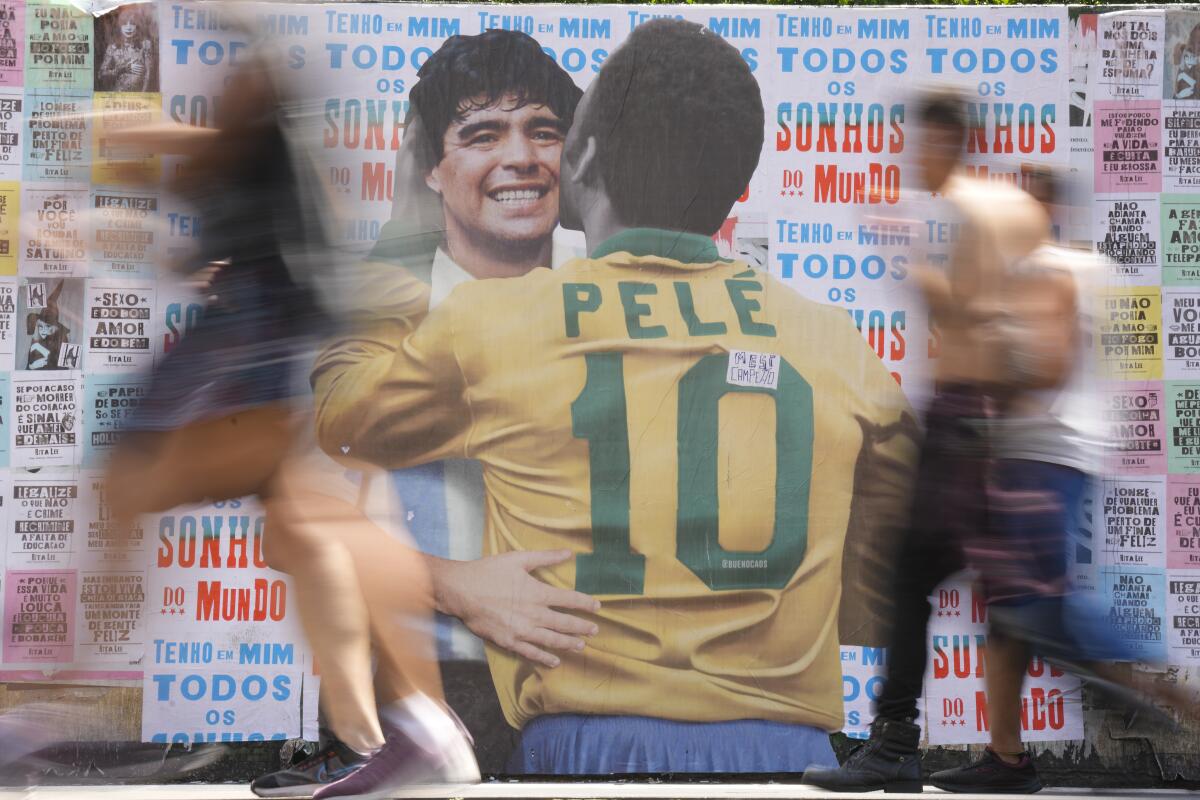

Appreciation: Pelé’s singular brilliance endured despite rivalry with Diego Maradona

Pelé was defined in the last couple of decades by what he wasn’t — namely, Diego Maradona.

Pelé was soccer’s straight-edged counter to Maradona, the outspoken cocaine addict who fraternized with Communist dictators. Pelé was the company man, Maradona was the outsider, their differences magnified by their petty long-standing quarrel over who was the better player.

To the generation whose formative years overlapped with Maradona’s prime, the Argentine’s off-the-field troubles were a byproduct of the same unpredictability that made the diminutive attacker the greatest player of his time.

In the wake of tactical evolutions that have increased coaches’ control over games, the triumph of an individual player is by definition a destruction of a system. Maradona’s behavior characterized this rebellion. Pelé’s tendency to smile and smile and smile some more was … what?

Brazilian soccer legend Pelé, who won a record three World Cup titles and helped popularize the sport in the United States in the 1970s, dies at 82.

But just because Pelé didn’t have the obvious disposition of a revolutionary didn’t mean he wasn’t one.

Maradona was more beloved, Lionel Messi has dominated superior competition, but no single player has influenced the world’s most popular sport as much as Pelé, who died Thursday of complications from cancer. “O Rei” was 82.

A winner of two World Cups — three, if you count the 1962 tournament in which he was injured in the group stage — Pelé was soccer’s first global star.

Jersey numbers used to be assigned by position and 10 was earmarked for a team’s attacking midfielder or withdrawn forward, which meant it often went to the team’s most talented player. Pelé turned the shirt into a badge of honor. Maradona wore No. 10. So has every playmaker from Michel Platini to Roberto Baggio to Messi.

The image of free-flowing Brazilian teams can be traced back to the 1970 World Cup, the first edition of the tournament that was televised in color. With their striking yellow jerseys, Pelé and his cohorts mesmerized the world with a style of play that was as effective as it was aesthetically pleasing. Many Brazilian teams since then have adopted more cynical measures, but no matter. Regardless of how ugly they play, the Brazilians are viewed by the masses as artist-athletes. Such was the imprint left by Pelé’s team.

If the 1970 squad remains the idealized vision of a Brazilian team, Pelé continues to be the archetype of the Brazilian player, as he combined explosive athleticism with high-level technique and breathtaking improvision. His legacy could be observed in the no-look passes of Ronaldinho, the flicks over defenders’ heads by Neymar.

Pelé’s impact extended beyond Brazilian borders, as some of his tricks became the signature moves by players who followed him.

Johan Cruyff’s turn? Pelé did it before him.

Maradona’s rabona? Pelé did it before him.

Cristiano Ronaldo’s chop? Pelé did it before him.

In recent years, Pelé has been excluded with greater frequency from debates about the greatest player of all time, Maradona and Messi now viewed as the only two viable contenders for the title. Detractors of Pelé point to how the version of the game he played was much slower than the one played now. They aren’t wrong.

What they neglect is to acknowledge is how much more violent the game was in Pelé’s time. About the only time Messi was subjected to the kind of fouls Pelé endured was in the final of the Copa America Centenario in 2016. A Chilean defender drew a yellow card in the 16th minute for a hard foul on Messi. The same defender was red-carded in the 28th minute after fouling Messi again. Players are now better protected.

Pelé wasn’t shielded by referees like that but nonetheless remained at the top of his sport for almost as long as Messi, 12 years separating his first World Cup triumph from his last. His style continues to be emulated to this day, even if the copycats are unaware whose moves they are stealing. He transcended the racist structures of his time to become the most famous person in the world.

Pelé was once described by a British broadcaster as “the sport’s first human billboard,” an image he reinforced by saying whatever others wanted to hear, sidestepping controversial subjects and selling anything he was paid to sell. Remember his shameless promotion of 14-year-old Freddy Adu?

None of this should be conflated with who he was as a player or the impact he made on how the game is played. On the field, there was nothing phony about him.