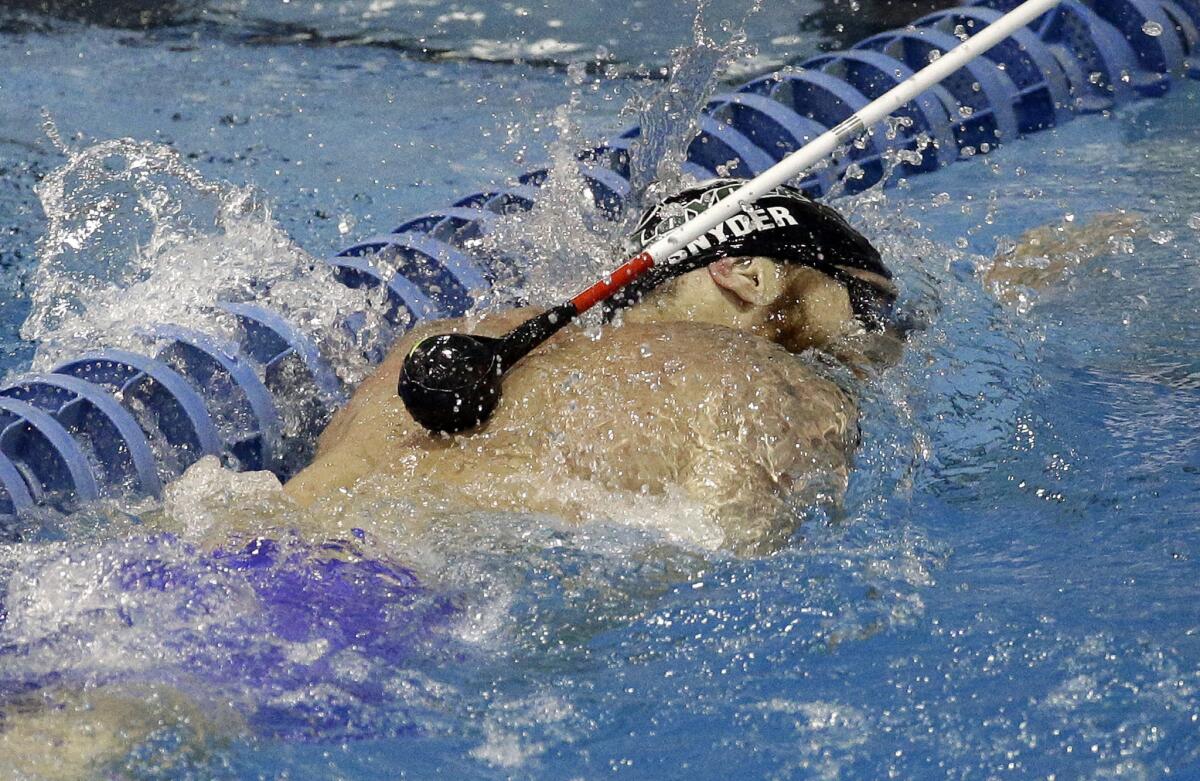

Through the darkness, blind veteran Brad Snyder becomes one of the best swimmers in the world

“I’m dead.” The thought settled on Brad Snyder in the middle of a cloud of dust and smoke raised by the blast of a homemade land mine. He lay in the fetal position on a patch of grass next to a ravine in southern Afghanistan. The Navy lieutenant couldn’t make out any blood through the haze. His arms and legs were still attached. He didn’t know anyone who survived one of these explosions with all of their limbs intact.

An instant earlier, Snyder rushed past the patrol’s Navy SEALs and Afghan commandos with a stretcher for two Afghans torn apart by a similar device. He heard a loud pop. The blast slammed him backward and bent his rifle across his body armor. The world sounded like a flatlining heart monitor.

All of this had to mean death. A short-lived wave of euphoria and sadness followed the realization. Time seemed to stop. Snyder waited for his father or grandfather — both deceased — to appear and show him the way into in the next life.

Pain jolted Snyder back to reality. His right eye didn’t work. The left one wasn’t much better. His face felt shredded. His hands hurt. A sharp ringing in his right ear welcomed him back to life.

Snyder tried to stem growing panic. He figured that his luck would run out one of these days in this scrap of Afghanistan near Kandahar choked with improvised explosive devices and rough terrain. Snyder and a fellow explosive ordinance disposal officer were in front of each patrol with metal detectors, responsible for guiding the SEAL platoon they were attached to through the region’s dangerous maze. The stress never seemed to end.

Snyder’s mind raced. Was his back broken? Did he have a brain injury? How badly was he hurt?

It actually made it easier to say, ‘OK, I know how to contend with this.’ I know what my devil is. I’ll be able to face it and figure it out.

— Brad Snyder on losing his sight

A teammate who witnessed the incident described it on the condition he not be identified because he remains on active duty and isn’t authorized to speak publicly. He followed Snyder’s voice into the cloud of smoke and dust and cut off his gear.

“I said, ‘Good news, your hands and legs are still there, but your face is [messed] up,’” the teammate recalled. “Right away he calmed down.”

Snyder, the former captain of the U.S. Naval Academy swim team, couldn’t have known that the humid morning in 2011 marked the start of a journey to compete at the Rio de Janeiro Paralympics in September. The Games open on the five-year anniversary of the explosion.

“It took my identity being stripped away,” the 32-year-old later wrote, “for me to realize who I had been all along.”

::

About a week later, Snyder awoke around 3 a.m. after four hours of surgery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

At first, he expected his vision to return. His painkiller-aided hallucinations at the hospital were so vivid — he believed he was sleeping on old motorcycle parts instead of a bed — that he didn’t realize he couldn’t see.

The blast ruptured his right eardrum and broke his right hand. Burns from the plastic jug that housed the land mine covered his right arm. Debris pockmarked his chest and arms. But his face absorbed the brunt of the damage. Doctors removed his left eye during the surgery. Not enough of the right eye remained to repair. He was blind.

Alone in the room with his mother Valarie after receiving the news, Snyder told her everything was going to be fine. He believed it too.

“The fact that my eyes won’t come back is relatively small in the grand scheme of things,” Snyder said. “It actually made it easier to say, ‘OK, I know how to contend with this.’ I know what my devil is. I’ll be able to face it and figure it out.”

::

A block party that October in Snyder’s hometown of St. Petersburg, Fla., felt like a whirl of hugs and tears and sadness. He wanted to show friends and family that blindness wasn’t going to stop him, that he was still the same person who volunteered for the demanding 13 months of EOD training because the career seemed even more unusual than becoming a SEAL, that his life wasn’t over.

“I was hungry for the opportunity to prove this idea that I’m not a victim,” Snyder said. “I wanted to show that I’m not suffering, I’m adapting. I’m struggling a little bit, but watch me. I’m going to succeed.”

Fred Lewis, the no-nonsense St. Petersburg Aquatics coach who guided his formative years in the pool, came over. Lewis always thought if he had a daughter, this was the kind of guy he wanted her to marry. Snyder wasn’t the biggest person or fastest swimmer, but his tenacity made up for it.

“Are we going to see you at practice tomorrow?” Lewis said.

The next day, Valarie Snyder drove her son to the pool. Lewis rigged foam noodles at both ends so Snyder knew when to turn. He tugged on a big scuba mask and completed four laps.

The pain and struggles faded away in the water. Finally, he could do something without help. He felt free.

::

At first, Snyder couldn’t figure out Rich Cardillo. The man in charge of military outreach for the U.S. Assn. of Blind Athletes at the time was the first person Snyder encountered who actually seemed excited that he couldn’t see. Cardillo offered the chance to return to the pool on a regular basis.

“I’m a firm believer that you don’t have to have your vision to enjoy life,” said Cardillo, who retired from the Army as a colonel in 2008 after serving 30 years. “Everything’s not lost because you can’t see.”

Snyder wanted to figure out what a career looked like for a newly blind man who spent the previous six years jumping out of airplanes, learning to disarm nuclear bombs, scuba diving, blowing things up and tromping through Iraq and Afghanistan. Swimming didn’t seem that important. On the other hand, escaping from the full-time blind rehabilitation facility in Augusta, Ga., to train three days each week wasn’t a bad deal.

Cardillo’s persistence made sense after Snyder’s first meet in February 2012 at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colo. He was the fastest fully blind swimmer in the U.S. Snyder assumed this was a mistake. It wasn’t.

Within months, Snyder moved to Baltimore to train with Loyola University swim coach Brian Loeffler and qualified for the London Paralympics.

“All of a sudden within a year I’ve got this storybook reality,” Snyder said. “I’m feeling like I’m just watching this dope Brad Snyder walk into this crazy life and I’m just watching and laughing along with everybody else. ... I look back and I think, ‘Man, how lucky was that guy?’”

The story got better. On the one-year anniversary of the blast, Snyder easily won the 400-meter freestyle for his second gold medal at the London Paralympics. After the medal ceremony, Loeffler led Snyder to his family. Valarie Snyder embraced her son. He hung the medal around her neck. The mother can’t forget her son’s words after 12 months soaked in tears.

“This is for everything we’ve been through in the last year,” Snyder said.

::

The journey hasn’t always been easy. He got lost in the family’s former home in St. Petersburg, struggled to put toothpaste on the end of a toothbrush, find food on his plate or navigate a room without banging into something.

If the worst I have to deal with is not being able to see, it’s certainly better than being dead.

— Brad Snyder

Snyder couldn’t find his way out of a Baltimore dog park during one visit. His guide dog, a German shepherd named Gizzy, briefly didn’t return to help. He felt lost. Physically, spiritually, emotionally.

“He had to learn to ask for help,” Valarie Snyder said. “That was very hard.”

Learning to wake up in darkness remains a process, but each day’s purpose is clearer. Snyder struggled to accept that swimming in the Paralympics had meaning beyond a good story to share over drinks. Working with the SEAL platoon in Afghanistan felt like the pinnacle of his existence. He didn’t look at swimming as a potential career.

That has changed.

A book he co-authored about his life comes out in September. A movie is in the works. He designed a tactile watch, works with companies like Under Armour and, when there’s time, gives motivational talks. He keeps one of the gold medals in a suitcase to bring to each speaking engagement.

“I finally accepted that what I’m doing is something valuable,” Snyder said. “My impact stems from being able to leave a positive example for the community.”

He’s also swimming faster than when he could see. That includes holding the world record in the 100-meter freestyle for swimmers who are fully blind. He could challenge the 50 freestyle world record in Rio.

A teammate or coach taps Snyder’s shoulder with a tennis ball attached to a long pole a meter before each turn. They practice the maneuver over and over, wanting it to be as fluid as a baton exchange during a track relay. He counts each stroke, so he knows when the wall is approaching.

The biggest challenge is staying straight in his lane. It brings an element of chaos to each race. He keeps his hands low to graze the lane lines with his fingers if he ventures too close. He likens it to skiing. Sometimes you hit a perfect run. Sometimes you eat it.

Every blind swimmer is going to tangle with the lane lines. What matters is who can recover and keep moving forward.

“I came back to life. I came back for a second chance,” Snyder said. “If the worst I have to deal with is not being able to see, it’s certainly better than being dead. ... I’ve gone as far down as you can possibly go. If you can reconcile your own death and still come back from that, it doesn’t get any worse. It can only get better from there.”

Twitter: @nathanfenno

ALSO

World’s top surfers are competing in Huntington Beach this weekend

Latest retesting finds 23 medalists cheated at 2008 Beijing Olympics

New-look U.S. Olympic men’s basketball team is a hit in rout of Argentina

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.