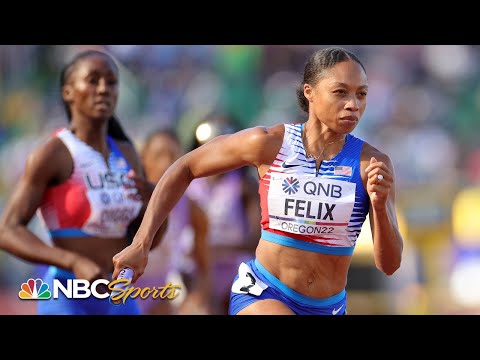

Allyson Felix goes from eating hot wings in retirement to running in 4x400 relay

EUGENE, Ore. — Allyson Felix was content to be retired.

Days after winning her record 19th medal at a track and field world championship, she was in Los Angeles indulging in what she called a cheat meal: hot wings and a root beer float at Hot Wings Cafe.

She had reason to celebrate. For two decades she had been one of the sport’s consummate performers. Her 11 Olympic medals make her the most decorated U.S. track athlete in history. With her bronze as part of a mixed 4x400-meter relay team on July 15 came a record she achieved by medaling in eight world championships over 17 years — another record.

It was a fitting place to say goodbye for an athlete who always wanted to run in a global championship in the United States, and afterward, she had spoken of being a fighter, verbally putting a bow on her career.

Then, days into retirement, the iconic sprints coach Bobby Kersee called to interrupt a meal of Felix’s favorite wings. Could she be available to run a leg on the 4x400 team in Saturday’s preliminaries?

Michael Norman earned redemption with a 400-meter crown and Sydney McLaughlin broke her own record in the 400 hurdles at the world track championships.

“Of course I was ready,” she said, adding: “Had no plans to be back here for the rest of the meet — but things happen.”

She hopped on a plane and put her retirement on hold to be a “team player,” she said. She also put herself in position to add to her record haul if the U.S., which ran the fastest qualifying time of 3 minutes 23.38 seconds, medals as expected. Felix was asked to run only in the qualifying round, not Sunday’s final — and if her 50.61-second second leg was truly her final race, then she went out in a fashion appropriate for a career notable for its speed and endurance.

Of the 31 women who raced in the United States’ heat — the Netherlands was disqualified after three legs — only two clocked a faster split than the 36-year-old Felix.

“You get back in the routine,” she said. “Bobby gave me a couple of workouts at home and you just snap right back into it. It had only been a few days.”

Leadoff runner Talitha Diggs said Felix’s return “wasn’t too big of a shock, but since she had retired and for her to come back, I was like, oh this is going to be cool.”

“To give her her last relay exchange,” Diggs said, “is pretty awesome.”

By the back straightaway, Felix had built a sizable lead, handing off to Kaylin Whitney more than a second ahead of the next-fastest team, from Britain.

“It’s kind of come full circle, literally, just kind of being in the short sprints and idolizing her,” Whitney said. “To move up to this event has just been amazing. To be able to be run alongside her as well as these other great ladies is a privilege.”

If Felix’s return drew hearty applause as soon as she touched the baton, Twanisha Terry’s lunge at the finish line ahead of Jamaica for first in the 4x100-meter relay drew roars inside Hayward Field. Jamaica had won three of the previous four world championship titles and boasted the world’s three fastest 100-meter finishers in Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, Elaine Thompson-Herah and anchor Shericka Jackson.

Jackson covered the final 100 in a blazing 9.66 seconds, yet Terry’s own leg of 9.88 won the countries’ duel because she had been given just enough of an edge after Jenna Prandini’s third leg. Prandini, racing around the corner in the stadium where she became a beloved collegiate star at Oregon, never allowed Fraser-Pryce, the 100-meter champion, to separate.

“You could have the four fastest women,” Terry said, “but if you don’t have chemistry and the baton to move through the exchange zones, then what are you doing?”

The victory primed a charged atmosphere for the men’s relay, with spectators shushed before the start over the public-address system. Running the event that has long vexed the U.S. in lane three, leadoff runner Christian Coleman ran up Noah Lyles, barely avoiding a bump. Lyles’ exchange to Elijah Hall went without incident only for Hall to tumble to the track while passing the baton to Marvin Bracy, their pass barely coming inside the legal zone.

With that hesitation, Andre De Grasse had all the space he needed. When the former USC star’s last leg was over for Canada in 8.79 seconds, he raised his arms for gold in 37.48 seconds, seven-hundredths ahead of the U.S.

De Grasse had withdrawn from the 200 meters days earlier while recovering from a bout of COVID-19. But he was ready for the relay, which meant that three of Canada’s four legs had run relays together since 2015, and all four returned from earning silver in Tokyo last year.

The U.S. struggles to manufacture such consistency because of its deep, ever-changing pool of elite sprinters — a plug-and-play selection process that had yielded uneven results. It was notable, then, that the same four U.S. men who ran the fastest qualifying time — and who said they had built strong trust during their preparatory “relay camp” — were chosen for the final, as well.

“It felt great to spoil the party for them,” De Grasse said.

It was not the U.S. disasters of 2001, 2005, 2009, 2011 and 2015 when they failed to medal at all. And it added another medal to the U.S. men’s sprinting resurgence — their eighth of these championships from the 100, 200, 400 and 4x400 relay.

But it also was not the gold-plated capper they’d so eagerly wanted, nor a successful defense of their 2019 world championship gold that resuscitated the U.S. reputation in the event.

Jake Wightman’s win at the world championships was a huge upset over Olympic champion Jakob Ingebrigtsen. And announcing the race: Wightman’s dad.

“At the end of the day we still got a medal, so you chock it up to that,” Bracy said. “We could come out [of] here with nothing but we got to tune up and we got a lot of work to do to continue to get better and win. When you sweep the [100 and 200] you expect to come out here and perform better. So it’s bittersweet.”

There is one day left in these championships, and Felix will watch Sunday’s long-relay final in Eugene before returning to Los Angeles. The advocacy that defined the latter years of her career, when she publicized the ways in which shoe sponsors cut pay for athletes while pregnant and pushed for more representation for mothers, will be a full-time role.

She’ll finish that hot wings meal now, she said.

Was this, truly, her last run?

“From what I know,” Felix said. “But what do I know?”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.