Fans banned at Olympics after Tokyo institutes a state of emergency

The Tokyo Olympics made history last year when they were postponed until this summer because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now comes another unfortunate first.

Facing a surge in coronavirus cases in the Japanese capital, the government has declared a new state of emergency beginning next week and officials confirmed Thursday what had been suspected for months — the Summer Games will proceed for the first time with no spectators allowed in the stands.

The sound of silence in empty stadiums and arenas will unarguably diminish the massive sports competition, said the International Olympic Committee, organizers and government officials in a joint statement that offered “regret for the athletes and for the spectators that this measure had to be put in place.”

“I’m a little bit heartbroken,” U.S. diver Krysta Palmer said. “I also feel heartbroken for Tokyo and the country of Japan. It’s tough for them not being able to hold a normal Olympics.”

Tokyo officials previously had suggested they would not move forward without fans but changed their minds on the same day IOC President Thomas Bach arrived in the city. Bach was expected to self-isolate in his hotel for three days and then attend meetings to discuss the issue.

Those plans were accelerated after Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga declared that a state of emergency would go into effect Monday and continue through late August, a timeline that envelops the Games, which are scheduled for July 23 through Aug. 8.

“Taking into consideration the impact of the Delta strain,” Suga told reporters, “and in order to prevent the resurgence of infections from spreading across the country, we need to step up virus prevention measures.”

Athletes seemed to understand Japan’s predicament but expressed frustration at the numerous restrictions heading into what hammer thrower Gwen Berry dubbed the “Pandemic Games.” Organizers have asked competitors to limit their stay in the country, which rules out hanging around the village and could mean skipping the opening or closing ceremony.

Triple jumper Keturah Orji tweeted: “No fans, no opening ceremony, no choosing roommates, NO ANYTHING & leave 48h after you compete.”

The U.S. men’s water polo team will experience the difference right away because it is scheduled to open play against host Japan on July 25. Marko Vavic, a Rancho Palos Verdes native who helped USC to a national championship in 2018, said an empty stadium won’t generate the sort of rush he feels from cheering fans.

“We were really excited, expecting it to be loud and rowdy,” he said, adding, “I think I definitely feed off the energy and the ruckus they cause.”

There is still a possibility fans can attend select events held outside Tokyo in prefectures where the state of emergency is not in effect. Local government authorities in those areas are expected to meet and decide on specific measures.

Organizers also said they would wait until next month to discuss a spectator policy for the Paralympics, which are scheduled to begin Aug. 24, two days after the state of emergency expires.

Japan ranks 33rd on the list of nations hit hardest by the coronavirus, with 814,315 cases and 14,865 COVID-19 deaths reported since the pandemic began, according to statistics compiled by Johns Hopkins University. But the country has been slow to react to the development of vaccines, with only about 15% of citizens fully vaccinated.

According to Kyodo News, new daily coronavirus cases in the Tokyo metropolitan area hit 896 on Thursday, with numbers approaching a mid-May peak that exceeded 1,000 a day. Suga met with several ministers from his government this week to discuss the crisis.

The Games are expected to bring about 11,000 athletes to Japan in the next few weeks. The IOC has predicted 80% of the residents of the athletes’ village will be vaccinated, but there also will be tens of thousands of officials, judges, administrators, media and others.

Still, there was uncertainty about what do with fans; even as the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic dwindled, stands at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics were crowded, sports historian Mark Dyreson of Penn State University said. Tokyo organizers previously had barred foreign spectators, then recently announced that capacity at venues would be limited to 50% with a maximum of 10,000.

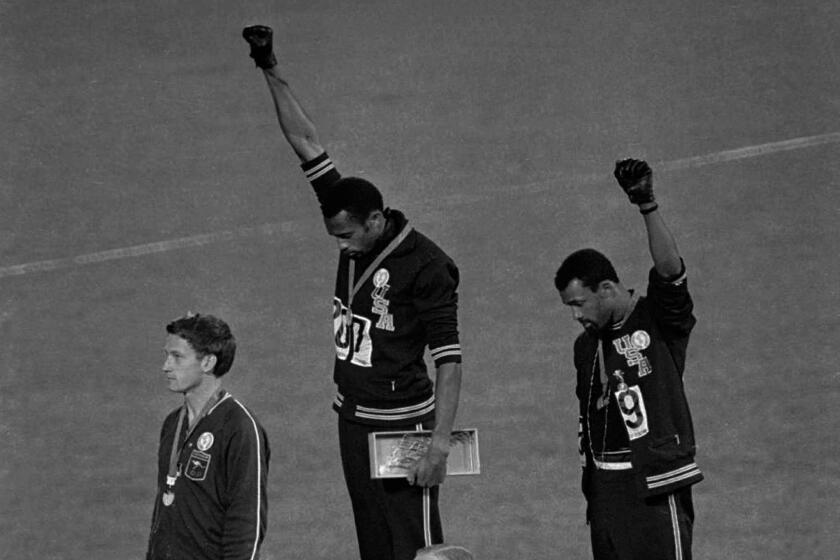

Tommie Smith, who raised his fist in protest against racism at the Olympics nearly 53 years ago, believes athletes must use their platform to start change.

The Japanese people initially had seemed enthusiastic, scooping up tickets in a series of lotteries. But public sentiment turned against the event as the pandemic persisted, with recent polls showing a majority of citizens favoring postponement or cancellation.

“It’s not too late. Cancel or postpone it,” Yukio Edano, head of an opposition party, was quoted as saying by the Associated Press.

Cancellation has met with resistance for numerous reasons. Broadcast rights account for 73% of the IOC’s $5.7 billion in quadrennial revenues. Tokyo organizers similarly need to generate money to cover costs that, by some accounts, have risen to $25 billion.

Thursday’s decision will wipe out more than $800 million the organizing committee expected to earn from ticket sales.

In the U.S., NBC has done its best to drum up interest in the Games, showing recent American trials in sports such as track, swimming and gymnastics in prime time.

With spectators banned, the network must now call upon lessons learned from months of televising sports from empty arenas and stadiums in this country. American viewers have experience watching games with artificial crowd noise and none of the usual fan shots.

Olympic athletes have relied on unique workouts and sports psychologists to overcome the shutdown robbing them of a chance to hone their competitive edge.

At a news event last week, NBC producer Rob Hyland spoke about a plan to show competitions with simultaneous video of reactions from family members back home. Athletes might also be shown interacting with family by video after their events.

“It’s a pretty elaborate plan that we’re calling ‘Friends and Family,’ ” Hyland said. “What I’m most excited about, I think what we all are, is connecting.”

As for the athletes, many have reacted with typical joy upon making the U.S. team. They have seemed willing to adjust no matter who is in the stands.

Palmer suggests that she and her diving teammates might use visualization to pretend there is a crowd. Others will narrow their focus to the field of play.

“Of course we want our family and friends there to feel the support,” U.S. soccer player Becky Sauerbrunn said recently, “but it’s all business for us.”

Times staff writer Ben Bolch contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.