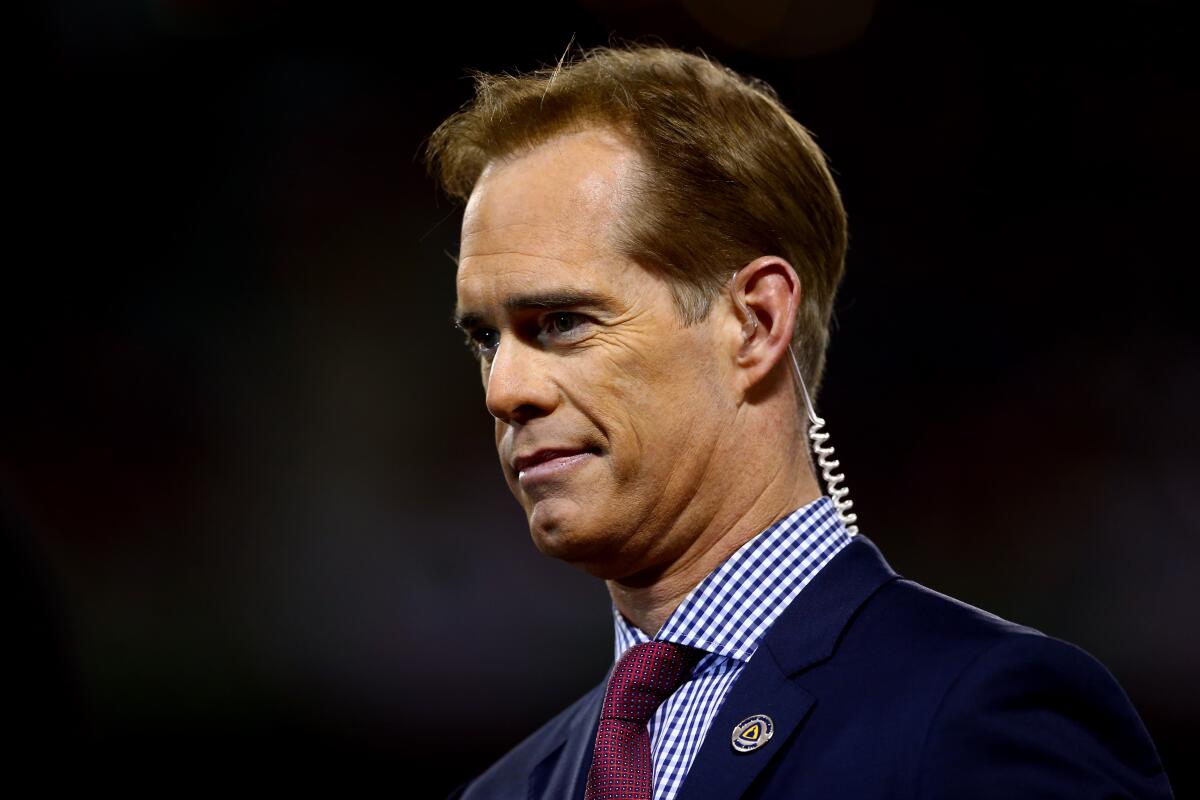

Joe Buck sees familiar tie with father, Jack, as he prepares for Super Bowl broadcast

ST. LOUIS — Joe Buck and Troy Aikman, partners in the Fox broadcast booth, will call their sixth Super Bowl together Sunday when the Kansas City Chiefs play the San Francisco 49ers in Miami. For Buck, this one is different.

It was 50 years ago that his father, legendary play-by-play man Jack Buck, called Super Bowl IV between Kansas City and Minnesota. That was the last Super Bowl involving the Chiefs, and the only one they won.

Times NFL writer Sam Farmer recently watched a restored version of Super Bowl IV with Joe Buck at the broadcaster’s home in St. Louis.

Here, in Buck’s words, are his observations about how broadcasting a Super Bowl in 2020 is so much different from when his father did so half a century ago:

The Super Bowl has never ended in a tie, but my dad’s Super Bowl began with one. It was a beautiful striped necktie, and I would wear it for the Super Bowl LIV broadcast if I could find it. It was his attire that first caught my eye last week when I sat in my home office and clicked on the link that led me to that grainy, black-and-white footage from Super Bowl IV in New Orleans precisely 50 years ago.

I refer to that as my dad’s game because it was the only Super Bowl that my late father, Jack Buck, ever called on TV, even though he did years of them on radio. It was also the last time the Kansas City Chiefs appeared in the Super Bowl, and the only one they won. So this is a full-circle game not just for Kansas City, but for my dad and me.

I noticed the necktie because its kind of funny fashion has come all the way around. So it’s taken 50 years for my dad’s style to be relevant again. When I think of him, I think of how he dressed when he was 70. He was colorblind, and he used to joke that he was one of those guys that got dressed in the dark. Things didn’t match. He needed my mom to lay out his clothes for him, and it started to trend into loud blazers. He looked like Judge Smails in “Caddyshack.” He kind of looked like Ted Knight anyway, but that’s how he dressed, kind of country-club chic, even though he didn’t belong to a country club.

Before joining the 49ers, Raheem Mostert was cut by the Eagles, Dolphins, Ravens, Browns, Jets and Bears — with some releasing him more than once.

Looking at my dad and Pat Summerall, I see two guys coming off a big night on Bourbon Street. They’re sweaty, my dad’s a little bloated, and I can tell they had fun. They weren’t stressed about doing the broadcast like I will be before this year’s Super Bowl. I’ll be tucked in my bed with eye pillows on, and his eye pillows were coasters at a bar. I’ll try to go to bed by 10 or 11, and I’ll probably lay there for an hour and a half. I’m sure he probably knocked himself out with four Manhattans and went to sleep whenever he laid down.

My dad’s wearing a monstrous headset that goes entirely over his ears — my dad and I were blessed with rather large ears — but they’re tucked in there. And the neck contraption holding up a stick microphone just doesn’t look comfortable. You’re already on national TV and trying to do a Super Bowl, and you’ve got two guys that are crammed into a tight space. They look like they’re on top of scaffolding on the roof of Tulane Stadium. It looks makeshift to me.

Troy Aikman and I will be at Hard Rock Stadium, and we’ve already scouted it out. We’ve got a green screen and all sorts of snacks laid out, a Keurig machine, and we’ll both have thick rubber mats beneath our feet because we’re standing the majority of the game. My dad and Pat look like they’re fishing off the bridge at Lake Pontchartrain down there.

If I count the monitors in front of Troy, I’ve probably got 10 screens I can look at. I’m sure they had one tiny, grainy monitor that was hooked up to the truck. The picture quality probably felt like it was from “The Flintstones,” with a pterodactyl inside carving it out of stone.

They do not have the “best seat in the house.” They’re in the “Uecker seats” up there. This Sunday, I’ll be splitting the 5 and the 0 of the 50-yard line, and I will be midway up. I’ll have the best seat in the house in a place where the get-in price is $5,000.

Also, I’m sure my dad doesn’t have a bathroom nearby. That’s my No. 1 fear and the first thing I check out before I’m doing a big game. How close is the bathroom? In this case, in Miami, it’s just outside our booth door. I think for him, he probably had to go through a “Mission Impossible”-type pulley-and-lever system to get down to the main press box so he could go to the bathroom.

Fox Sports play-by-play announcer Joe Buck shows how he prepares for a typical NFL game as he gets ready to call Super Bowl LIV between the Kansas City Chiefs and San Francisco 49ers on Feb. 2.

The commercial breaks are longer in the Super Bowl, so I don’t have to regulate my fluid intake before the game. If the bathroom is easily accessible, I don’t worry about it. But in places like Cleveland, it’s a dead sprint to get to the bathroom and back. My dad told me when I was just starting my career at 19, “Don’t ever run to a microphone, because you’re going to be out of breath, and you’re never going to catch up. You just start talking right away.” It’s virtually impossible in some stadiums to get back to the microphone in time. There, if I didn’t run, you wouldn’t hear me on first or second down. Sunday, I’m good to drink as much tea and coffee as I need. I’ll probably go through about six hot teas, two bottles of water and at least two coffees.

In the Super Bowl IV broadcast, if they were any closer to the camera, their noses would be smudging up against the lens. Troy and I have plenty of room in the booth. If my dad’s camera shot is indicative of how much room they had, there weren’t a lot of people up in the booth with them. We’ll have at least 10 people in the booth to make us look smart, including editorial consultant Steve Horn, who has been my right-hand man for 25 years.

Then you have a makeup person. I’m sure my dad and Pat just pulled up their ties and went on national TV. We’ll have makeup “artists” come in and try to defend us against high-definition television. I’m sure my dad put no thought into his outfit or looking “shiny” on air, and yet it’s perfectly fine. There’s nothing that appears out of the ordinary. It works.

There’s a beauty to the simplicity of the broadcast, a nice pace to it. It’s more of a radio commentary because both guys were coming over from radio, and people’s pictures at home were not high-definition, 65-camera shoots. Back then, you had to buttress the pictures with words to try to describe the action, because the video wasn’t what we present today.

The differences are in technology, and how crisp the pictures are in 2020, and how fuzzy it was back then. The audio is so much better now too. But overall, what Pat and my dad did back in 1970 is not a whole lot different than what Troy and I will do Sunday. They were two guys watching a game and giving their observations.

I’m seeing my dad at his best. Before age set in. Before Parkinson’s took hold. Before he went through lung cancer. Before he had diabetes and a pacemaker. Even the stresses of life. I’m seeing my dad at his peak. And I didn’t know him then. I was 8 months old, but I never knew him as that man. It’s crazy to sit in my office, turn on YouTube, and in some ways do research about the Chiefs and their Super Bowl history, and have my dad brought to life for me by people who restore this old footage. I’m so thankful because they’re presenting my dad to me like he’s broadcasting last week. It’s a lot of things that are brought to a head with one click of a mouse.

Patrick Mahomes was a high school star in Whitehouse, Texas, a town nestled in Cowboys and Texans country that has transformed into Chiefs supporters.

My dad makes a small mistake right at the beginning of the broadcast, then corrects himself. That gets me. It hits me like, “Oh my God, he makes a mistake.” These days, you try to be perfect in large part because of social media. You try to be fluid and brilliant, and never say something stupid. And in the case of a Super Bowl, you’re on the air for four hours on live TV in front of 115 million people, and you’re going to say stuff that people don’t like. You’re going to say stuff that people think is stupid. You’re going to misspeak and correct yourself.

Back then, without the pressure of social media ready to eviscerate you from people who have no idea what it feels like to be in that spot, I think they were just freewheeling and having fun. More than anything, I hear my dad and Pat relaxed. Even though national television broadcasts back then were still relatively new, and I’m sure there was an element of fear and unknown, those two still were able to be themselves.

“I wouldn’t even have realized that my dad called Super Bowl IV, but for CBS’ Jim Nantz mentioning it at the end of the AFC championship game between the Chiefs and Tennessee Titans. I’m appreciative beyond words that Jim pointed that out.”

— Joe Buck

Today, whether you’re an official or Jimmy Garoppolo, who has taken his team at 15-3 to the Super Bowl, all you hear is criticism. All you hear is, “Yeah, but he can’t do this...” I hear it too. Eventually, that stuff takes the fun out of it. I think for my dad, and certainly for Pat, they had fun. They felt little stress going into a game.

Stress is all I feel. It’s this weird pressure to try to be perfect on something that isn’t perfect, on a live event. It’s impossible to be perfect, and yet that’s the standard I hold myself to, and it takes a lot of the fun out of it.

After every game, I take two Tylenol. That’s pressure. It’s why I see a chiropractor. It’s why at the end of the game, the tension is in the back of my head at the top of my neck, because I’m standing up the entire broadcast, and I’m almost hunched over looking down over the ridiculous number of monitors we have to try to see the near sideline, to try to see the entire field. You’re almost holding your breath while you do it. I broke my neck in high school playing football, and I guarantee you whatever atrophy or disintegration I have in my spine is where the tension sits.

I remember my dad sitting at the kitchen counter, coffee steaming, cigarette lit. He would be writing the names and jersey numbers of players onto an 8-by-10-inch piece of paper he would Scotch tape to a corkboard. In the booth, a spotter hired just that day would push thumbtacks into whichever names were on the field for each play.

Using a program developed by Troy, I have a color-coded, spiral-bound spreadsheet I fill out on for each game. My spotter and stat guy, Bill Garrity and Ed Sfida, are so important to me that if they didn’t make their flights from Atlanta and Philadelphia, I might not be able to do the game.

I have had the opportunity to call some of the iconic plays in Super Bowl history, including the David Tyree helmet catch, when the New York Giants beat New England the first time. My call of that catch makes me cringe, because people said, “You weren’t over-the-top crazy on the air about how good that catch was.” The simple reason was, I couldn’t see it. It was really hard to see clearly from my angle. The last thing you want to do is to pull a groin muscle calling the Tyree catch, and then they come back and blow the whistle and say incomplete. Then you look like the idiot, and that’s all people remember.

Troy and I are on camera at the beginning of the Super Bowl broadcast. When Troy’s talking, I’m thinking: “Remember to smile so I don’t look like I’m nervous. Look back at the camera because that’s who you’re talking to.” A lot of times, I’ll picture my kids on the other side of that camera. Back when I did my first major event, in 1996 doing the Yankees’ World Series, I pictured my dad on the other end, like I was talking to him.

When Troy and I were paired in 2002, we would almost write out our on-cameras segments like we were doing a scene from “Hamlet.” Now, even though we’re going to be doing this game for over 100 million people, we really won’t talk about what we’re going to say in the “open” until we actually do it. We’ll rehearse it once, maybe twice, but we don’t have exact words. And if you don’t have exact words, then that forces you to really listen to the other person.

The other thing I try to do is try to get Troy to smile. If there’s one thing Troy has over everybody doing TV football is he’s got a great laugh. If we make a mistake in the game, we’re going to try to laugh at it. We’re going to enjoy each other’s company.

Troy will tell you that it’s just as intimidating when that red light comes on as it was for him to throw his first pass. And then you just kind of settle in. Back then, he was worried about a wet football in his first Super Bowl, at the Rose Bowl. He didn’t sleep the night before. He was deathly afraid of a wet football. We don’t have to worry about wet footballs or wet microphones, or wet anything. We’ll have a good grip on everything.

I wouldn’t even have realized that my dad called Super Bowl IV, but for CBS’ Jim Nantz mentioning it at the end of the AFC championship game between the Chiefs and Tennessee Titans. I’m appreciative beyond words that Jim pointed that out. Because for some reason over the years, it’s almost like you don’t really talk about the other network. Whether it’s CBS, NBC, ESPN ... and yet we’re all friends. Everybody knows that CBS just did the championship game, and they’re finishing up and they know that the next game is on Fox. Things have changed over the years, and that’s refreshing.

Laurent Duvernay-Tardif, an offensive lineman for the Kansas City Chiefs, is the NFL’s only active player who is also a physician. Now he gets to play in the Super Bowl against the 49ers.

I don’t know him that well, but I know him well enough to know how genuine he is. He did that because he knew it would be cool for me. I sent Jim a text saying, “That meant the world to me, but you brought my mom and my sister to tears. I’ll never be able to repay that on air.” That was a gift from a guy at another network who had nothing to gain.

If I could find that necktie my dad wore, I’d wear it. I think I’ll wear his watch this Sunday. He gave it to me one day at breakfast when we were broadcast partners on St. Louis Cardinals radio. I was 23. He said, “Let me see your watch.” I took my watch off, he took his off and said, “I want you to have this.” It was a gift from his employer for his years of hard work, and he wanted me to have it.

I think my dad would be proud Sunday and glued to the TV.

If he were alive, I’d call him after the game and ask him about the job I did. When I dialed him in October of 1996, after calling Game 6 of the World Series, he acted like he didn’t know what time the game was coming on, as if he didn’t watch any of it. Then, after a pause, he said: “It was great, Buck. It was great.” And he handed the phone to my mom.

The next day, I called home and said, “What was with Dad last night?” And she said, “He was crying so hard that he couldn’t talk.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.