Here’s why MLB players’ distrust in the owners could torpedo a 2020 season

If the 2020 baseball season blows up over money, the repercussions will be bad for players, bad for owners, bad for the sport.

That is no great insight. Rest assured the players know this, and so do the owners.

But, if this were just about the money, the two sides could calculate a difference and split it, and teams could be headed to spring training next week.

It is about money, yes, but it is about trust too. The players don’t trust the owners.

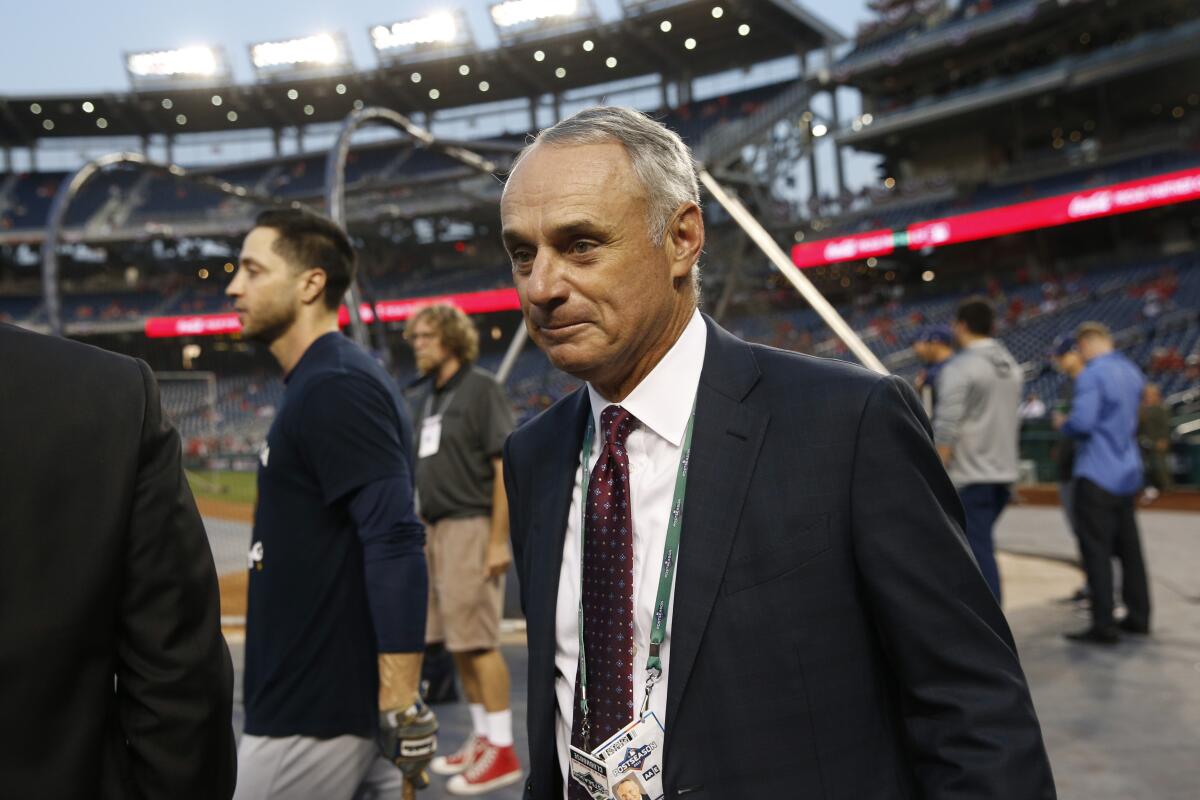

The commissioner works for the owners. They hire him, and they can fire him. Rob Manfred, the current commissioner, was promoted in 2015 to replace Bud Selig, who said he had told owners to “judge me on their asset value.”

Former Dodgers first baseman Adrián González believes players should hold the line against owners, but doesn’t believe there will be a 2020 MLB season.

The money rolled in, for owners and for players. But the unraveling of two decades of labor peace began in 2013, when Michael Weiner died of a brain tumor. He was 51.

Weiner was the executive director of the players association, and before that a longtime lawyer for the union. He and Manfred had worked on multiple deals over the years with mutual respect and trust.

Weiner’s death accelerated the ascension of Tony Clark, the former first baseman, and the first union leader who was not a labor lawyer. Clark surveyed players on their priorities in the next collective bargaining agreement, negotiated in 2016. Times were good, and players secured creature comforts: fewer night games on getaway days; more days off; better nutrition; World Series home-field advantage to the team with the best record.

The underlying assumption: Owners by and large would continue to act in what players considered good faith.

The union’s negotiating team did not foresee the degree to which owners would embrace analytics to bolster the bottom line, not just the baseball operation.

The luxury tax threshold became a de facto salary cap. The promise of big dollars in salary arbitration and bigger dollars in free agency became increasingly limited to elite players, with the rest at risk of replacement by younger, cheaper players.

While the NBA and NHL take steps to resume, MLB is arguing with its players over money. Baseball will lose a great deal if no season is played.

Not all teams played to win. Some kept their best young players in the minor leagues at the beginning of a year to delay free agency six years later. Some tanked entirely, playing overmatched youngsters for the sake of the high draft picks and low payrolls that came with a few years of losing — er, rebuilding.

Salaries remained flat, even as revenues continued to rise. In the name of efficiency, the owners cut spending on scouts, draft picks and foreign players. The owners told Congress they needed an exemption from the federal minimum-wage law or they would have to cut minor league teams, got the exemption, then set out to cut minor league teams anyway, also in the name of efficiency.

Forgive the phrase, but the owners played hardball.

Now come the hard times, when revenues no longer go only up. Attendance has declined for seven consecutive years. The rise in streaming has left teams vulnerable to a potential drop in the cable television money that fueled the revenue rush. And that was before the coronavirus outbreak that threatens to depress revenue for years.

The owners came for amateur players, with the draft next week cut from 40 rounds to five. Owners came for minor leaguers, releasing some and cutting $400-per-week stipends to others. Some owners came for scouts, and for minor league coaches, and for front-office employees.

The main concern of black people right now isn’t whether they’re standing three or six feet apart, but whether their sons, husbands, brothers and fathers will be murdered by cops.

It is embarrassing for the sport that the Kansas City Royals, in the smallest market in the American League, received enormous praise last week simply by promising to keep their staffers and minor leaguers on the payroll.

“We want to make the game better than we found it. That’s all,” Royals general manager Dayton Moore told reporters. “That’s all we’re trying to do. And we don’t deserve credit for that. That’s what we’re supposed to do.”

The owners now have come to the major leaguers, asking for financial relief instead of dictating it, because the major leaguers are unionized.

Can the owners be trusted to grow the game, the players wonder, when proposed minor league cuts mean 1,000 player jobs will be lost and dozens of communities would lose their link to a major league affiliate? Are we all in this together, the players wonder, when they are the product and yet the owners ask Mike Trout, the game’s best player, to take a pay cut of more than 75% while Manfred and his senior staff take a pay cut that averages 35%?

San Francisco Giants catcher Buster Posey, a six-time All-Star who seldom touches a controversy when he speaks, used his third and fourth tweets of the year to promote a venture capitalist’s assessment of the pay plan proposed by owners: “wanton disregard for fairness and the willingness to create the most hostile dynamic possible with their most valuable assets — the players — and using a sports-starved public as a battering ram to have their highly compensated employees look like selfish a--holes.”

Scott Boras, baseball’s most high-profile agent, is loudly pushing the players to play hardball, just as the owners do. Cincinnati Reds pitcher Trevor Bauer has told Boras to butt out, and he is not alone in that sentiment. However, it is worth noting that the well-respected Posey is not a Boras client.

Usually agents are the intermediary between players and teams. But the coronavirus lockdown has them performing other duties for anxious clients.

If the players give on salary now, would they trust the owners to give on something later? Some of the suggestions floated are laughable, at least as economic concessions by the owners. Lift the luxury tax for a couple years? Only four teams were projected to pay a tax this year, and revenues likely are going down. A universal designated hitter? Teams now prefer a roving cast of versatile hitters to a well-paid aging slugger; just two teams gave a DH enough at-bats to qualify for the batting title last season.

Manfred is a skilled labor lawyer, with decades of experience in baseball. Bruce Meyer, the lead union negotiator, was hired after the last bargaining loss to Manfred. Only time can build the trust that Weiner and Manfred had in one another.

Time is in short supply now. If they cannot make a deal, as you might have heard, the repercussions will be bad for players, bad for owners, bad for the sport.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.