Soccer heartbreak is the greatest universal language

Make no mistake about it, the World Cup is about suffering.

All sports, really. The two go hand in hand. Suffering is so intertwined with sports that the verb is a favorite in headlines. You don’t just lose, you suffer defeat.

And if this is the case, then it stands to reason that no other sport is most responsible for causing suffering in this world than soccer. It is, after all, the most popular sport on the planet.

Why do we, the millions who subject themselves to the whims of a cruel sport, do it? Because we can’t imagine living without it.

“You can’t underplay how much of soccer passion comes from the joy of suffering,” said Jasmine Garsd, an Argentine American journalist at National Public Radio. She also hosts “The Last Cup/La Ultima Copa,” a podcast in English and Spanish about soccer superstar Lionel Messi’s last attempt at becoming world champion with La Albiceleste.

Garsd points to the songs you often hear from las barras, a team’s supporter groups.

“These are essentially love songs for a love interest, except it’s your team. The lyrics are like ‘I will follow you no matter what happens, and even if you fail, I will be there because I will suffer with you’!” she said.

The joy of suffering.

That’s a great way of putting it. Garsd isn’t wrong, either. No sports fan wants to take an L, but they’d be lying if they said they didn’t feel some perverse delight in experiencing defeat. It’s raw emotion. You feel … well, you feel! When José José croons about wanting to savor his suffering in “El Triste,” he may as well have been talking about fútbol.

Which brings me to the 2006 World Cup.

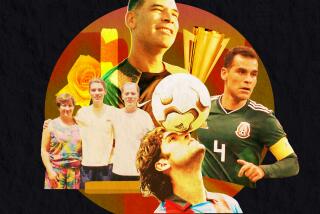

No other World Cup defeat caused me more pain than watching Mexico lose to Argentina in the round of 16. I watched that game with my father, down in South Texas. We were on top of the world after Rafael Márquez, El Kaiser de México, gave El Tri an early lead with a set play header in the sixth minute. That high would be short lived — Hernán Crespo would tie it three minutes later. The remainder of the match was excruciating. Both teams had chances to take the lead, but there was still no winner after the final whistle.

Then the inevitable happened.

In the eighth minute of extra time, Maxi Rodriguez scored one of the greatest goals I had ever seen. From outside the box, his shot arched through the outstretched hands of Mexican keeper Oswaldo Sanchez.

The goal was so impressive that it convinced this lifelong agnostic that God did exist, and that he hated México. To this day, it lives rent-free in my head. I still think about it from time to time during the quiet moments.

“Jugamos como nunca y perdimos como siempre,” my dad said of the game when I asked him about it for this story, echoing a common refrain about the Mexican men’s national team. We played like never before, and lost like always. The elusive fifth game was once again out of reach.

Years later, it now occurs to me that the reason why that match still sticks with me is because it was the last World Cup game I watched with my dad. Adulthood took me away from home, and we haven’t suffered together physically ever since.

A few days after that match, I found myself in New York City. I was en route to Paris to study abroad that summer, but made a pit stop so I could watch Germany face off against Italy in the semifinals with my German friend and college classmate Cory. The way I saw it, if my team wasn’t going to win, then I at least wanted to vicariously experience victory.

That didn’t happen. The game was scoreless after 90 minutes of play. Finally, in the waning moments of the second half of extra time, Italy scored.

“I swear to God, time slowed down,” said Cory when I asked him to relive that painful memory. By the time Italy scored again a minute later, life had already been sucked out of Lederhosen, the now-closed German bar in Greenwich Village where we watched. As we walked out dejected, someone in our group suggested grabbing a bite to eat. Without missing a beat and using an expletive, Cory angrily said he’d eat anything but pizza.

By the time I landed in Paris a few days later, France had already secured a spot in the final. A fellow classmate of mine had organized an outing to a nearby soccer stadium to watch the final with tens of thousands of Parisians. It was exciting — here I was in a country that had a real shot at winning the cup. The third time would be the charm.

Or so I thought.

After 90 minutes, there was no clear winner. We were headed to extra time yet again. And once again, whatever excitement had previously been felt quickly turned to dread. In the 110th minute, French captain Zinedine Zidane was shown a red card after headbutting Italy’s Marco Materazzi in the chest. The momentum had swung in Italy’s favor after that, and the Azurri won it in a penalty shootout.

As we exited the stadium, it hit me that never in my life had I ever felt like more of a citizen of the globe. I didn’t need to speak French to understand how everyone around me was feeling. Suffering because your soccer team lost is such a universal experience that it transcends language barriers. That particular type of heartbreak feels the same in Spanish as it does in German.

And honestly, I wouldn’t want to have it any other way.