MLB clubs vote to start 2020 season after players reject latest offer

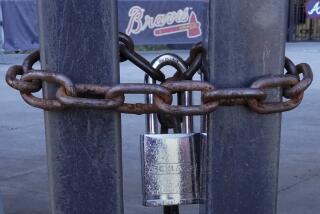

Unable to forge an agreement between owners and players on compensation, Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred exercised his authority Monday to impose a pandemic-shortened regular season — expected to be 60 games — without fans in stadiums.

Manfred’s mandate was issued after nearly three months of contentious negotiations spurred by the owners’ demands for players to take additional pay cuts to help cover the financial losses teams would incur from playing games in empty stadiums. Players pushed for a longer season and full prorated salaries, regardless of how many games were played.

The players’ union rejected the owners’ latest 60-game proposal Monday afternoon, one that would have included an expanded postseason format, a universal designated hitter, 104% of prorated salary for players and a guaranteed $25 million in playoff pools in 2020.

MLB then released a statement stating clubs had “unanimously voted to proceed with the 2020 season under terms of the March 26 agreement” and asking the union to provide two pieces of information by 5 p.m. (EDT) Tuesday: whether players will be able to report to training camp in their respective cities by July 1 and whether the union will agree on the health and safety protocols “necessary to give us the best opportunity to conduct and complete our regular season and postseason.”

The season is expected to start around July 24.

The move came despite Manfred’s last-ditch effort to broker a deal in the wake of a five-day exchange of accusations and insults that began June 10 with the commissioner saying, “We’re going to play baseball in 2020, one hundred percent,” and Major League Baseball suggesting June 15 it might cancel the season.

A break in the stalemate appeared to come last Tuesday when Manfred flew from New York to Phoenix for a four-hour face-to-face meeting with MLB Players Assn. head Tony Clark and made the owners’ first proposal that included full prorated salaries for players.

By Wednesday, Manfred said the sides had “a jointly developed framework that we agreed could form the basis of an agreement” for a 60-game regular season and an expanded postseason that would have included 16 teams, up from the usual 10.

But players deemed a 60-game season too short, and in countering with a 70-game proposal on Thursday, Clark said it was “unequivocally false to suggest that any tentative agreement or other agreement was reached in [Tuesday’s] meeting.”

The owners rejected the 70-game proposal. The players then rejected the owners’ 60-game proposal by a 33-5 vote of its executive committee Monday afternoon, leaving Manfred little choice but to impose a shorter season in which players will receive full prorated pay but for fewer games than they hoped to play.

MLB officials say other season plans could be considered amid coronavirus outbreaks; owners tell players’ union they won’t move off 60-game season.

The move is expected to prompt the union to file a grievance over salary lost by players in a fairly bargained season, a threat that Manfred has said the union has put at about $1 billion. The other alternative — canceling the season entirely — would have left the sport dark for 18 months.

“While we had hoped to reach a revised back to work agreement with the league,” the union said in a statement, “the players remain fully committed to proceeding under our current agreement and getting back on the field for the fans, for the game, and for each other.”

The league is expected to be realigned into three 10-team regional divisions, with teams facing opponents only in their division to minimize travel, so the Dodgers and Angels would play teams in the National League West and American League West.

The sides discussed expanding the postseason from 10 to 16 teams for the next two years, but it appears players will not grant that revenue-boosting lever to the owners this season.

Rosters will be expanded from 26 players to 30 or so to account for the probable cancellation of the minor league season. Teams are expected to carry taxi squads of 20 to 25 players to supplement big league rosters.

After rejecting the owners’ offer of a 72-game season at 70% of their prorated salaries June 12, players all but dared Manfred to exercise his authority to impose a regular season of about 50 games June 13, with Clark saying, “It’s time to get back to work. Tell us when and where.”

Players grew even more frustrated two days later when, in a letter to the union, MLB said it would not honor the players’ demand to announce a schedule unless the union, which believed it could pursue a grievance, waived legal claims against the league.

Both sides accused the other of negotiating in bad faith, Clark saying he was “disgusted” at a bargaining process he described as “futile,” and Manfred saying the union’s tactics “make it extremely difficult to move forward in these circumstances.”

The ill will between players and owners, Manfred added, “is just a disaster for our game, absolutely no question about it.” Amid such rancor, talks broke down.

Players had proposed regular seasons of 114 games in late May and 89 games in early June, both offers including expanded 14-team or 16-team postseasons. They rejected proposals by owners for seasons of 82, 76 and 72 games.

At the core of the impasse was the interpretation of a March 26 agreement in which players accepted a pay advance equivalent to 4% of their 2020 salaries — a total of about $170 million — and a prorated portion of regular-season pay based on the number of games played in exchange for a full year of major league service time even if the entire 2020 season was cancelled.

Joe Maddon spearheaded the opening of a community center in Hazleton, Pa., where kids of all backgrounds gather for sports and other programs.

The agreement, struck two weeks after the coronavirus outbreak shut down spring training in Arizona and Florida, also contained language committing owners and players to “discuss in good faith the economic feasibility of playing games in the absence of spectators.”

With a loss of billions of dollars from tickets, parking, food, drinks and merchandise, which owners say account for roughly 40% of a team’s overall revenues, owners pushed for a further reduction in player salaries, claiming they would lose more money by playing games without fans than by not playing at all.

Owners argued that players were obligated to renegotiate salaries for games played in fan-free ballparks. The players disagreed, refusing to negotiate on the issue of pay because they said the owners had not provided sufficient information to document their claimed losses.

The bickering between billionaires and millionaires over money, amid a backdrop of double-digit, pandemic-induced unemployment and nationwide protests against police brutality and racial injustice, did not go over well with fans.

The acrimony between the sides was clearly evident in early June when players scoffed at the owners’ last proposal and MLB deputy commissioner Dan Halem, in a letter to lead union negotiator Bruce Meyer, said the union’s “failure to act in good faith has caused enormous damage to the sport.”

Seven official proposals were exchanged — four from the league and three by the union, which preferred to play as many regular-season games as possible and preferred to extend the postseason deep into November, with playoff and World Series games potentially being played at neutral sites.

Manfred balked at November baseball because it would increase the chances of the season being interrupted by a potential second wave of the coronavirus and because MLB’s television partners — the ones that would provide $787 million in postseason broadcast revenue — want the postseason completed in October.

A grievance filed on the part of the union would add a gray cloud to already stormy skies: a 2020-21 winter in which veterans without guaranteed contracts would find little or no work available as owners look to cut costs amid steep declines in revenue; a 2021 season in which ballpark capacities could be limited because of the coronavirus; and negotiations for a new collective bargaining agreement to replace the one that expires after the 2021 season, between two sides that distrust one another now more than at any point since the 1990s.

That could lead to a lockout in 2022, which would mark the sport’s first work stoppage since the strike that forced cancellation of the 1994 playoffs and World Series and delayed the start of the 1995 season by three weeks.

“It’s absolute death for this industry to keep acting as it has been,” Cincinnati Reds pitcher Trevor Bauer tweeted Monday. “Both sides. We’re driving the bus straight off a cliff. How is this good for anyone involved? COVID-19 already presented a lose-lose-lose situation and we’ve somehow found a way to make it worse. Incredible.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.