Roger Goodell eating M&Ms and doing TikTok dances? NFL draft was nuts and we loved it

The NFL had just completed three days of public discomfort, living through the type of angst a quarterback might feel while trying to operate behind a patch-work line and without a top running back or sure-handed receiver.

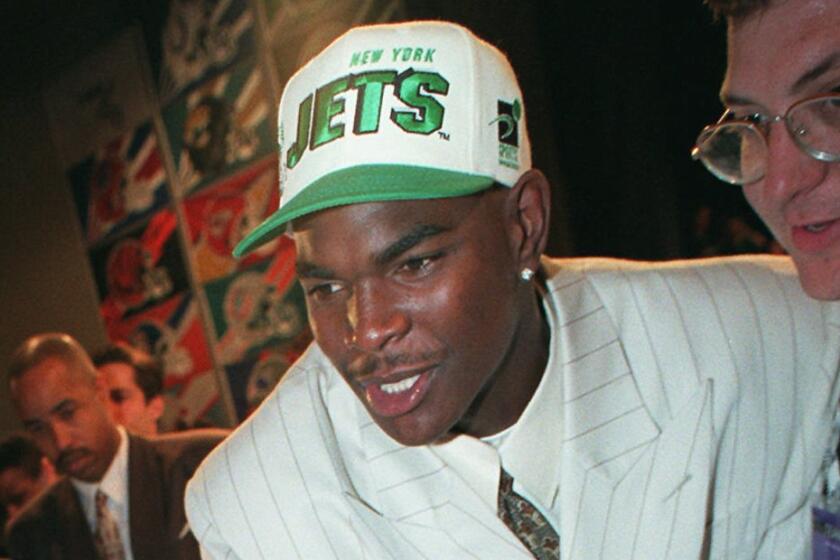

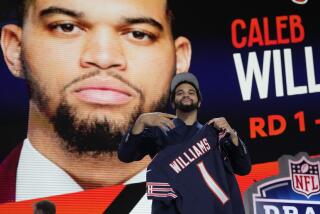

The league’s annual draft was supposed to be a polished extravaganza, and this year the plan was to ferry top players across the fountains of the Bellagio Hotel in Las Vegas as part of the red-carpet introduction, with commissioner Roger Goodell, typically dapper in one of his designer suits, on an outdoor stage adjacent to Caesars Palace.

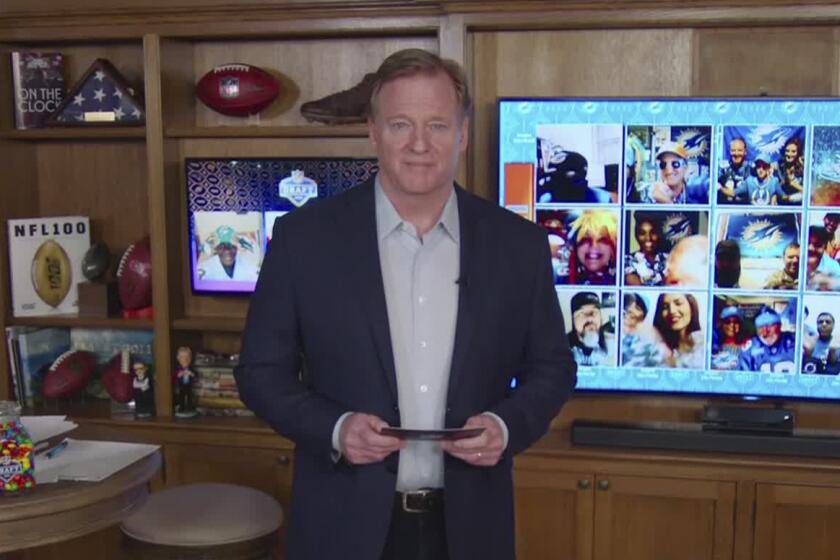

Instead, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Goodell read off each pick’s name — stumbling over a few, despite practice — from the basement of his New York home, his attire ever-more casual as the rounds rolled along, from sports coat to sweater to quarter-zip to T-shirt until he finally plopped into his favorite leather recliner and ate handfuls of M&Ms.

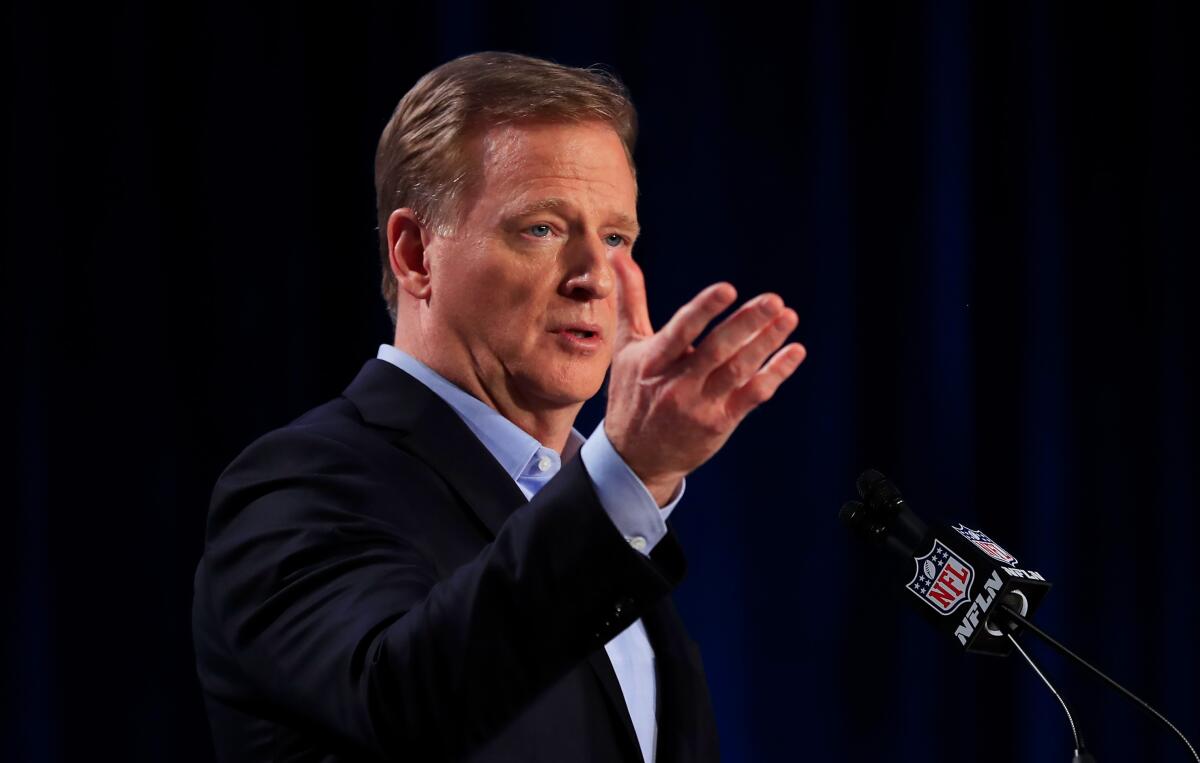

“I’m terrible at it,” he said Sunday of his debut as a show host. “It’s not my thing. I’m out of my element there.”

For the sports world, the broadcast offered a glimpse into what might be, short term or long, a new normal. The games and broadcasts, when the action resumes, might not at all look like what fans have come to expect.

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell spoke exclusively to Los Angeles Times writer Sam Farmer on Sunday, a day after the league conducted its first virtual draft.

If the NBA and NHL relaunch, the arenas are likely to be closed to fans. Baseball, if it starts up, probably will be played in near-empty stadiums. League and television executives might be advised to consider the courts and fields more like giant production sets, the broadcasts seeking ingenious ways to account for what’s missing in the sound and energy usually provided by spectators.

The NFL draft wasn’t a game, but it was the first prime-time broadcast of a major sports event since the professional leagues shut down about six weeks ago, and it was a study in ingenuity. Lacking a stage or a studio, it cut from Goodell’s basement to the homes of the selected players, with outtakes to the workstations of several team executives and coaches.

Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones checked in from his $250-million yacht. Arizona Cardinals coach Kliff Kingsbury lounged in the living room of his Paradise Valley home, a sprawling place so chic and modern it resembled the lobby of a luxury hotel. Dave Gettleman, general manager of the New York Giants, sat in front of a computer monitor in a nondescript room with a protective mask pulled over his face.

The final product had a slightly rough-hewn quality that may have only heightened its appeal. All seven rounds were carried by ABC, ESPN and the NFL Network over the three days, with more than 55 million people watching. An audience of 15.6 million watched Thursday night’s opening round, an increase of 37% from last year.

Speaking with The Times exclusively for about 45 minutes the day after the draft’s conclusion, Goodell acknowledged the broadcast benefited from timing — it was the only sports event going — and said he hoped it offered fans a pleasant diversion.

Which school has the most No. 1 NFL draft picks of all-time? This is where the rivalry between USC and Notre Dame flares up once again.

“As much stress and sadness and difficulty that our country is going through, I think the draft came at a time to help bring hope back, inspiration, and a look to the future,” he said. “It brought us together around something that was vital — not that the draft is vital, but that feeling of coming together around something is.”

Goodell said many people advised him against sticking with the draft’s original April dates believing the league could come across as tone deaf to the world’s suffering. There were also complaints from some teams that they were handcuffed by rules denying use of their facilities or the ability to bring players in for in-person visits.

“I listened to every voice — the voices I agreed with, the voices I didn’t agree with, the people who know nothing about a draft,” Goodell said. “The important thing is not to put your head down and be stubborn. But you do have to be relentless.”

As the NFL scrambled to assemble “tech kits” and send them to prospects so that video could be streamed from their homes, some people braced for what they thought might be a prime-time fiasco.

What actually developed could form a guide for other sports to follow — should they be willing to go with only a basic blueprint. So much of it was spontaneous: Goodell reaching toward his TV screen to give just-drafted players hugs and high-fives. Goodell doing a TikTok dance with Alabama receiver Jerry Jeudy.

Suddenly, he wasn’t a stuffed shirt making $40 million per year to lord over the nation’s most popular league. Goodell was Joe Fan. And he encouraged collections of fans on video to boo him the way they would at an ordinary draft. Surely some did — especially when he occasionally stumbled with his words and mispronounced names.

Goodell expected some glitches, but also a forgiving public.

“We were convinced that the general public was going to be very forgiving as it related to our technical errors, if something had a delay, or the quality of the video wasn’t good,” he said. “We were not worried about that. I told our staff before it started, ‘Things are going to go wrong. Our job is to overcome that, let it roll, pick up and carry on.’ There were a couple things that were like that, and I think people were in a very forgiving mood. They actually appreciated it even more.”

Goodell praised his staff, the hundreds of people it took to pull the production together on the fly, as well as a slew of sponsors who stepped in to offer services and technical support.

Concurrent with the broadcast, the NFL staged a Draft-A-Thon, raising more than $100 million in COVID-19 relief. Those funds will help support six national nonprofit organizations and their respective relief efforts.

“I said to our team yesterday that I’m not sure if I’ve ever been prouder of that, and I’m not sure if there’s ever been something as significant as this in our 100-year history,” Goodell said.

Oklahoma linebacker Kenneth Murray Jr. so impressed the Chargers with his presence and intensity that they traded to move up and draft him with the 23rd pick.

Personally, the event took a toll on Goodell, who by the second night appeared so exhausted that some viewers took to social media wondering whether he was ill.

“Remember,” he said, “we had just come off the labor agreement, and then pushing forward with the league year, and then having to deal personally and family-wise with the coronavirus situation and what our country is going through emotionally. And then to push our organization to go and do this, change it up. Is it right for our country? Is it the right timing? Are we doing something that might be seen as inappropriate? That weighs on you.

“I’d sleep a couple hours a night. You’re thinking about this, thinking about that. You’re writing notes. I’m getting up every 10 minutes and turning the lights on to try to write a couple things. ‘We’ve got to do this. We’ve got to do that.’ It’s just all-consuming.”

When the draft ended, Goodell headed upstairs, grabbed a bottle of whiskey and brought it back to the basement for a final spontaneous gesture.

There, he gathered with his four-member production team — all wearing masks — and proposed a toast, a virtual one, to the league executives watching via video.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.