Column: Pat Tillman’s sacrifice is an important reminder of what Memorial Day is all about

Memorial Day ain’t what it used to be.

It started off as a federal holiday to honor members of the military who died in battle but has absentmindedly morphed into the world’s largest backyard barbecue. Don’t take my word for it — take yours.

A recent poll commissioned by the University of Phoenix found just 43% of the respondents knew what the holiday stood for. The headline from the New York Post read “Most Americans have no clue why we celebrate Memorial Day,” which is harsh yet unfortunately accurate. Don’t trust the source? OK, well a Gallup Poll conducted in May 2000 found only 28% of Americans gave the correct answer.

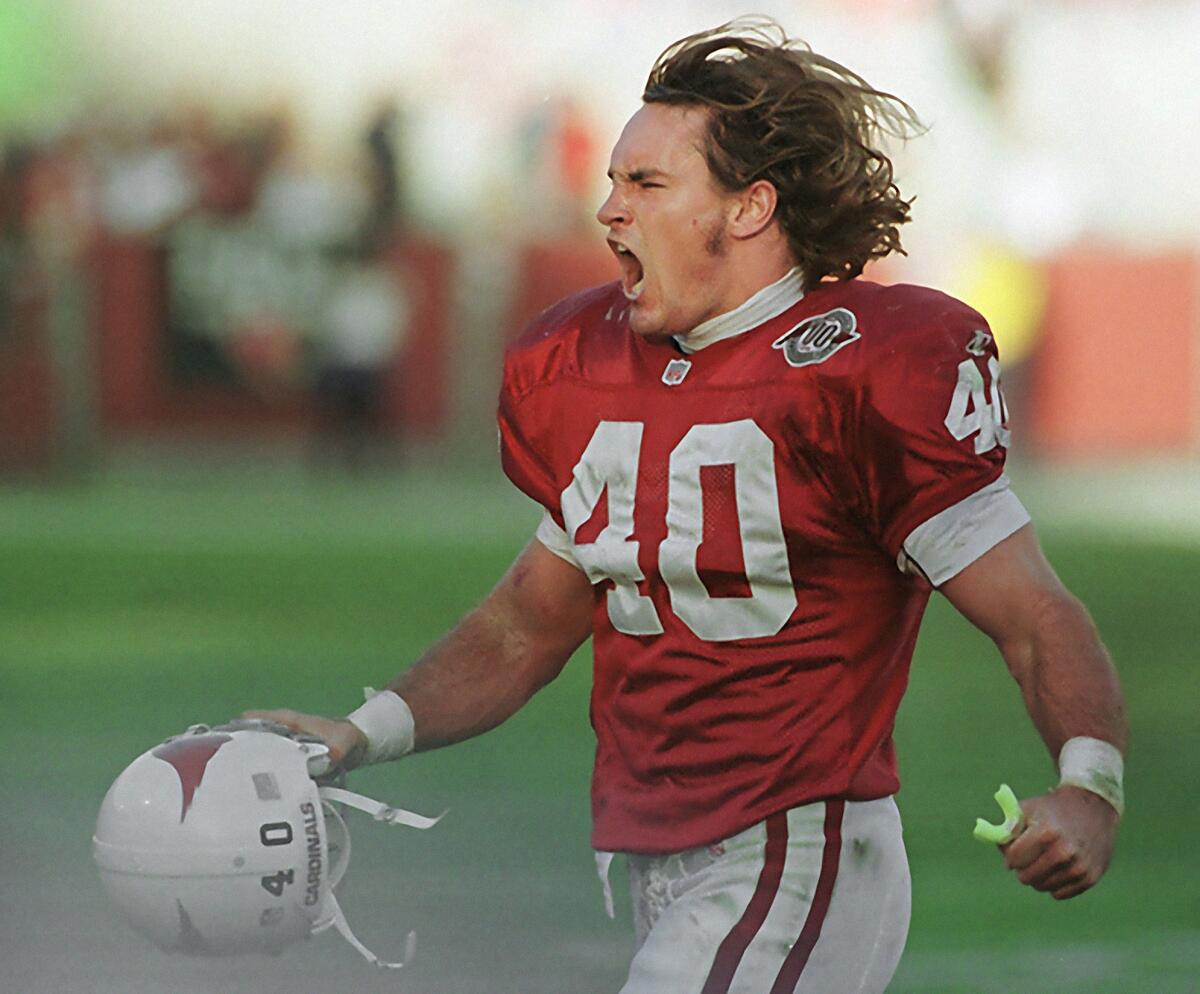

All of which brings me to Pat Tillman, the former Arizona Cardinal who famously left the NFL in May 2002 to enlist in the Army shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. Tillman and his brother Kevin, who left the Cleveland Indians farm system, both were assigned to 2nd Battalion — 75th Ranger Regiment. In July 2003 the pair were awarded the Arthur Ashe Courage Award by ESPN. On April 8, 2004, they arrived in Afghanistan. On April 22, Pat Tillman was killed by friendly fire in the province of Khost. His memorial service was broadcast on national television.

I never had the honor of meeting Tillman, but I’ve always felt compelled to remember his name and story, especially this time of year.

Not many people would walk away from a three-year, $3.6-million contract and the comforts that come with being a professional athlete to help the country. Hell, we have professional athletes today who are hesitant to play in an empty stadium to help the country. A comparison, mind you, not made to shame the players in a COVID-19 world, but rather to emphasize how special Tillman’s sacrifice was and why it is important to remember his name — even as we struggle to recall what Memorial Day is about.

The pandemic forced the 16th annual Pat Tillman Run — a fundraiser for his foundation’s program designed to support educational opportunities for service members and military families — to be held virtually. Last year some 30,000 people from around the country ran the 4.2-mile course through the streets of Tempe, finishing on the 42-yard line inside Sun Devil Stadium where he wore No. 42 as a college player. This year would-be participants were encouraged to run the 4.2 miles individually, posting images on social media using the hashtag #PatsRun.

On Memorial Day, supporters are encouraged to wear their race T-shirts in honor of Tillman and the other women and men who lost their lives in battle. And yes, we are still in battle. In fact, on March 11, the day Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert’s positive test for coronavirus started a chain reaction that shut down the sports world, two American service members were killed in rocket attack in northern Iraq. That attack brought the number of American servicemen killed in Iraq to four in four days.

This is why we have Memorial Day.

Occasionally when I walk past his statue at State Farm Stadium in Glendale, Ariz., I wonder, given what we now know, if Tillman would make the same choices. Jon Krakauer’s book “Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman” raises some doubts, given some passages about his disillusionment with the mission and President Bush’s doctrine on terror. But then there are passages about him being focused on things beyond politics, feeling small as an athlete in the larger picture, and his desire to fulfill his commitment.

In December 2003, Tillman’s agent, Frank Bauer, was contacted by Bob Ferguson, who, as general manager of the Arizona Cardinals, had played a key role in bringing Pat to the Cardinals and launching his professional football career. Ferguson, who had moved on to become general manager of the Seattle Seahawks, told Bauer that Seattle was very eager to have Tillman on the Seahawks’ roster when the football season got under way in the fall of 2004. According to Bauer, when he explained that Pat wasn’t due to be released from the Army until the summer of 2005, Ferguson assured him, “We’ve checked into it. He’s already served in a war. He can get out of the service. Just file his discharge papers. We’d love to have him here in the Seattle locker room.”

Tillman replied that he was flattered by the interest, but he wouldn’t consider leaving the Army before his contract was completed. “I enlisted for three years,” he explained to Bauer. “I owe them three years. I’m not going to go back on my word. I’m going to stay in the Army.” Bauer leaned on him to reconsider, but got nowhere.

The day the Tillman brothers enlisted, the Detroit Red Wings defeated the Colorado Avalanche to advance to the Stanley Cup Final and the New Jersey Nets beat the Boston Celtics to reach the NBA Finals for the first time in franchise history.

Sports still was happening. Life still was going on.

This is what makes Tillman’s story so singular and important to remember.

Not the military’s well-documented attempts to turn his accidental death into a heroic one and certainly not the version in which the NFL is positioned as some sort of epicenter for patriotism, as if the military didn’t pay the league millions to appear patriotic. Tillman’s story is as heartbreaking as it is inspiring. It is full of courage and sacrifice and taunts of what-if scenarios, like so many who died in service before him and after. It is the type of story Memorial Day was designed to honor.

Designed for us to remember.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.