THE PLAINS, Ohio — He dribbled an imaginary basketball around the room before taking aim at a hoop only he could see.

The 6-year-old — in his unbridled, joyous world — was an NBA legend.

“LeBron James!” he squealed.

“That’s when it hit me,” said Nathan White, Joe Burrow’s offensive coordinator in high school, recounting watching his little boy, Sam. “For the next 15 years, on playgrounds and in backyards across this country, there are going to be little kids pretending to be Joe Burrow.

“You know, we like to say Joe’s just a kid from southeast Ohio. But he’s not anymore. He’s one of the mythical people in the NFL to a child. Of all this stuff happening right now, that’s what I can’t believe.”

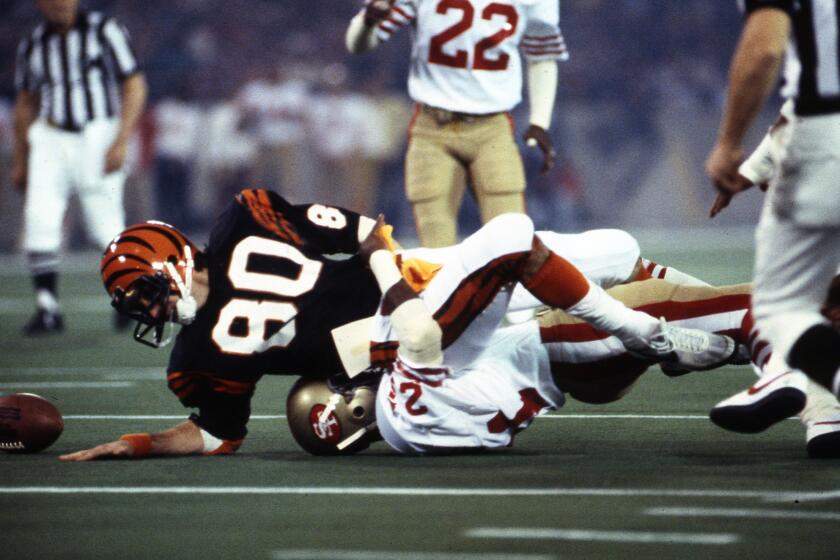

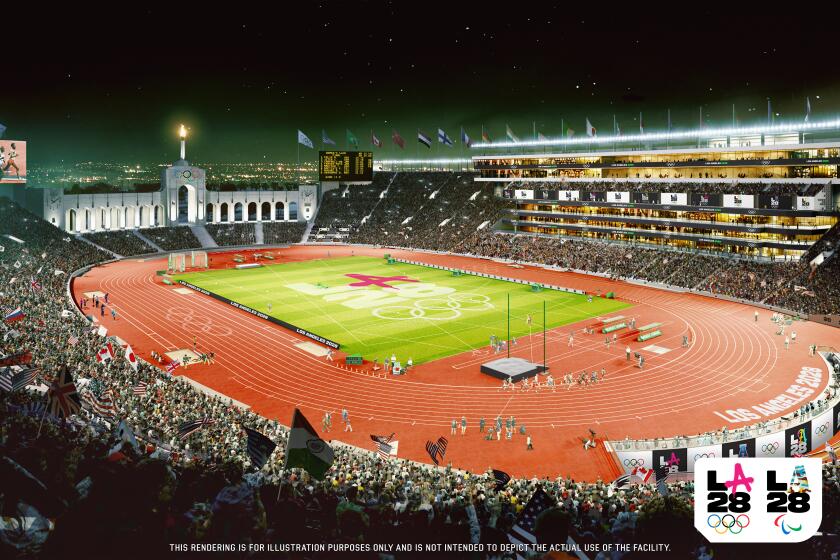

This is where the road started for Burrow, the road that makes its next stop at SoFi Stadium for Super Bowl LVI on Sunday when he leads the Cincinnati Bengals against the Rams.

The Cincinnati Bengals and their parched fans are a Super Bowl win away from finally taking a sip from the NFL’s holy grail. A look at the frenzied city.

Before he was Cincinnati’s young, ceiling-smashing quarterback, Burrow was leading Athens High football to heights unseen in the rural reaches of the Appalachian foothills.

In his three varsity seasons, he threw for 157 touchdowns and 6½ miles while the Bulldogs went 37-4 and won eight times in the playoffs. In the rest of the school’s history, there have been zero playoff wins.

In one game, his offense opened a 77-0 lead — by halftime. And that wasn’t the night Athens ran 25 plays through the first two quarters and scored touchdowns on nine of them. As a senior, Burrow was named the state’s Mr. Football.

“It felt different than a Friday night game,” said White, who was the offensive coordinator at the time and now is the school’s head coach. “It was almost like everybody was coming to watch a show, you know. ‘How fast are they going to score 50 tonight?’”

Burrow became the first Athens football player to receive a scholarship from Ohio State since the 1950s. And, even though things didn’t work with the Buckeyes, he moved on to Louisiana State and more high-scoring history.

In the 2019 season, Burrow led the Tigers to the national championship a month after winning the Heisman Trophy.

His acceptance speech for the award still echoes in these parts, despite being delivered more than two years ago and in a voice wavering and weakened by emotion.

The impressive numbers for which Burrow is responsible stretch beyond the four white lines that mark a football field. His six-minute thank you on that Saturday night in New York included 30 seconds on the less fortunate in and around his hometown.

Specific Twitter hashtags give insights into whether football fans in the United States are cheering for the Rams or the Bengals in Super Bowl LVI.

This month, the Joe Burrow Hunger Relief Fund reached $1.5 million in donations.

Now, he has the Bengals one victory from their first Super Bowl title, the 25-year-old cramming a career’s worth of achievement into something that feels like a two-minute drill.

“I guess you could say it’s all a dream,” said Burrow’s father, Jimmy. “But it would be hard to fit all this into one dream. It’d have to be multiple dreams.”

::

It is a fairly straight, roughly three-hour shot from Cincinnati, along State Route 32.

Across roads with names such as Burnt Cabin, Steam Furnace and Smoky Hollow ... past the Red Barn Convention Center, which is exactly what it sounds like it is.

Over rolling hills filled with trees as tall as they are bare and icy, and through — on this particular February afternoon — tumbling snow flurries.

The Plains, a village of roughly 3,000, sits in the heart of Athens County and next to the city of Athens, home of Ohio University.

Jimmy Burrow, a former defensive back who played for the Green Bay Packers and in the Canadian Football League before becoming a longtime coach, moved his family here after he was hired to be Ohio’s defensive coordinator in 2005.

The youngest of his three sons was entering third grade when he showed up for a peewee football camp, his hair light and his sunglasses dark.

Sam Smathers remembers his assistant coach, Heath Bullock, as they watched little Joe Burrow bound up the hill, say, “Hey, here comes ‘Joe Cool,’ your next quarterback.”

A few days after the Bengals won the AFC championship, Burrow relayed the story of how, growing up, he wanted to be a running back or wide receiver. But Smathers told him the team would be better off if he played quarterback.

“I knew he was the best we had for the position because of his knowledge, his IQ,” Smathers said. “We had other kids we could have put in there, kids who were bigger or whatever. But Joe just had a real grasp of football.”

In his garage today, Smathers has dozens of photos of the kids he has coached hanging on the walls. He also has a tiny, mostly deflated football, the last one Burrow tossed in peewees. Smathers even has what likely is the first autograph Burrow signed, on the photo of that 2005 team.

“Joey Burrow,” it reads in yellow marker, “#4.”

As Burrow was gaining his first national attention at LSU — with more and more reporters descending upon The Plains — Jimmy often would joke with Smathers, telling him, “You know this is all your fault.”

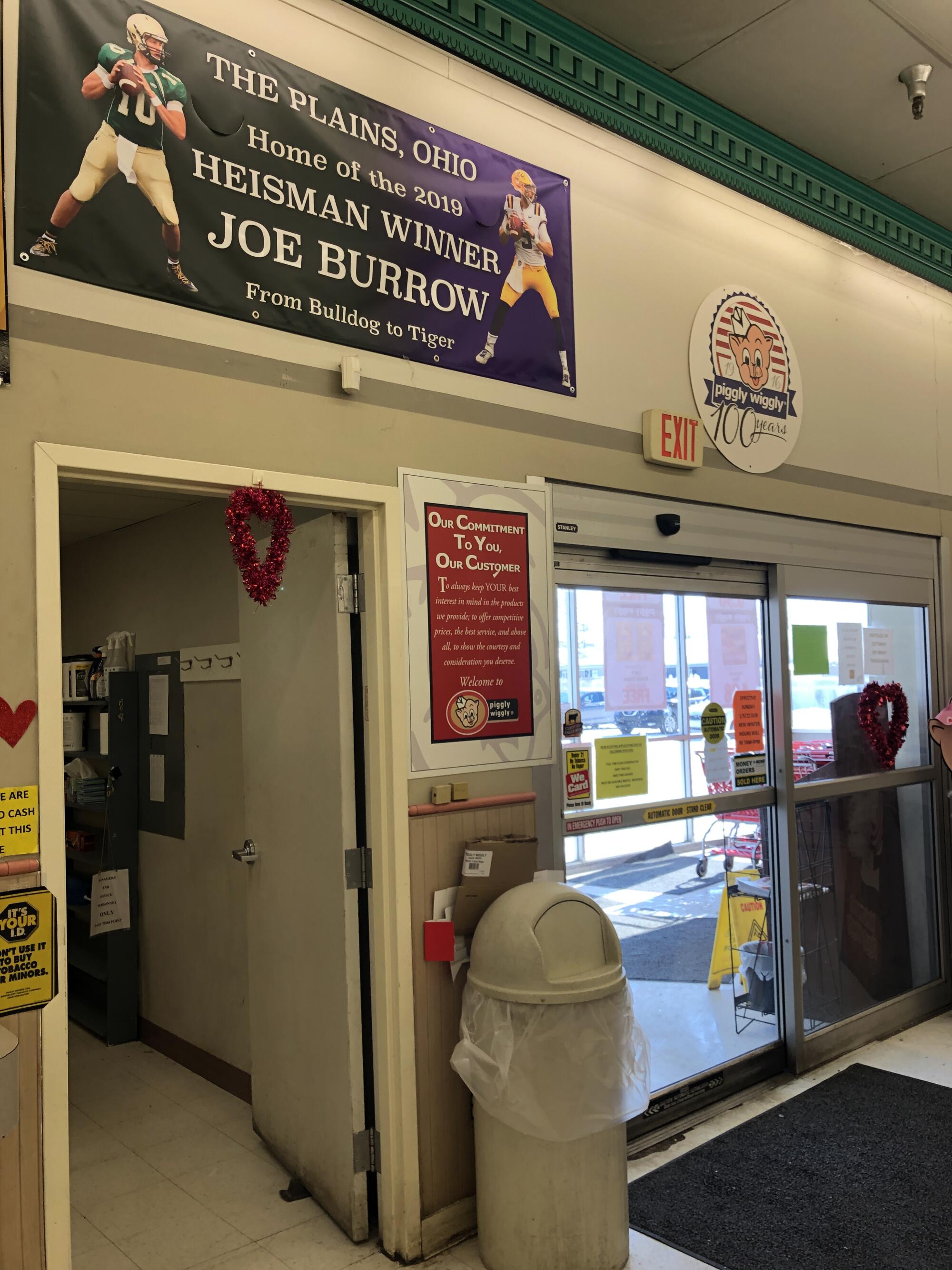

Burrow is beloved here, the signs impossible to miss. From the banner hanging in the Piggly Wiggly to The Burrow omelet on the menu of Gigi’s Country Kitchen to the LED scrolling atop Duncan Tire & Service.

They put his name on the Athens High stadium a couple years ago and posted one of his quotes — about leadership and hard work — in the school’s weight room. His Heisman is marked by a roadside sign on one end of town.

“It’s great that the world is getting to see the Joe we’ve known all along,” said Zacciah Saltzman, one of Burrow’s high school teammates. “Everything he is now is what he’s always been. What you’re seeing is just classic Joseph.”

The affiliation with Gigi’s started soon after Burrow left for LSU and talked glowingly of the café in one of his first interviews.

Before Burrow was done in Baton Rouge, the owner of Gigi’s, Travis Brand, was invited to Louisiana for a game. He arrived to a red-carpet welcome, complete with the finest available accommodations and a locker room tour.

“I had to constantly remind people, ‘I’m nobody,’” Brand said. “‘I’m just a guy who cooks cheeseburgers and omelets for a living.’ But that’s the Joe Burrow effect.”

The effect is real and it’s powerful. On game days, Burrow has become a fashion must-see, possessing a swagger that Bengals teammate Tyler Boyd called Burrow’s “own sauce.”

Entering Arrowhead Stadium before the AFC title game, Burrow wore a plush, gray jacket featuring hearts. The NFL shared video of his arrival on social media, the results going viral.

But to appreciate Burrow’s perspective on all this, consider that the jacket didn’t come from some high-end label but instead from Saltzman’s younger brother, Micah, a budding designer. Zacciah Saltzman said it cost maybe $85.

“My brother had celebrities hitting him up left and right after that,” Saltzman added, laughing. “He literally made the thing out of his bedroom.”

Burrow seems to present his fashionable moments with the slightest of winks, his style having more sense of humor than sense of purpose.

“His drip is just another part of him being comfortable with who he is and wanting to be himself,” Saltzman said. “Joe doesn’t ever do anything like that for anyone else. He just does it because he likes it.”

::

The Joe Burrow effect, Part III: A week before the Super Bowl, a carload of people pulled up at Athens High. Dan Bolington, a lifelong Bengals fan, brought his mother, son, girlfriend and others from Georgetown, about 120 miles to the west. He also brought a football.

Cris Collinsworth, who lost two Super Bowls while playing for the Bengals, thinks this season’s Cincinnati team has a chance to win it all.

They came, each dressed in an orange-and-black No. 9 jersey, to take a picture with Joe Burrow Stadium in the background. White unlocked a gate and allowed them to run routes and kick field goals on the snow-covered turf.

“A lot of people didn’t pick us this season, but I did,” Bolington said. “From the get-go, I knew the Bengals were going to make it. It was only a matter of time with Joe.”

When Cincinnati beat Kansas City for the AFC title, White and his old quarterbacks coach, Les Champlin, drove to the high school and rang the victory bell that stands next to the football field.

The sound was answered first by passing car horns and then by others drawn to the moment. Soon enough, a line had formed to take a turn at ringing the bell, too.

“There were ‘Who Deys’ coming out of back doors all around here,” White said. “It was so cool. There were literally fireworks going off from all different directions.”

Super Bowl strategy: The Bengals have more receiver targets than thin Rams secondary can handle, so a key for L.A. will be not to allow speedy wideouts to gain yards after the catch.

As big as Burrow is today, those close to him say his popularity is magnified by his understanding that there are so many things much bigger.

As he repeatedly choked back tears at the Heisman ceremony, Burrow referenced the struggles he witnessed growing up, saying, “I’m up here for all those kids in Athens … that go home to not a lot of food on the table.”

In the 24 hours after those words were uttered, 33 fundraisers were established, according to the Athens County Food Pantry.

This is an area that once boomed because of its natural resources. The coal mining and timber industries, among others, are now relatively silent, leaving behind a poverty rate of 30.2%, more than double the average in Ohio.

“The words that come to mind to me for Joe Burrow are empathic, passionate and visionary,” said Cara Dingus Brook, the president and chief executive of Foundation for Appalachian Ohio. “He has inspired others to believe that they can matter in what they give and what they do.”

After Burrow suffered a season-ending knee injury in 2020, more than 2,000 donations of $9 arrived, the support expressed as Burrow’s jersey number.

The most popular contributions lately at joeburrowfund.org have been for $31 (the number of years the Bengals went without a playoff victory until last month) and $56 (for Super Bowl LVI).

“We’ve been talking about how this is a legendary team on the field,” Dingus Brook said. “But it’s really going to be legendary for Appalachia for generations to come. The story is just beginning.”

On the morning after games in high school, Burrow and a group of teammates would go to the local Bob Evans restaurant for breakfast. At the end of the meal, Burrow would collect everyone’s change for someone in need. He often also would leave with a to-go box of food to give away.

“He’s just got a big heart,” Saltzman said. “He cares about people. Joe’s not overtly an emotional person. But you know when you sit down and talk to him that he definitely feels these things.”

The attempt to trumpet the essence of Burrow has led to an NFL-high collection of nicknames: Joe Shiesty, Joey Franchise, Joe Brrr, Joey B., Joe Cool, Joe Chill and Jackpot Joey.

He told reporters this week that he prefers to be called simply Joe, as if something so short and basic adequately could capture someone so dynamic and layered.

“You sometimes have to step back and say, ‘This is really happening?’” Jimmy said. “It’s overwhelming, but we feel great about it. We’re just blessed and fortunate to be able to experience Joe’s journey.”

Around here, they’re living the dreams, all right. With one more victory, maybe Jimmy’s son will become Super Joe, and folks in The Plains can again celebrate their most famous natural resource yet.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.