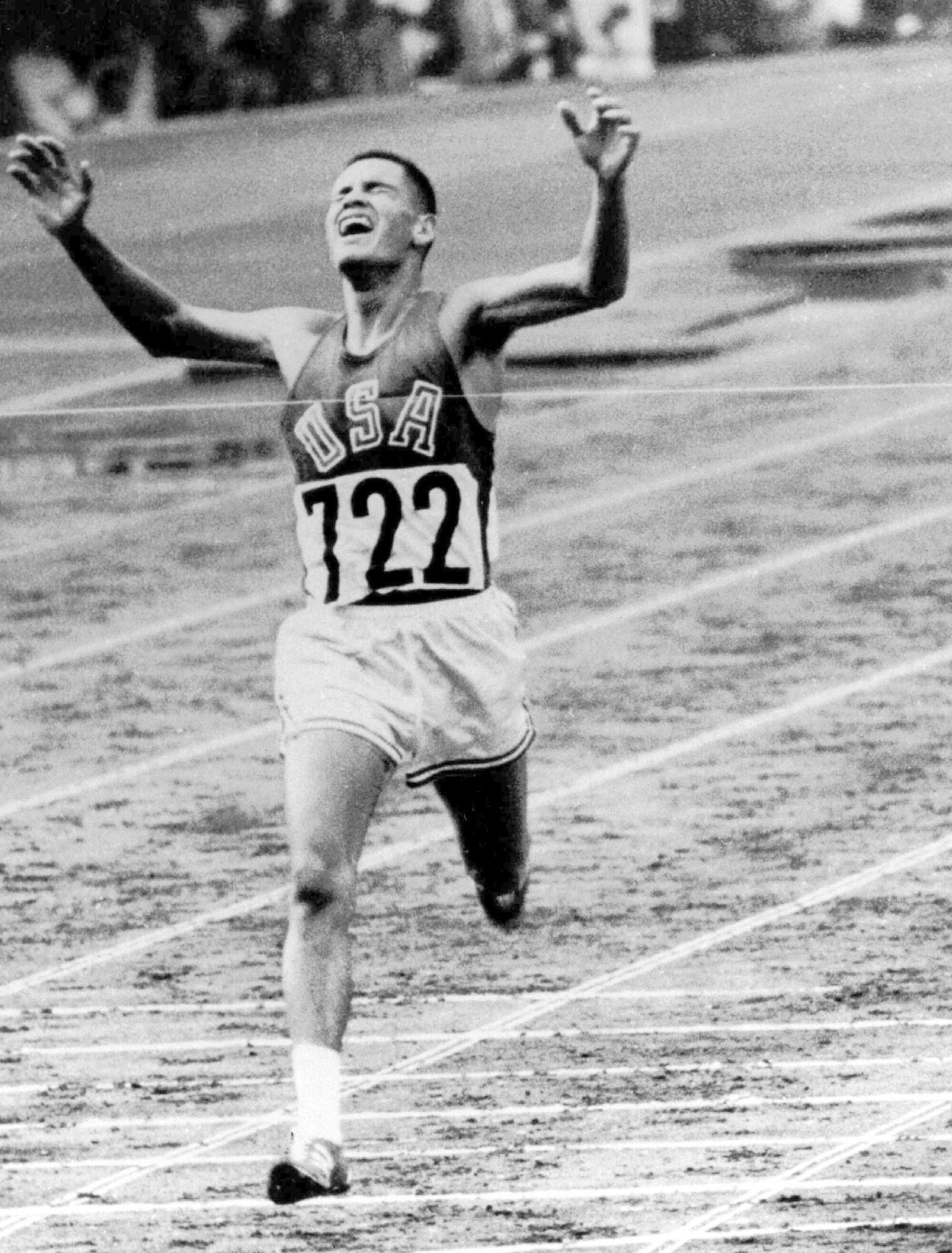

PARIS — Billy Mills is the only member of one of the most exclusive clubs in U.S. track and field history.

When he dashed away from a deep field to win the 10,000 meters on a dirt track in the 1964 Tokyo Games, Mills became the first American to win a gold medal in the longest track event in the Olympics. No one, male or female, has matched that since.

The 86-year-old Mills expects that drought to end Friday.

“We have a runner in the 10K this year who I believe has that total gift of focus and talent,” Mills said. “I am excited.”

The runner Mills was referring is Grant Fisher, the Olympic trials champion at 5,000 and 10,000 meters, the American record-holder in both events and the ninth-fastest performer in history at the longer distance with a best of 26:33.84.

No one outside East Africa has run faster.

And Mills is not alone in those thoughts. Bob Larsen, the former UCLA coach who guided Meb Keflezighi and Deena Kastor to marathon medals in 2004, said he believes Fisher has a chance at history in Paris as well — but he’s going to need a little help to make that happen.

“Grant Fisher looked stronger than ever,” Larsen said after the trials. “His stride mechanics are very efficient. He has a shot at a medal in Paris.”

But to get gold, Larsen added, Fisher will have to be lucky.

The field in Paris is the fastest ever assembled at 10,000 meters, with 15 of the 27 qualifiers having run faster than 27 minutes. Among them is world record-holder Joshua Cheptegei of Uganda (26:11.00) and Ethiopia’s Yomif Kejelcha, the world leader at 26:31.01 this year. Fisher’s best chance against a field that deep and that fast, Larsen said, is a breakaway with about a mile to go that makes it a two-man race.

“Someone would have to blister a few laps,” the Hall of Fame coach said. “If Grant could cover that move, he might have the strength to pass the guy who gambled.”

Fisher’s coach Mike Scannell, who reunited with his former high school standout 10 months ago, declined to share a race plan.

“It’s hard to predict what’s going to happen at the Olympics,” he said. “I’m not a guy that runs the race before the race actually pans out.

“I’ve just got to make sure Grant is as well prepared as Grant Fisher can be.”

Mills, who won a three-man sprint to the finish in his gold-medal race, said it’s actually a lot simpler than that. It’s more about being focused than it is about being fast.

“I have never met another U.S. Olympic 10K runner who I thought was more focused on winning as the gun was fired than I was. I have definitely met women and men with more talent than me,” said Mills, who will be on hand at Paris’ Stade de France on Friday to see Fisher run.

“Twice during my 10K I felt I may not be able to win. But immediately my mind, not my body, regained focus. The feeling was so powerful. ‘I may never be this close again. I have to do it now’.”

Mills sees that combination and mental and physical focus in Fisher who, he said, is just the second American in six decades that he thought had a chance to join him as an Olympic 10,000-meter champion. The first was Craig Virgin, who set seven national records and had the second-fastest 10,000-meter mark of all-time in 1980, but was blocked from competing in that summer’s Moscow Games by President Carter’s Olympic boycott.

“I, to this day, believe he was ready to win. He just was not allowed to line up,” Mills said.

Scannell agrees the mental part of the race is a place where American runners have often been lacking.

“It’s another facet of training that you have to address and you have to address it in practice,” he said. “I’m a coach that doesn’t leave any stone unturned when it comes to how to get the most out of somebody. So for me it’s not an option to leave that out.”

Fisher, 27, won’t be the only American in the field. Woody Kincaid, 31, who outkicked Fisher to win the last Olympic trials, then finished 14th in the Tokyo Olympics, nine places behind his U.S. teammate, will run again alongside former Newbury Park High star Nico Young, who broke the collegiate record in the 10,000 meters by 40 seconds last March, running 26:52.72 in his first attempt at the distance on the track.

That also made Young, who turned 22 last week, the third-fastest American ever in the event behind only Fisher and Galen Rupp, the silver medalist at 10,000 meters in 2012 and the only Americans besides Mills to medal in the event in the last 112 years.

That race and the Olympic Trials that followed changed Young’s thinking about the Paris Games and moved his personal Olympic timeline up four years.

“I knew that I would be competing at the trials this year but I didn’t anticipate that I would be a real contender, especially for the 10K team,” said Young, who finished behind Fisher and Kincaid, his sometimes training partner in Flagstaff, Ariz., in the trials. “I mean, I definitely was thinking of the L.A. Games as a peak of my career.

“But right now is looking fantastic.”

Peter Ueberroth and the leadership of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics proved that a mammoth event like the Games could be won as soon as the Olympic flame is lit.

For U.S. 10,000-meter runners, right now is looking better than fantastic. In fact, it’s looking better than any time since Billy Mills crossed the finish line in Tokyo 60 years ago.

“I’m hopeful that a bunch of Americans run really, really well,” Scannell said. “It’s good for the United States. It’s good for competition. And Grant is a competitor.

“If more guys can run great, that means Grant’s got to run greater. And I’m totally fine with that.”

Just as Mills will be totally fine welcoming Fisher into one of the most exclusive clubs in U.S. track and field history.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.