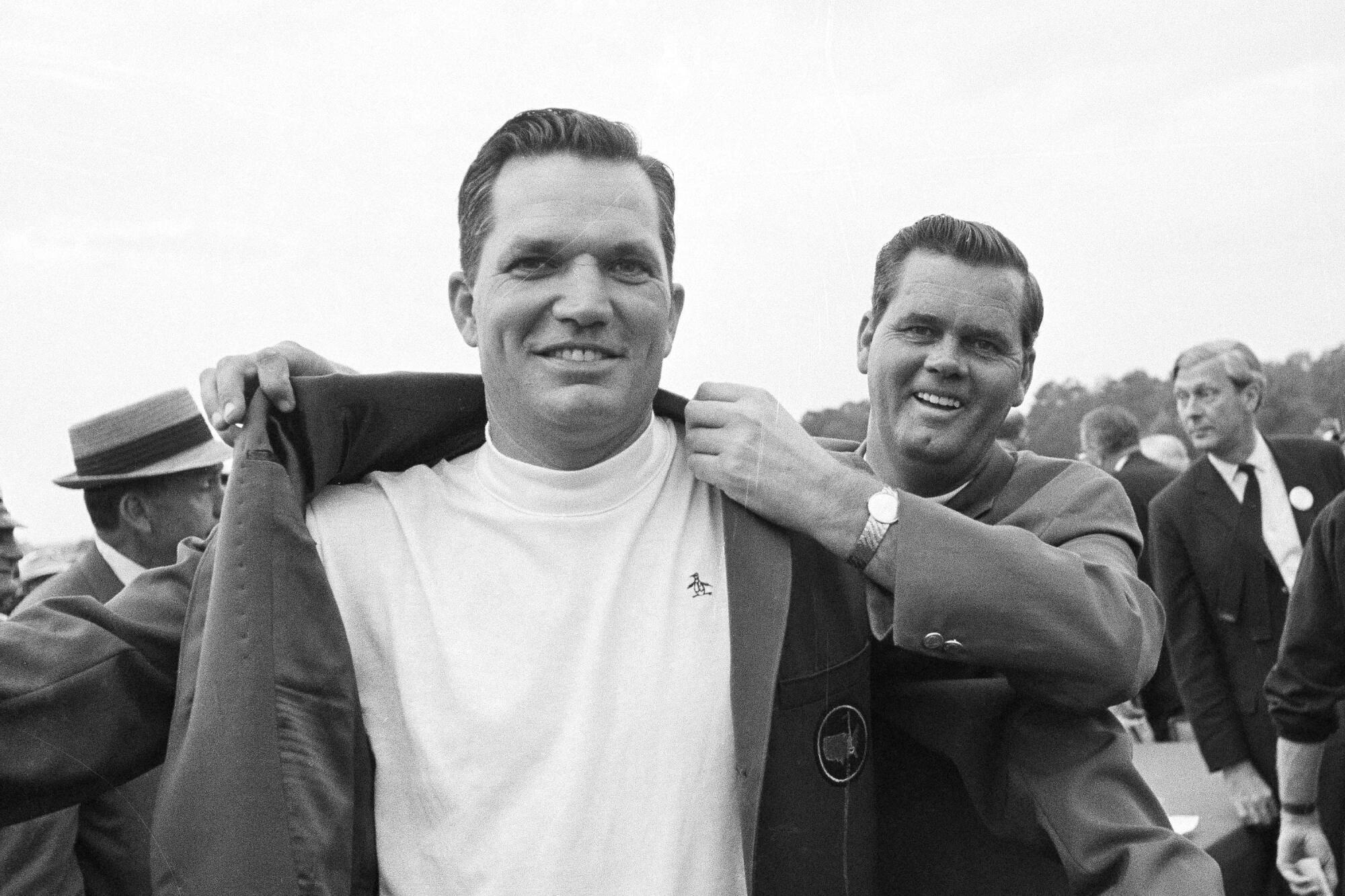

Bob Goalby was the Masters champion. He had reached the sport’s holy grail. It was meant to be a moment of total joy, a fulfillment of dreams, a feeling of unabashed accomplishment. For Goalby, immediately and for years to come, it was a lot of that, but also a lot of confusion and dismay.

Bob Goalby says he has been getting lots of phone calls the last few weeks.

An element of the sports public somehow saw Goalby’s Masters title as something marred, not properly earned, something stained. He had won cheap, he wasn’t that good, just lucky. Letters to newspaper sports pages railed against the injustice of it all. Somehow, the sacredness of the Masters had been soiled. Had it happened in the current era of the internet, there would have been reports of several injuries as clueless typists raced down the basement stairs of mom’s house in their pajamas to get at laptops.

Goalby weathered the storm with grace and some ongoing confusion. Why was nobody commenting on the three-iron he hit to within six feet for an eagle on the rugged par-five 15th, a shot that later brought a letter from none other than Bobby Jones, who called it one of the best shots he had ever seen? Why did no one seem to remember Goalby’s scare-you-to-death, four-foot putt for par on the 18th hole that turned out to be the winning stroke?

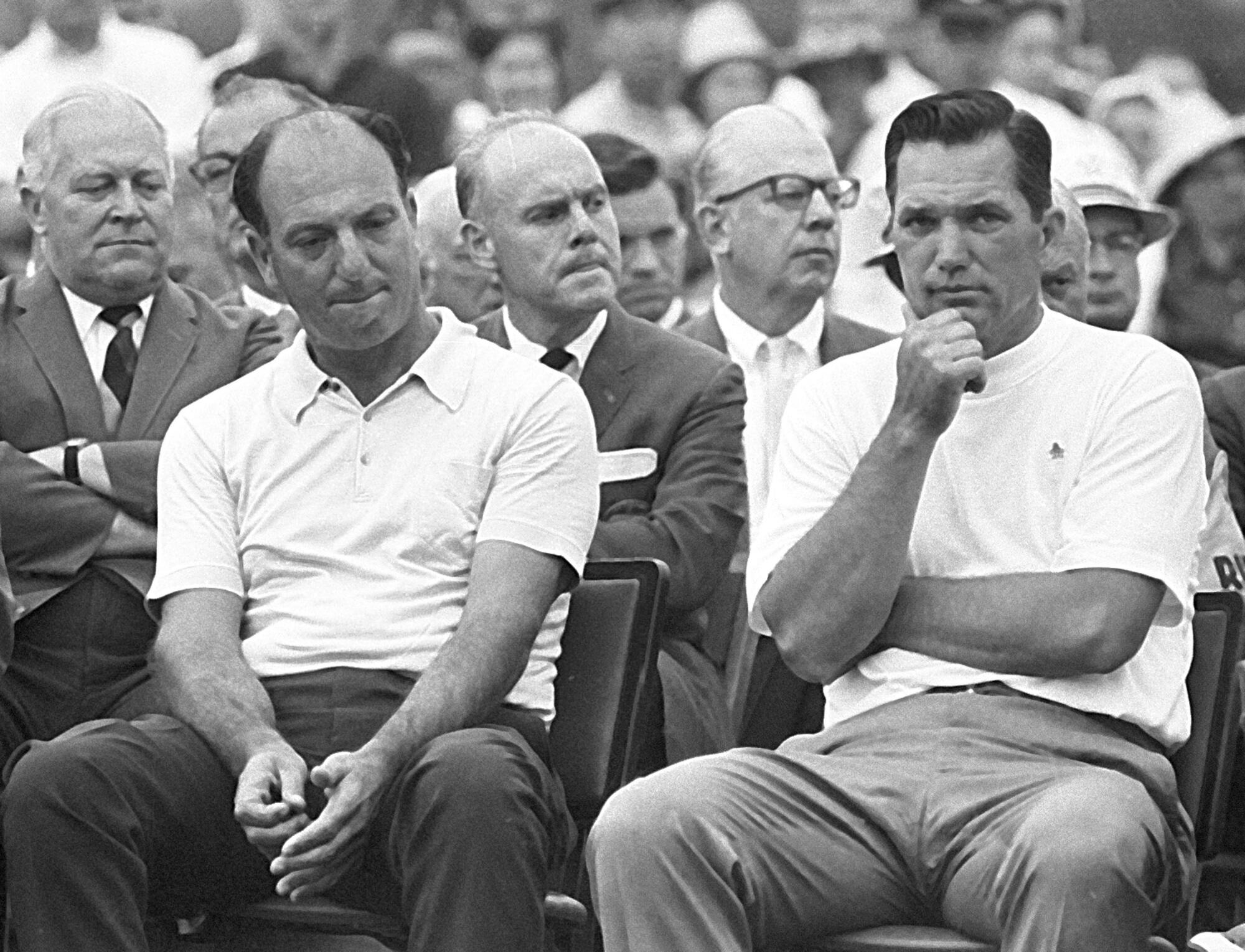

Goalby picked the ball out of the hole after that putt and headed to the scoring area, assuming the putt had gotten him into a Monday playoff. He saw De Vicenzo still sitting at a picnic table where the scoring was done and wondered about that, because the Argentine had finished a half hour before him. Now, golf scoring areas are tents or buildings designed for privacy. Back then, the players at the Masters sat at a couple of picnic tables out in the open and marked their cards.

Goalby recalled years later that, despite thinking it was odd for De Vicenzo to still be sitting there, he wandered past and said to him, “Well, I guess I’ll be seeing you in the playoff.” De Vicenzo said nothing.

The award ceremony was glum. At one point, Goalby patted De Vicenzo consolingly on the knee. But before Goalby even got to put on the green jacket, critics and arm-chair quarterbacks were turning blue. The purists said that the integrity of golf rules should have, and did, win out. Others felt that something as important as the Masters should be decided with a club, not a pencil.

De Vicenzo may have summed it all up best, speaking with the press after realizing his mistake.

“What a stupid I am,” he said, delivering a quote heard ’round the world and featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

Interestingly, De Vicenzo, who had already won a major title at the ’67 British Open, cashed in nicely as a spokesman in a series of ads for Avis, the car rental company that branded itself as being No. 2, but trying harder. Also interestingly, Tommy Aaron won the 1973 Masters.

Goalby simply outlived the critics and never held onto any bitterness toward them. He and De Vicenzo, who died in 2017, saw each other frequently on the tour and even teamed to play a couple of tour doubles events.

“We never talked about it,” Goalby said. “Never once.”

It is somehow fitting that Goalby died the week of the pro tournament in the desert, the Bob Hope Desert Classic that became the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic and several more things before becoming, at least for now, the American Express. Goalby never won it, but bought a home at the Lakes Country Club in Palm Desert in 1974 and alternated between there and Belleville for decades. His older sister, Shirley, is the mother of longtime pro golfer Jay Haas, who won the 1988 desert tournament with his uncle Bob walking the fairways with him as a TV broadcaster. Haas’ son, Bill, has won the desert tournament twice and played in this year’s event but did not make the cut.

“My uncle Bob had a great life,” Bill Haas said after his round Friday, “and just about everything I’ve learned about the game has probably trickled down from him through my dad.”

A somewhat startling statistic emerged in the wake of that magazine interview two years ago. In the first 60 years of the desert tournament, the combination of Bob Goalby, Jay Haas and Bill Haas had won $4,280,701, or 3.4% of all money awarded in the tournament.

In that 1960 Palm Springs Classic, Goalby won $3,350 for his third place. It was, to that point in his career, his biggest paycheck.

For winning the 1968 Masters, he got $20,000, a green jacket and more headaches than anybody deserves for such a great achievement.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.