Kevin Baxter writes about soccer and hockey for the Los Angeles Times. He has covered seven World Cups, four Olympic Games, six World Series and a Super Bowl and has contributed to three Pulitzer Prize-winning series at The Times and Miami Herald. An essay he wrote in fifth grade was voted best in the class. He has a cool dog.

1

The U.S. has played host to three World Cups and each time the final has been held in Southern California, at the Rose Bowl for the 1994 men’s tournament and 1999 women’s event and in what is now Dignity Health Sports Park at the end of the hastily organized women’s competition in 2003.

That’s not likely to happen in 2026 when a 48-team men’s tournament, the largest in history, is shared by the U.S., Mexico and Canada. More than half the games, including the final, will be played in the U.S. but it’s looking more and more likely that the Cup will be raised at AT&T Stadium outside Dallas and not in Los Angeles, with New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium also pushing hard to host the final.

If that happens, say people close to the local World Cup organizing committee who are not authorized to speak publicly and requested anonymity, SoFi Stadium owner Stan Kroenke could pull his Inglewood venue out of the tournament and the World Cup could wind up bypassing Southern California entirely.

The new MLS playoff format is finding near-universal disdain from players and fans, but the league’s revenue ambitions are driving the changes.

ESPN Deportes’ John Sutcliffe recently reported that decision has already been made, but Kroenke, who also owns the NFL’s Rams and Arsenal of the English Premier League, told my colleague Sam Farmer that conversations were ongoing.

“We’re heavily involved in it, and they love our stadium,” Kroenke said. “So we’ll see where it turns out.”

FIFA officials are scheduled to make another tour of that stadium Tuesday, although, in a sign the negotiations may have turned tense, neither FIFA nor the Los Angeles World Cup host committee, are expected to comment on the meeting afterward. Both groups, which have operated with little transparency, have gone fully opaque in regard to the SoFi site visit.

And as with most things involving FIFA, what happens next will be determined by money.

Since 1994, when Alan Rothenberg, a Los Angeles attorney and civic leader, helped organize a World Cup that turned a $1.45-billion profit, much of it through deft sponsorship deals, FIFA has worked to claw back sponsorship, parking, ticket revenue and concession dollars from local organizers while also sticking them with the bill for almost all World Cup-related expenses (security, traffic control, sanitation). The financial and legal liability is so one-sided that Chicago, where the 1994 tournament opened, decided it wanted no part of this World Cup.

Los Angeles did the same before a consortium of groups, including the Galaxy, LAFC, SoFi Stadium, the Rose Bowl and the cities of Los Angeles, Inglewood and Pasadena, banded together in what appeared to be an effort to shield taxpayers from some of that risk. As a result, the Southern California bid became a private one, not a government one. Of the 10 other U.S. sites selected for the 2026 World Cup, only the San Francisco Bay Area joined L.A. in making a private bid.

However, the power and money behind the Los Angeles World Cup 2026 Host Committee rests largely with one group, Kroenke Sports & Entertainment (KSE). And this is where the plot thickens, because Kroenke has something FIFA really wants and FIFA had something Kroenke really wants.

The 3-year-old SoFi Stadium complex, which cost $5.5 billion to build, is the most expensive in the world, and its panoply of luxury boxes and tunnel entrances is exactly the kind of opulence and faux privacy FIFA royalty loves. FIFA also loves the surrounding metropolitan market, which includes Hollywood and moguls of the entertainment industry. It’s why FIFA staged its 2026 World Cup branding event at the Griffith Observatory in May.

Kroenke, meanwhile, wants the prestige of staging a World Cup game at SoFi. But not just any game. With FIFA sucking up the majority of the revenue that should rightly go to the local organizers, Kroenke stands to lose out on millions for every World Cup game played at his stadium.

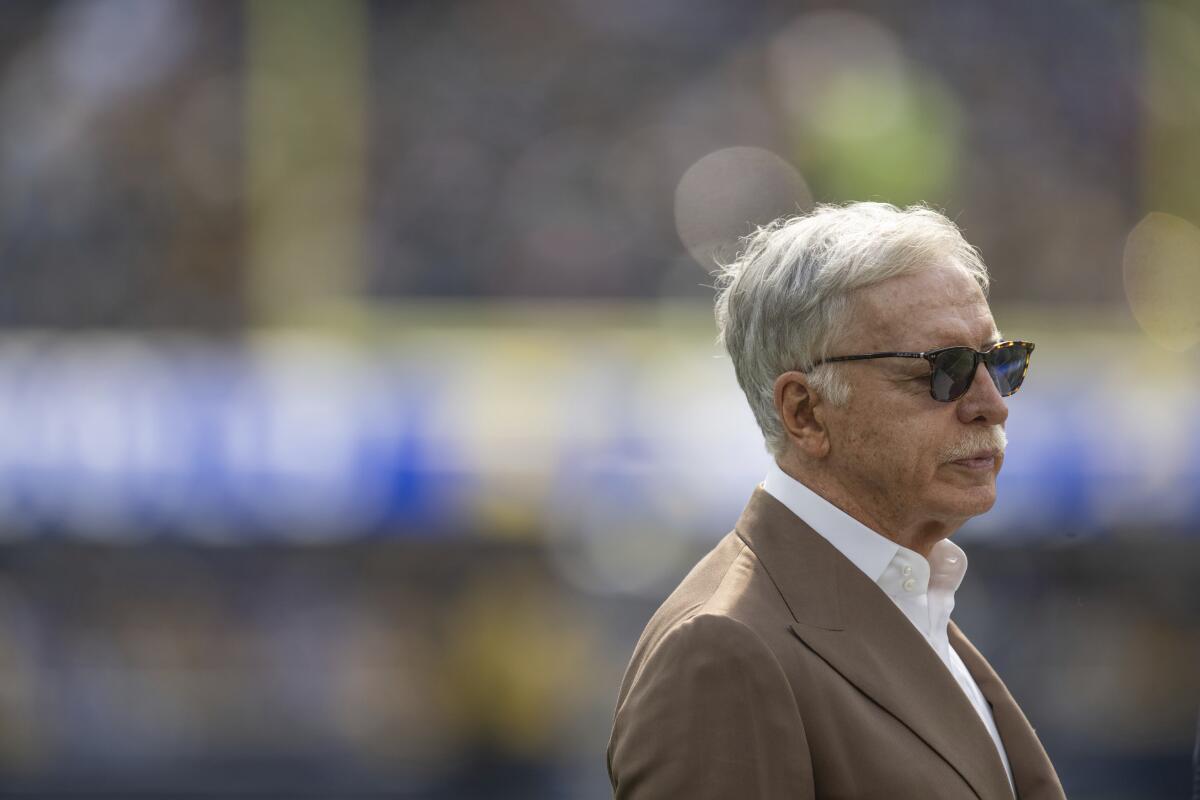

Rams owner Stan Kroenke watches players warm up before a game at SoFi Stadium.

(Kyusung Gong / Associated Press)

A group-stage game between Cameroon-Sweden, or even a quarterfinal, doesn’t have the cache to make that loss worthwhile. So Kroenke wants the final, and he apparently feels so strongly about it that he may be willing to take his stadium and go home if it doesn’t get the final, or another game of significant heft such as the U.S. national team’s opener or a semifinal.

Or perhaps the threat is simply a negotiating tool. Kroenke, no doubt, noted how FIFA president Gianni Infantino folded last fall when Qatar, on the eve of the World Cup opener, raised objections to beer sales in stadiums and the intention of team captains to wear rainbow-colored armbands in a country where alcohol consumption is heavily controlled and homosexuality is outlawed. Within hours, Infantino, in an embarrassing self-immolation, reneged on months of negotiations and promises and gave the Qataris everything they wanted.

Kroenke’s hand isn’t nearly that strong. For starters, the World Cup isn’t hours away, it’s years away. And SoFi, despite all its undeniable grandeur, isn’t up to standards for a World Cup final. AT&T Stadium, meanwhile, checks nearly every box.

For starters, Kroenke’s stadium is too small. FIFA’s own guidelines — ones the group has frequently ignored — calls for a capacity of at least 80,000 for a World Cup final and SoFi managed to accommodate just 70,048 for Super Bowl LVI and 72,628 for last January’s college football’s national championship game. In addition, the field is too narrow, and bringing it up to snuff would require Kroenke to demolish some of the ground-level suites in the corners, further reducing capacity.

Then there’s SoFi’s location on the West Coast, a nine-hour time difference from central Europe, which would require a kickoff of noon or 1 p.m. for the final to be broadcast in prime time on the continent. And FIFA loves its broadcast dollars.

Greg Vanney touted a three-year plan to lead the Galaxy back to MLS prominence when he was hired in 2021. He has yet to achieve his goal.

“One of the things we’ve looked at most hard is how the time zone works for the games around the world,” Kroenke said. “That’s a different issue. There’s a lot of speculation about this and that, what you’d have to do to the stadium.”

AT&T Stadium has none of those problems. It drew more than 103,000 for its only Super Bowl in 2011 and, while its playing surface is also too narrow for a World Cup final, there are plans to widen the field by raising it. That will wipe out some seating, but the stadium is still expected to accommodate around 90,000; the last World Cup final with a larger crowd was (wait for it) the 1994 final in Pasadena.

On their Halloween visit, FIFA officials are sure to push Kroenke to back down by pointing out the house he built is haunted by several deficiencies. KSE will answer by highlighting SoFi’s numerous bells and whistles. But when the dust settles, it’s likely that anyone living in Southern California will need a plane ticket, in addition to a game ticket, if they want to see the 2026 World Cup final in person.