Jerry Falwell Jr. wants Liberty to be the evangelical Notre Dame of college football

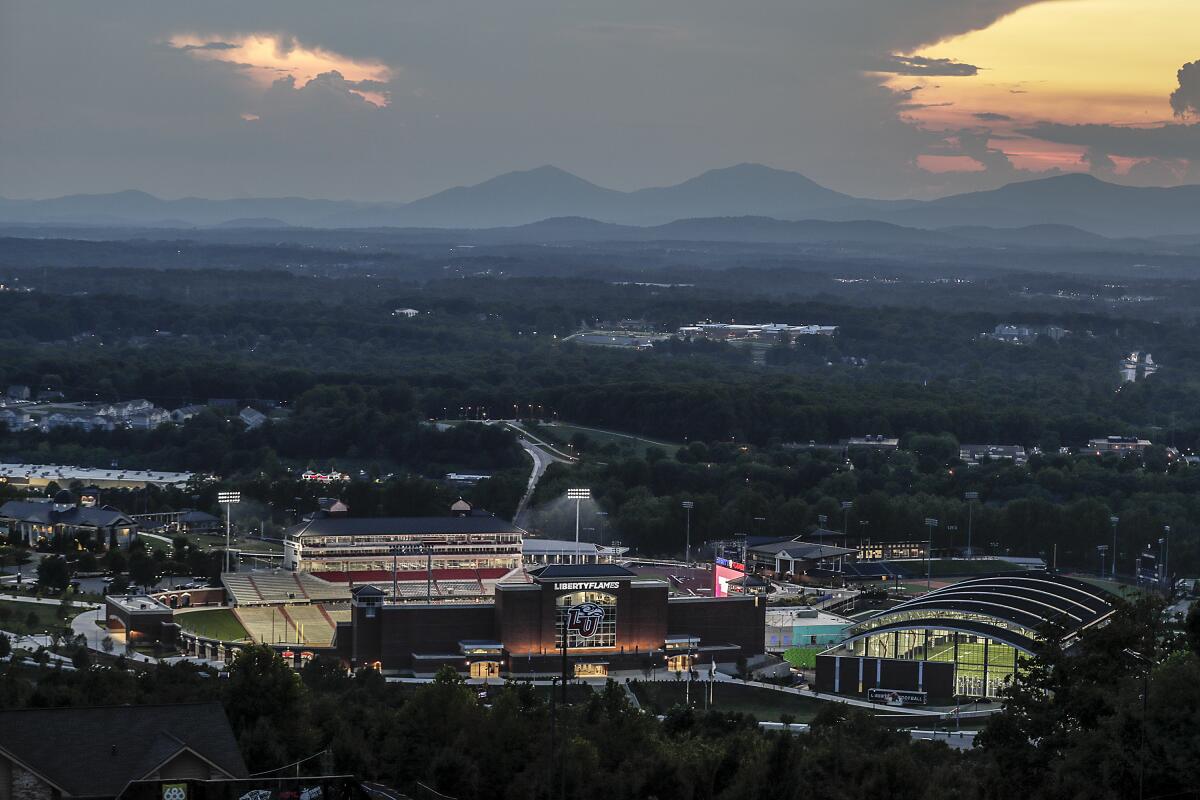

LYNCHBURG, Va. — Sundays in this sensuous stretch of the Blue Ridge Mountains come with a sense of tradition and inevitability. The hills have seen their share of tragedy, of death and rebirth, but for one family, they have forever cradled divine promises.

Jerry Falwell Sr. may be gone, but order is kept. A Falwell has had the pulpit at Thomas Road Baptist Church for more than a half-century, and the faithful file in past the red brick facade and the Jeffersonian white columns to hear the youngest son, Rev. Jonathan Falwell.

“This world is full of untruths,” he will say. “People will mock what you believe.”

The Falwells like to think vision is in their DNA, passed from their English ancestors who traversed these hills in the 1600s looking for land to own. That’s the part of the family legacy Jerry Falwell Jr., the older boy, has taken on. He reminds a visitor, even while talking passionately about sinners and his brand of Christianity, that he’s not a pastor but a businessman. He figured out how to monetize a “Christ-centered” college education, although he is known more for his hand in electing President Donald Trump — 81% of Evangelical Christians voted for Trump in 2016 — than being the president of Liberty University.

If you knew this place in 1971 when Falwell Sr. founded it as Lynchburg Baptist College, you wouldn’t believe your eyes. If you knew Liberty in 2007 when he died and left it to his oldest son to run, you probably wouldn’t either. Jerry Jr. has built $1.6 billion of infrastructure where there was once nothing but trees and grass, a campus created not from a nation’s yearning for forgiveness but rather from an online learning cash cow.

The first building that can be seen when approaching the university from the winding Richmond Highway is a towering football palace. On this “Welcome Weekend” Sunday morning in August, hundreds of students are lining up outside Williams Stadium in scorching heat to score a ticket for the season opener when the Liberty Flames host No. 22 Syracuse in the biggest home football game in school history.

Signs offering football ticket discounts cover the campus, and posters of the team’s new coach, Hugh Freeze, encourage the effort to “Rise With Us.” Clearly, there is room at Liberty for the country’s Saturday religion.

Falwell Sr. had a vision of Liberty being for Evangelical Christians what Notre Dame is for Catholics and Brigham Young is for Mormons, and the newest team in major college football is not subtle with its imagery. The Flames wear red, white and blue. Their mascot is a bald eagle.

USC running back Markese Stepp has worked hard on his receiving game as he tries dispel notions that he’s simply a ground-pounding battering ram.

With so much at stake for Liberty football, there can be no rest on the Sabbath. Inside the immaculate indoor training facility, which Jerry Jr. approved for $29 million, the players gather for a team meeting before practice.

It has been an odd week. The team hasn’t seen Freeze since he left practice more than a week before because of back pain so bad he could hardly get out of his truck when he got home. The last they heard, Freeze had developed a severe staph infection requiring emergency surgery.

“Hey guys,” Jim Nichols, Freeze’s chief of staff, says as the players settle into a meeting room, “we have a special guest with us today.”

Freeze has Skyped in from his hospital bed in Charlottesville to talk to his team for the first time since his health scare. The players are silent, looking up at a weary, grizzled figure wearing a white gown and red Liberty baseball cap.

“I just wanted to see you, men,” Freeze says. “Because it’s driving me crazy not to be with you. I miss the heck out of you.”

His players have seen him humbled before. Everyone has. In the summer of 2017 Freeze, who had taken Mississippi football to new heights, was fired when it was revealed that he had made calls to escort services across the Southeast from his university cellphone. This news painted Freeze, who had proselytized as a God-fearing and Jesus-loving man throughout his ascent in coaching, as a huckstering fraud.

But Evangelicals love a redemption tale. Freeze, who came to Lynchburg last December, had lost everything but was a proven winner, and Liberty was going to win big in football, just like everything else the Falwells set their gaze on.

With Freeze’s body attacking him from within, Jerry Jr. put the full weight of his clout into motion. He flew a specialist in from Arizona on his private jet, a story that Jerry Jr. would later connect back to his support of Trump.

Freeze does not share with his players the political twist of how their school’s president helped him, but he wants them to know something important about the place they’ve chosen for college football.

“This university loves you,” Freeze says.

::

The first day of classes is in full swing as Jerry Falwell Jr. strides into a conference room with a sprawling view of an ever-growing campus. Liberty’s grounds are lush with a different kind of green than they used to be; at least a dozen athletic capital projects have been completed since 2010, including a sparkling $32-million office for athletic administration that has few rivals across the country.

To be a worthwhile university, Jerry Falwell Sr. thought, you needed to have two elements at the front: music and athletics. Jerry Jr. motions to a university spokesman and asks him to bring over a picture frame. It contains a letter written to him in 2012 by the longtime president of Notre Dame, the late Rev. Theodore Hesburgh.

Father Hesburgh relayed the story of how Notre Dame’s 1913 football team had only 16 players when it went to play at West Point, N.Y., and upset Army 35-13.

“We won and it launched us into the big time!” Father Hesburgh wrote. “I think you are on that trajectory now, Jerry, and I just wanted to write you, to encourage you, and to wish you all the best.”

“I never met Father Hesburgh,” Jerry Jr. says. “But he knew my father.”

The televangelist Falwell Sr., despite his reputation for inflammatory pronouncements once he entered the political arena by founding the Moral Majority, was known to relate to people of all kinds. He had a friendly, round face and laughed easily.

The next generation brings more of an edge. Jerry Jr. has a salt-and-pepper beard, wears a suit with no tie and carries a casual posture at the head of the table. He answers all types of questions with no apologies, his words pouring out raw and unfiltered. But when asked about what football can do for Liberty, he defers to the man sitting next to him.

“Certainly the football program gives us a great opportunity to build our brand,” Liberty athletic director Ian McCaw says, “and convey to the world what Liberty University is all about.”

If the name Ian McCaw sounds familiar, it could be because of his role over 13 years in building the Baylor football program from the ashes into a Big 12 Conference and national contender. It could also be because of his alleged role in the Baptist university in Waco, Texas, not doing enough to protect young women during a massive sexual assault scandal.

Women students alleged in court filings and media reports that they informed Baylor of football players engaging in sexual assault, but the school said it could not act without the court’s intervention, ignoring its ability to perform Title IX investigations. The women alleged that sex was used as a way to bring talented football players to Baylor.

In 2016, highly successful and beloved coach Art Briles was suspended with intent to terminate, and President Ken Starr was demoted. McCaw then resigned, stating he felt it was in the school’s best interest to promote “unity, healing and restoration.”

Baylor, after completing its own investigation, asserted that Briles and McCaw knew of the gang rape of a woman by five football players and did not act on the information.

As the wins started to come, Baylor raised $250 million to build McLane Stadium, which opened in 2014, as the Bears climbed into the thick of the College Football Playoff race. But, looking back, McCaw does not think his athletic department put football success over protecting its students.

“I voluntarily resigned from Baylor because I didn’t believe in the narrative that this is a football problem,” McCaw says. “It was a campus-wide problem that had been going on for decades. And I felt it very unfairly scapegoated Art Briles in terms of how it was handled. I just felt I couldn’t be a part of it.”

Within months of McCaw’s resignation from Baylor, Jerry Falwell Jr. was looking for an athletic director who would know how to transition the school from Football Championship Subdivision to FBS, the top level of college football. He got a recommendation to look into McCaw, and, after doing his research on the Baylor scandal, invited McCaw to Lynchburg for an interview.

McCaw says he doesn’t recall Jerry Jr. asking him many questions about what happened at Baylor, but he soon had the job.

McCaw saw to it that the football stadium expanded from 12,000 seats to the 25,000, meeting the NCAA’s minimum requirement for FBS status. The program had no league affiliation and would play as an independent, like Notre Dame and BYU, which meant it would have to scramble to fill its schedules.

McCaw coaxed Syracuse, Virginia, Virginia Tech and North Carolina to play series that included a game or two in Lynchburg. The Orange, on Saturday, are first up.

“When it became public knowledge in July of 2017, my world crumbled. And the question started being asked: Man, is his faith real?”

— Hugh Freeze, on calls he made to escort services during his time at Ole Miss

Still, Liberty has a long way to go before becoming “big-time,” as Father Hesburgh put it in that letter. Jerry Falwell Sr. used to tell people that little Liberty would one day play a game at Notre Dame Stadium.

Jerry Jr. believed in his father’s vision. He and McCaw just needed to find the right head coach to who could bring it to life.

::

As Hugh Freeze’s journey to the big-time evolved — from the Memphis area high school coach whose real-life tale with offensive tackle Michael Oher’s adopted parents went Hollywood in “The Blind Side” to the coach at Mississippi who slayed Nick Saban’s Alabama Goliath in back-to-back years — he always knew of Liberty University.

“I just had great respect for the fact that they know who they are,” Freeze says. “They’re unashamed of who they are.”

At Mississippi, Freeze could come off like the pastor of a megachurch, but his teams routinely stockpiled top talent, and speculation was rampant around the South that the Rebels’ tactics were not above board. Freeze’s critics were vindicated when an NCAA investigation found that his assistant coaches and some boosters were providing impermissible benefits to players.

But that alone wasn’t enough for the Rebels to part with Freeze, who with back-to-back seasons ranked as high as No. 3 had elevated the program as much as any coach since the 1960s. The calls to escort services were the tipping point. In July 2017, the school let Freeze go.

Six months later, he walked onto a stage in front of 12,000 students at Liberty with a story to tell. Freeze had been put in touch with David Nasser, Liberty’s senior vice president for spiritual development, through a mutual friend. Nasser was already a fan of Freeze’s, and after speaking with him and his wife, Jill, he became convinced Liberty’s students needed to hear his message at one of their mandatory bi-weekly convocations.

Freeze felt he had apologized enough to Mississippi and the football world, but he had not owned his mistakes to the larger community of believers. With Jerry Falwell Jr. on stage watching and McCaw nearby in the audience, Freeze took the mic from Nasser and began.

“My world got rocked in 2017,” Freeze said. “And all the walls came crumbling down with what I thought was a private sin that I had struggled with. I confessed to my wife, and two of my friends, in 2016, what I thought was private and was in my rearview mirror. When it became public knowledge in July of 2017, my world crumbled. And the question started being asked: Man, is his faith real?

“I began to ask, is it possible that you can have a genuine faith and also have a season in your life that you struggle with a sin? And I started studying the scripture. And I found that is true for every single believer. Every single one of us are broken, and we have an issue. That is why we have faith.

“Today is really the first day that I can tell the faith family I’m sorry. Please forgive me.”

Someone from the crowd yelled, “I forgive you!”

“Thank you,” Freeze said. “Thank you.”

Freeze’s wife, Jill, shared the stage that day. The couple had come through a trying time with their three daughters, and she wanted the world to know where she stood on her husband’s authenticity.

“This man is the godliest man that I have ever known,” Jill said.

Her words brought Freeze to tears.

As absolution found him on that stage, Freeze couldn’t have imagined he had just completed a very public job interview. In the months that followed, McCaw kept in light touch. And after the 2018 season, when football coach Turner Gill surprised Liberty with his decision to retire, McCaw had one man at the top of his wish list.

Four days later, he announced Freeze as Liberty’s coach.

::

Ask Jerry Falwell Jr. about any reservations he had about Freeze, and he brings up Trump.

“Evangelical Christianity is all about forgiveness,” Falwell Jr. says. “It’s all about redemption. That’s what makes it different than most mainline religions. And so that’s why it was so easy for Evangelicals to accept Donald Trump, because that’s what Evangelicalism is all about. It wasn’t a big leap to make.”

Jerry Jr. is not willing to judge anyone based only on what can be gleaned directly from their actions.

“My dad, when he started the school, there were a lot of what we used to call legalistic Baptists that were really moralists more than they were Christians,” he says. “They believe that you behave a certain way, that’s what makes you a Christian.

“My dad was famous for giving students, faculty, staff, a second, third, fourth chance. People don’t realize that because his public pronouncements sounded very moralistic. But in person, he was the most forgiving human being that ever could possibly be.”

Jerry Sr. also led Evangelicals into politics. In his autobiography “Strength for the Journey,” he said he was hesitant for many years to use his spiritual influence in the political arena. Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision that federally protected a woman’s right to choose an abortion, brought him into the fray. He said he could not sit back any longer about an issue he considered morally repugnant. Falwell Sr. formed the Moral Majority and was instrumental in getting Ronald Reagan elected President in 1980.

Early in 2016, Jerry Jr. followed in his father’s footsteps, surprising many people by endorsing Trump.

After that, hiring Ian McCaw and Hugh Freeze to be the brains and the face of Liberty’s athletic department didn’t seem very controversial.

::

At a lunch event for athletic donors, the most invested Flames fans are happy to discuss what Liberty is and isn’t. The Syracuse game is two weeks away, and there is a feeling that the opponents might have the wrong impression.

“I’ve read what the Syracuse fans are saying about the game, and they’re really negative, saying we’re hateful,” says David Dolan, a 1990 Liberty graduate. “I don’t hate anybody. I mean, if you come around here, I don’t think you get the idea that we’re hating people. It’s easy to have people politicize everything, especially right now, and, you know, I’ve seen Jerry Junior out with Trump and things like that. So that’s what people are thinking.”

Dolan knows that the Falwells love to speak their mind. But, “sometimes, you could lay low,” he offers.

When Liberty hired Freeze, Dolan and his wife, Kristi, a 1989 Liberty graduate, were cautious. But then they found the video of Freeze’s convocation testimony.

“It seems like someone has to pay the price for the rest of their life for something they did,” Kristi says. “So we did our research.”

Said Dennis Fields, a fellow donor, “I think that Liberty giving coach Freeze a chance is just representative of God’s grace. And we need it every day, each and every one of us, right? We can’t throw stones, and there’s a lot of freedom in that.”

The school’s name, Liberty, was born of that purpose. But the students do have to follow certain rules in exchange for their freedom to make mistakes.

They have to attend convocation twice a week, and students who live on campus are not allowed to visit dorm rooms of the opposite sex. Curfew is midnight, 12:30 on weekends. The school has been accused multiple times of censoring the student newspaper, The Champion.

In the classrooms, learning is Christ-centered. That means that pre-med major Mason Wolk, a defensive lineman on the football team, studies a biology curriculum that does not subscribe to the theory of evolution.

For the first two decades, the school was in a constant struggle to survive. As an undergraduate at Liberty and while at law school at Virginia, Jerry Jr. took on the stress of keeping his dad’s dream alive.

“We were the only two who knew how shaky the university was financially,” he says.

The advent of the Internet saved Liberty from going belly-up to its many creditors. With Jerry Sr. and Thomas Road Baptist using the web to circulate his sermons to a wider audience, the university picked up the technology to offer online classes before most others.

In 2007, Falwell Sr. died of sudden cardiac arrhythmia in his office at Liberty at age 73. He was buried on campus. It was right around that time, Jerry Jr. says, that it became clear the university was going to turn a corner. His dad died knowing that his risks were going to pay off.

Today, Liberty has 100,000 online students, among the top enrollment figures nationally. Falwell Jr.’s goal was to have a $1-billion endowment, but he says it has already hit $2 billion.

“That took Harvard from 1636 to 1965,” he says proudly.

Now it’s football’s turn.

In a phone interview from his hospital bed, Coach Freeze says that, while of course he wants to win, he feels differently than he did during his rise at Mississippi.

“My senses are more heightened to my motives being pure about serving these kids and this university,” Freeze says. “And having compassion for the starter that can help me win games and for the walk-on that deserves it just as much. Everything I’ve gone through, it’s made me much more compassionate for people, for whatever they might be going through.”

Freeze says that he doesn’t recruit only Christian players to Liberty. Ed Gomes, the team’s director of spiritual development, says he puts players into three faith categories when they arrive: high interest, some interest, no interest. Gomes says he tries to minister by organically building deep relationships.

“People think that we’re lining our kids up against the wall and we’ve got the Bible machine guns out when kids make mistakes,” Gomes says. “What’s different here? If you make a mistake, we’re going to try to help you.”

After what Jerry Falwell Jr. did to get him the best health care possible, Freeze is even more convinced he is supposed to be here.

Jerry Jr. smiles as he tells the story.

“I was fortunate to meet a lot of the best medical professionals in the country because I supported Donald Trump in 2016,” he says.

Falwell Jr. became friends with Ben Carson, the former neurosurgeon who is Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under Trump. Through Carson, Falwell was acquainted with neurosurgeon Dr. Dilan Ellegala.

When it was clear that Freeze had a much bigger issue than back pain, Jerry Jr. sent the university plane to Arizona to pick up Dr. Ellegala and bring him to Charlottesville.

“He was within 24 hours of being in danger of losing his life,” Falwell Jr. says.

Dr. Ellegala got all of the staph from Freeze’s back. No more showed up in ensuing blood tests, and Freeze was released from the hospital Aug. 21. It is unclear if he will be healthy enough to coach from the sideline for Syracuse, but if not he’ll call the shots from the booth.

Freeze has learned many lessons since 2017, including one that resonates perfectly at his new football home.

“I used to really care about people’s opinion, writers’ opinions of me,” he says. “‘Why would you say that?’ President Falwell just does the right thing and doesn’t worry about what people think or say. Sometimes, we’re not always right, but if you get caught up in trying to please people, that is a hamster wheel life where you’re never going to catch it.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.