Rams’ Aaron Donald heads to hometown Pittsburgh, where star was born and he still has roots

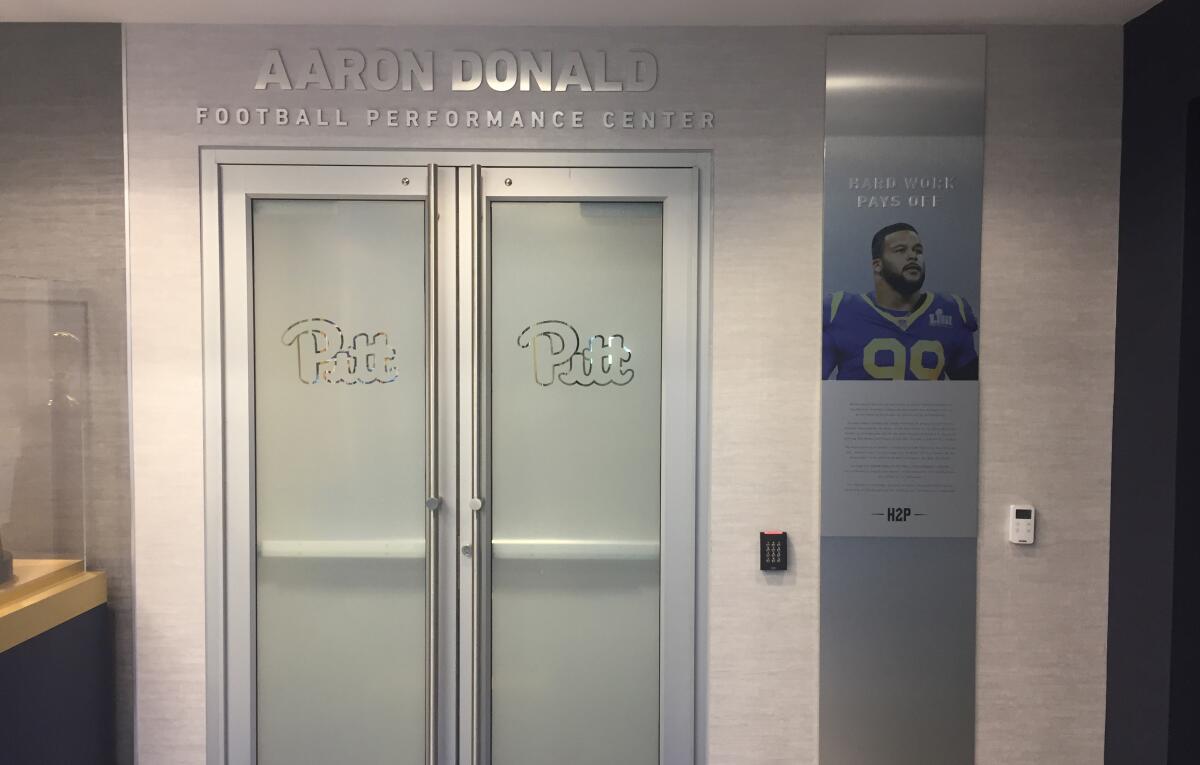

PITTSBURGH — The entryway at the gleaming facility features frosted glass doors beneath stylized lettering.

“AARON DONALD FOOTBALL PERFORMANCE CENTER” is spelled out in capital letters, flanked by a photo of its namesake. A plaque that reads “Hard Work Pays Off” accents an image of the Rams star defensive tackle, a proud product of the city and a university that keeps calling him home.

Donald, a two-time NFL defensive player of the year, signed a $135-million contract extension before last season. Eight months later, the University of Pittsburgh announced Donald had made a “seven-figure financial commitment” to the football program, the largest donation in school history by a former player.

Now his name adorns the ground floor on the Pitt side of a facility it shares with the Pittsburgh Steelers at the UPMC Rooney Sports Complex.

Donald, 28, still comes here often, to train in the weight room or neighboring indoor practice facility, to say hello to Pitt athletics administrators and staff, and to continue humbly building on an NFL career that appears likely to end with his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“His name’s on the building,” Dave Andrews, Pitt’s strength and conditioning coach, says in his weight room office, “and he’s asking for permission to work out.”

On Sunday, Donald returns to his hometown to play against his favorite team other than the Rams. Donald grew up a huge fan of the Steelers — or “Stillers” as he and proper Pittsburghers pronounce the name of their beloved six-time Super Bowl champions.

Donald might be a game-wrecking star for the opposition, but the Heinz Field crowd is expected to embrace and perhaps cheer a local kid who willed himself to stardom and wealth — and has never forgotten where he came from.

“This is a guy that’s Pittsburgh born and raised and went to Pitt and is still very active in our community, and a big-time inspiration to the young people,” Steelers coach Mike Tomlin says during a teleconference Wednesday.

“He is a beacon of everything good about this place,” says Pat Bostick, a former Pitt teammate and associate athletic director for major gifts.

In a city that features more than 400 bridges, Donald continues building his own.

His donation to Pitt football grabbed the most attention, but Donald prefers quieter acts of charity. He never turns down autograph requests from kids, invites aspiring local players to work out with him and his trainer, conducts a free football camp at his high school alma mater and launched the “AD99 Solutions Foundation” to provide opportunity for Pittsburgh youths.

“Leaving a legacy behind,” Donald says, “is huge.”

==//==

Traverse a narrow staircase from the kitchen, walk down four linoleum covered steps and make a hard right down seven wooden planks.

The descent into the musty and moist darkness ends on a red concrete floor in a 21-by-36-foot unfinished basement with cinder block walls painted white. A ceiling less than seven feet off the floor reveals exposed pipes and ducts. One light bulb is illuminated by switch. Two others must be screwed into socket with each use.

“Welcome to the Dungeon,” says Archie Donald Jr., Aaron’s father.

It’s a Monday in late September, a day after the Rams defeated the Browns at Cleveland. Archie, a former powerlifter who still looks the part, is giving a visitor a tour of the space where he introduced sons Aaron and older brother Archie III to weightlifting as a means of instilling discipline and structure.

The modest two-story house on Churchland Street is located in the Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar neighborhood in the northeast part of the city.

“Humble beginnings,” says Archie, 53.

Aaron, Archie III and older sister Akita lived here together with Archie and their mother Anita until their parents divorced when Aaron was 8. The former couple remain close friends and travel together to Aaron’s games.

Twenty-seven years ago, Archie scraped together $1,300 to buy several pieces of old used weightlifting equipment — a squat rack, pec-deck, bench press, calf-raise among others — and 1,200 pounds of weights, including a mismatched set of dumbbells. He outfitted the spiderweb-filled space with mirrors he found on the street or at junkyards.

“Best $1,300 investment of my life,” Archie says.

Aaron was in diapers when he and his brother sat on the stairs and watched their father work out. At 12, after Aaron failed to finish chores, his father enlisted him as a workout partner. Once his son saw a change in his then-chubby body, Archie reasoned, his confidence and sense of responsibility would grow.

He was right. The boys eventually worked out up to three hours a day.

“We loved it,” Archie III says, “but Aaron took it to a whole different level. ... I wanted to go play some PlayStation. He wanted to go lift some weights.”

When Aaron was a junior in high school, his father began a construction job that required an early start. That meant working out at 4:45 a.m.

“By the time of his 12th grade year, he was coming around and he was waking me up,” Archie says. “’Hey dad, I’m ready.’ He latched on to it.”

Says Aaron: “You kind of get addicted to it.”

Today, Donald is a sculpted 6 feet 1 and 280 pounds. He bought his parents homes in outer suburbs, but the family has kept the house on Churchland Street.

Clay Matthews is expected to be limited Wednesday as the Rams begin installing their game plan for the Steelers, and it’s not certain he’ll play Sunday.

Donald still works out occasionally at the Dungeon, reveling in the dust and rust.

“I was going to sell it,” Archie says of the home, “but he’s like, ‘No man. It all started at that house, Dad.’ ”

==//==

In an NFL Network preseason survey, Donald was voted the NFL’s top player by his peers.

The distinction could not have been predicted when Donald started and then abruptly quit the sport at age 5.

“But Daddy bought you these new spikes,” his mother lamented.

“You can wipe ’em off and take ’em back,” he responded.

Donald returned to the game the next year and embraced it with passion. Because of his size, he eventually was required to play against opponents three or four years older.

“He was built like a little incredible hulk when he was a little boy but he ate his way out of that,” his father says.

Donald followed his brother to suburban Penn Hills High, where he began developing into an imposing defensive presence on the field while maintaining a humble profile.

Teachers stopped Ron Graham, Penn Hills’ coach at the time, and asked if it was Aaron Donald everybody was talking about. The young man never said a word about it in class.

“Sometimes, unfortunately, high school guys get pretty cocky,” Graham says, but not Aaron Donald. “No. Not at all. Not one bit. Still the same.”

Donald’s development accelerated under the tutelage of assistant coach Demond Gibson, a former Penn Hills and Pitt defensive tackle. Donald already had an effective move, but Gibson let him use it only as a third option.

“I would teach him one move and he’d master it, and then another, and all of sudden you look up and he’s mastering all of them and doing them better than I ever did in my life,” Gibson says, laughing.

Donald also began training with DeWayne Brown, a Pittsburgh native and former college basketball player who introduced to Donald what were at the time unorthodox movement and speed drills.

“He’d be like, ‘Man, what is this? Why do I got to do this?’ ” Brown says. “But he did it.”

As a junior, Donald attracted scholarship offers from several smaller schools, including Toledo where Archie III played linebacker. But he jumped at the opportunity to sign with hometown Pitt and soon changed the perception that smaller defensive tackles could not take over games.

Donald pondered making himself available for the NFL draft after his junior season, but opted to return for a final season after performing below his standards in a bowl game. In 2013, he was a unanimous All-American selection and won four major postseason awards, including the Outland Trophy as college football’s top lineman. The Rams selected him with the 13th pick in the 2014 draft.

For the first time under Sean McVay, the Rams aren’t in the top two of the NFC West with eight games to play, but there are opportunities ahead for the 5-3 team.

Five years later, he is coming back to play where it all started.

“It’s going to be pretty cool and pretty special,” he says. “I’m going to take it all in and go out there and do what I do.

“Just play ball.”

==//==

Akita Donald has a particular memory of her younger brother.

Sometimes when he got angry, Aaron would say he was running away, packing a book bag full of snacks and leaving the house. His sister worried as he walked out.

“Ten to 15 minutes later, guess who’s back with no shoes on eating all the snacks,” Akita says, chuckling.

Donald always returned to a home where he received love, support and encouragement. And he recognized that not everyone was similarly blessed.

This year, he started the “AD99 Solutions Foundation” to provide opportunities for underprivileged kids in Pittsburgh.

“I grew up with a lot of friends that had a lot of abilities to do a lot of different things and chose different routes and it wasn’t a great outcome for them,” Donald says. “So I’m just trying to do my part.”

Akita, a professional counselor specializing in trauma-related situations, is executive director of the foundation, which aims to provide academic tutoring, athletic training and mentoring, and leadership support. In August, the non-profit selected an inaugural class of four scholarship recipients.

“One thing you find with kids that live in these crazy kinds of situations is their resilience,” she says. “You just give them a little bit of hope and a little bit of direction, they’re going to do well. They’re going to like it and want more of that.”

Donald’s willingness to reach out and embrace the community does not surprise Abner Roberts. He grew up in Pittsburgh, played college football at Duquesne and encountered Donald on the street and during training sessions with Brown.

“Pittsburgh’s a small, big city — everybody knows everybody here,” Roberts, 23, says from behind a hotel reception desk. “He’s never a hotshot. He’s humble. That’s what I like about him. He’s Pittsburgh. Blue collar.”

Donald, father to two children, is completing construction on a downtown condominium project that will serve as his home base during the offseason. He is a star playing in Los Angeles but always returns to the community where people treat him like a local.

“I don’t see myself as somebody special,” he says. “I just see myself as Aaron, the same guy I’ve been all my life.”

==//==

Sunday is Anita Goggins’ birthday — and she intends to celebrate.

Her baby boy — “He’s still the baby,” she says during an interview in a bustling coffee shop near the Pitt campus — is coming home to play against the team she supported most of her life.

As a young girl, Goggins was best friends with the daughter of a semipro football player who knew several Steelers players. So whenever L.C. Greenwood, Ernie Holmes or others showed up at the house, Goggins did too.

“I remember being a school girl with pigtails,” she says. “I sucked my thumb and I’d look up at these gigantic men.

“I didn’t know who they were. I just knew they were big — I mean huge.”

Aaron was not an overly large baby — he weighed 8 pounds 8 ounces at birth — but demonstrated physical strength shortly after his birth.

“He was literally moving his head from side to side,” Goggins says. “And he had only been here for a couple hours. So he’s always been strong and quiet.”

Now, for the first time, her son is playing a game against the Steelers in Pittsburgh, where she drove a city bus for 16 years.

Goggins often picked routes that ran through the family’s neighborhood so she could check on her kids. If she was working during her sons’ games, she chose a route that went by the field, honking the horn to let them know she was nearby.

After Donald signed his mega-deal last year, he immediately phoned his parents and told them to retire. Now Goggins helps look after eight grandchildren.

“Like I raised my kids to be best friends, my grandkids are best friends,” she says.

Goggins’ birthday celebration will last the entire weekend, culminating with Sunday’s game.

To help celebrate Donald’s return, Pitt offered the family the use of a suite, but Goggins intends to watch the game from a seat closer to the field.

“I need to be down there,” she says, “where he can hear me.”

To let his family know he can hear and see them, Donald will cross his wrists in front of his chest, the family’s longtime motivational and celebratory symbol after big plays.

“We’ve been doing it forever,” he says.

Donald knows his family will be behind him. He is not certain what kind of reception he will receive from Steelers fans.

“Hopefully, I get some love,” he says, “but hopefully they get mad at me because I’m beating up on them.

“We going to see.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.