When the police show up — which they sometimes do — Nyjah Huston probably looks like any other skateboarder, hanging with friends, grinding rails in the park, doing kickflips off the stairs in front of a library.

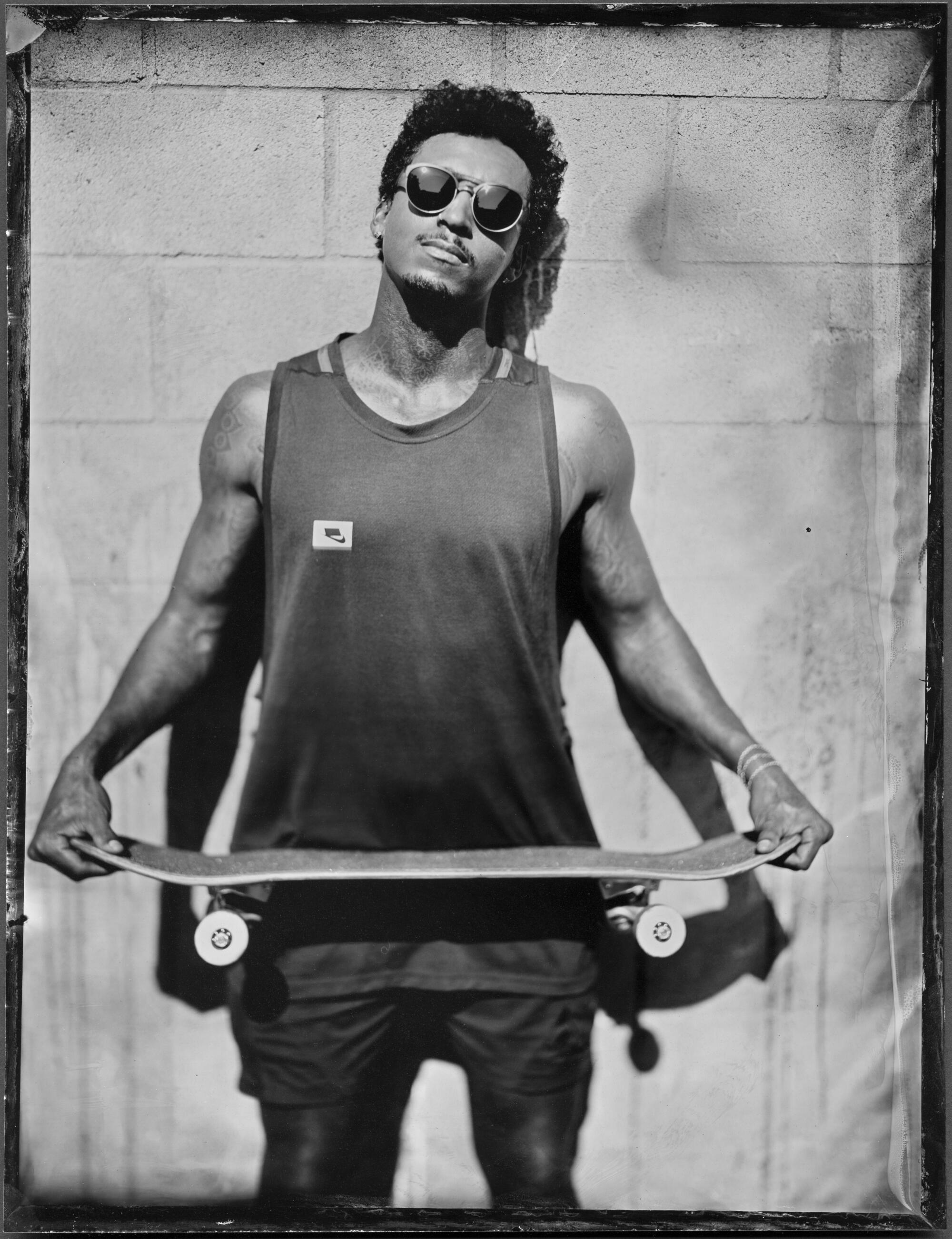

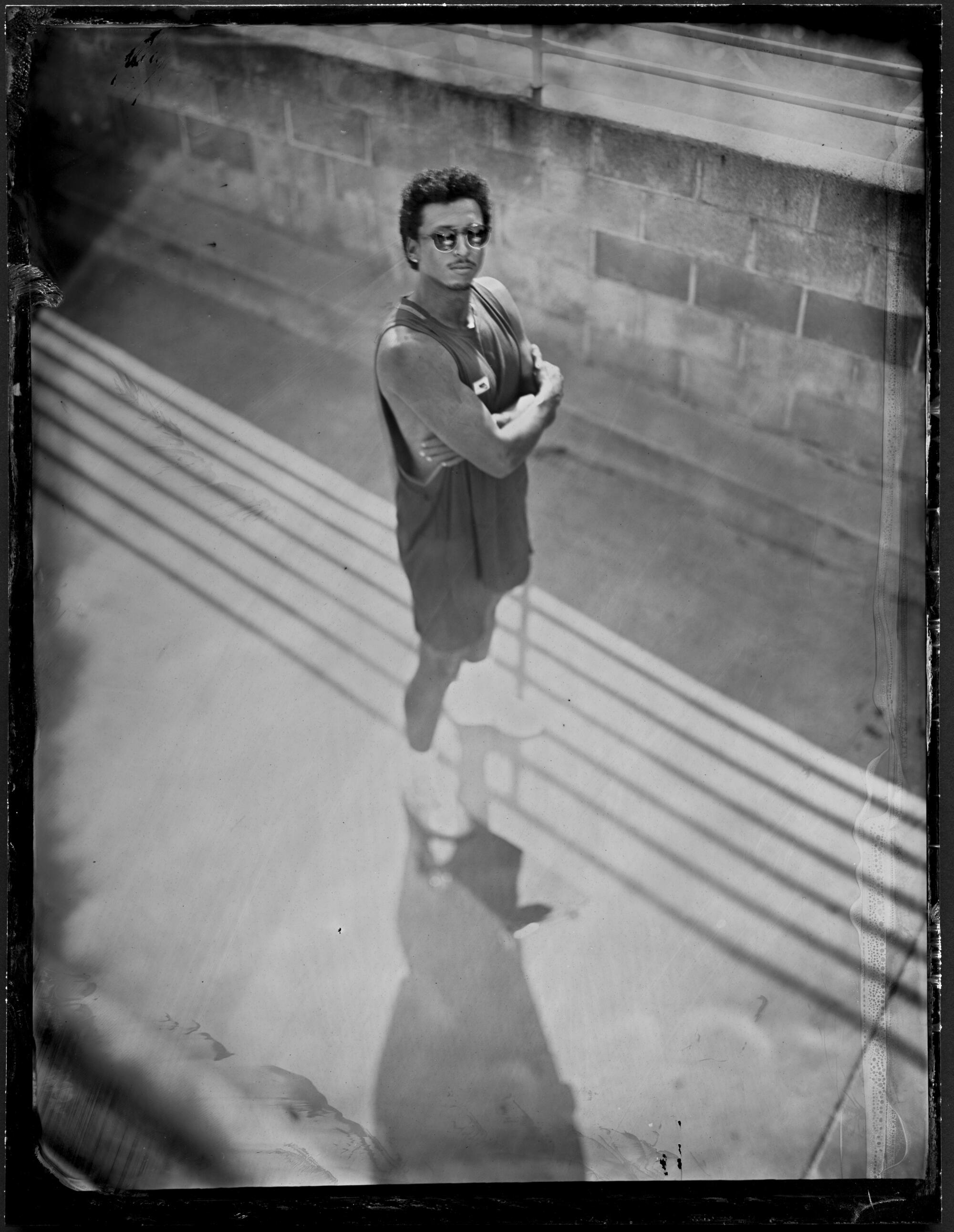

His trim build and thin goatee are not so imposing. Maybe the tattoos covering his entire body, creeping up his neck almost to his face, make him seem tougher.

“Cops will sit us down on the curb,” he says. “I’ve never actually been arrested but they’ve put me in handcuffs multiple times.”

They may not know Huston is regarded as the greatest contest street skater of all time. They may not know that prize money and endorsements have made the 26-year-old Laguna Beach resident a millionaire several times over.

And the trick that earned him yet another X Games title last fall, the Caballerial backside noseblunt to fakie? Doesn’t matter. When Huston hits the streets, which he still does on a regular basis, he becomes just another punk skating on public property where such activity is strictly prohibited.

“That part of skating is never going to change and I don’t want it to,” he says. “It’s the cool part. We’re skateboarders, we have rebellious ways.”

Next month, Huston will play this misfit role on an international stage as his sport debuts at the Summer Olympics. The four-time world champion arrives in Tokyo with a backstory that includes both prodigious success and struggle — a difficult childhood, nagging controversy and legal troubles that go beyond curbside detentions. Though he is already famous with skaters and 4.6 million Instagram followers, the Games could make him a crossover star in much the same way that Shaun White became a household name after snowboarding’s debut at the Winter Olympics.

“People think of skateboarding as kids skating at the 7-Eleven down the street,” says Neftalie Williams, a USC postdoctoral scholar and Yale visiting fellow who studies the culture of the sport. “In simple terms, Nyjah is an amazing athlete pushing what we can do and what comes next.”

::

There wasn’t much conventional about the way Huston grew up. His Northern California family was Rastafarian, strictly vegan, not much television, tight-knit with all four boys and a sister home-schooled.

The father, Adeyemi, was a talented skater, so there were always skateboards around the house. Huston recalls scooting them across the floor as a toddler, soon learning to ride on his knees. In 2005, his parents bought a skate park near their hometown of Davis.

“As a family,” mother Kelle says, “we were there six days a week.”

A young Huston blossomed. He was competitive by nature, refusing to go to bed until he beat his siblings at nightly board games. During the day, he applied an innate meticulousness to practice; he was the type of kid who arranged T-shirts by color in the drawer.

“He would go out into our skate park and do the tricks he already knew and do them in the exact order,” Kelle says. “He would not let himself move on to anything new until he had landed this long line of tricks.”

Though the sport has white, suburban roots, that did not prevent a skateboard company from discovering Huston — the son of a Black father and white mother — and signing him to a contract at age 7. Frail-looking with enormous dreadlocks, he entered a prestigious amateur contest in 2005 and took first place.

“Nyjah’s just sort of a rare breed,” Rob Dyrdek, a former pro skater and host of MTV’s long-running “Ridiculousness,” told the Times in 2010. “Someone that is so gifted and so focused at such a young age.”

For all his talent and devotion, Huston still felt “constant pressure from my dad. He was always pushing me to do really big rails. It was scary.” People in and around the family recall that life with Adeyemi — who could not be reached for this story — grew increasingly difficult as his son became a star.

“In simple terms, Nyjah is an amazing athlete pushing what we can do and what comes next.”

— Neftalie Williams, a USC postdoctoral scholar and Yale visiting fellow who studies the culture of the sport.

Adeyemi wanted to “control a lot of situations,” an industry executive says, starting his own skateboard company with his son as front man. He moved the family into further seclusion in Puerto Rico, making it harder for Huston to attend contests and fulfill sponsorship obligations.

The boy turned professional at 11, but he struggled to replicate his amateur success.

“I was really shy because I didn’t have much of a social life,” Huston says. “The other skaters could tell. They could see I wasn’t having any fun.”

When Adeyemi and Kelle separated in 2008, Huston’s siblings returned to the mainland U.S. with their mother while he remained with his father. Two years later, after Kelle filed for divorce and was granted full custody, Huston reunited with her, embarking on a very different sort of teenage life.

“Aside from skating, it was me being a normal kid,” he says. “I had friends. We were just skating and kicking it.”

::

Contest skating comes in several varieties. Vert style features aerial tricks off tall ramps. Park style is all about concrete quarter pipes and halfpipes common to community parks.

Street style is the most urban, with skaters sliding — or “grinding” — along handrails and the edges of planter boxes, executing maneuvers off stairs. “It’s closer to the ground,” Williams says. “Can you do all those tricks at speed, looking comfortable?”

Agility and flair have always been Huston’s strength and, if his life were a movie script, he might have started winning contests in those jubilant early days with his mother. But that’s not how it worked. Still young, he suspected that judges held his age against him because every stop on the professional circuit seemed to end with a second-place finish.

“I would give my all and not get what I thought I deserved,” he says. “It really hurt.”

His previous earnings were spent and he owed back taxes, putting his family in a financial pinch. “I didn’t even know what taxes were,” he says. “I was like, what? I have to give my money to who?”

Then, in 2010, Dyrdek started a tour called Street League Skateboarding. A 15-year-old Huston won the inaugural event in Arizona and finished the season as league champion, bringing home as much as $150,000 per contest.

“That was the moment when we needed something to happen,” he says. “It was a lot of relief.”

The following year brought an X Games victory, the beginning of a streak that has now reached 19 medals — most of them gold — over a dozen years, making him the most successful skater in the history of the premier competition.

“Not only was he consistent,” Dyrdek says, “he always did the hardest tricks.”

Executing a perfect 5-0 grind with his rear axle sliding along a rail, the board’s nose pointing skyward. Launching himself into the air, reaching down for a tail grab. Kickflipping in mid-glide with the board seeming to levitate beneath him, rotating on its long axis.

His artistry soon attracted endorsement contracts with the likes of Nike, Monster Energy drinks and Privé Revaux eyewear. At that point, he says, “it all started happening so fast.”

::

Like surfing, snowboarding and other so-called “action” sports, skating has always walked a cultural tightrope.

Its origins are based on lifestyle, getting together with friends, wearing certain kinds of clothes, speaking the language. In a video posted online, Huston and squad arrive at what looks to be a public school, grabbing a gasoline-powered hedge trimmer from the car to cut back hedges and expose a long railing along an outdoor ramp. They do tricks until the police arrive.

“Just got f—ing clipped out here,” Huston tells the camera.

Big-money contests with their rules and judges can seem jarring if not antithetical to this renegade vibe, so any pro star is bound to face pushback from a segment of the community. Some view Huston as too serious, too mercenary. At a 2012 contest in New Jersey, fans booed him.

“People assume they know you but they don’t,” he says. “I’ve made money from a young age but it’s never taken away from my love of skateboarding. I don’t just do this for money.”

Success and wealth have brought other problems. As an unusually prosperous 18-year-old on his own, he bought a $2.55-million San Juan Capistrano house in 2013 and became known for throwing wild parties.

Within a year, Orange County deputies had responded to multiple noise complaints, finding 200 — or was it 300? — people at the property on one occasion. Huston was later charged with assault stemming from a 2017 fight and ultimately pleaded no contest to misdemeanor disturbing the peace. His neighbors had grown exasperated.

“If it was me, I would have been mad too,” Kelle says. “I’m sure they were really glad when he moved.”

His new $3.6-million home in Laguna Beach has not seemed to draw as many complaints. Kelle calls it his “grown-up house” but he hasn’t steered entirely clear of trouble.

Last winter, Los Angeles prosecutors charged him with a misdemeanor for organizing a birthday party at a Fairfax district home that they characterized as a potential coronavirus superspreader. Huston says: “I genuinely feel bad about the situation.”

Sitting with a reporter, he is friendly and patient while facing questions. The dreadlocks of his youth have given way to a shorter cut, trimmed close on the sides, adorned by earrings. His responses are both articulate and tinted with skating patois, “sick” and “hype” tossed into the mix.

The COVID party, he says, was supposed to be a small, outdoor affair with caterers preparing teppanyaki for 30 or so socially distanced guests. But more people showed up, friends of friends arriving uninvited.

“I was actually trying to follow the rules,” Huston says. “I don’t want people to think I was being careless about people’s health and not taking the COVID situation seriously.”

If nothing else, the incident reinforced a point his mother has been making since he was young. You’re famous. People watch you. Anything you do wrong will be in the news.

“I don’t like to think of myself as famous because us skaters, we think of ourselves as normal people,” Huston says. “But I really do have to be more careful about what I do and the way I set examples for everybody.”

::

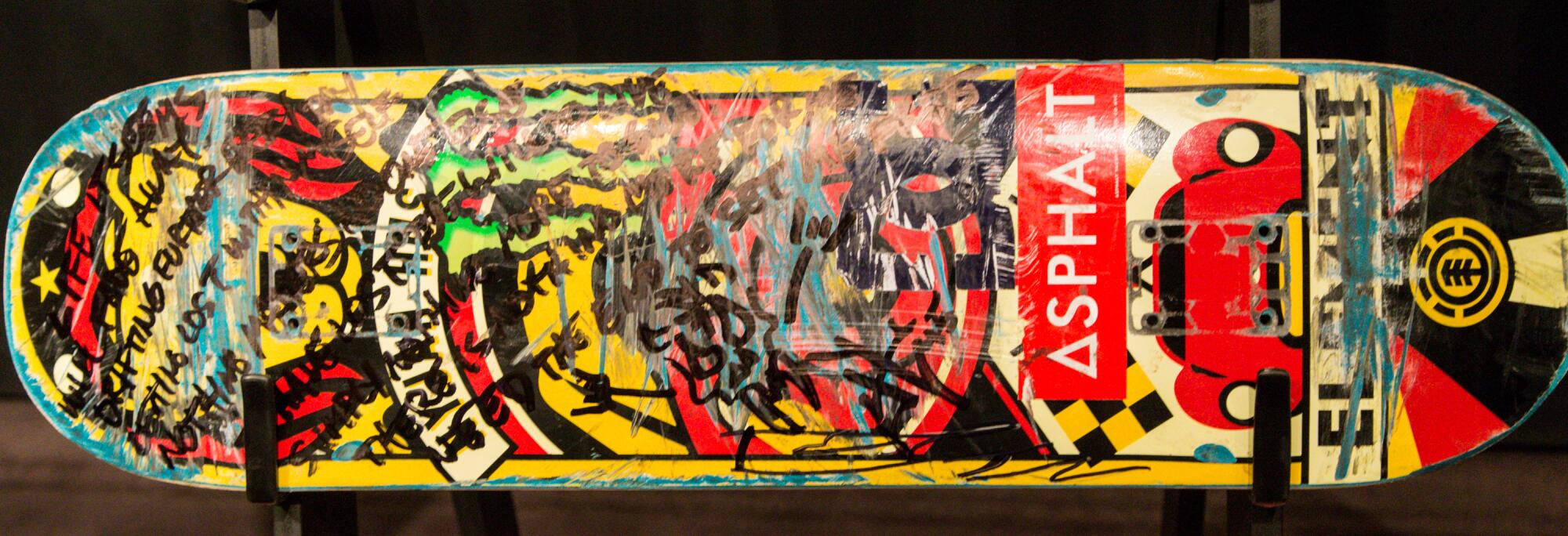

The San Clemente business park looks ordinary in almost every sense, with rows of plain, blockish buildings. Tucked among them is an unmarked warehouse that Huston has transformed into a personal, indoor skate park.

The cavernous interior is filled with smooth concrete floors and ramps and metal rails. The walls are painted black, ornamented with the brightly colored logos of his sponsors.

As the skater arrives on a sunny, breezy afternoon, his schedule includes a photo shoot and interview, some business matters and all those social media followers to be kept happy. As Williams of USC says: “People expect that when Nyjah drops a video, it will be mind-blowing.”

Someone brings him takeout so he can eat on the go. A friend is giving lessons to young skaters and an employee needs to ask about an order for custom hats. Red or black? Embroidered? Big or small logo?

“Let’s mock it up,” Huston says. “See how it looks.”

At some point, he needs to skate. Organizers of the Tokyo Olympics recently issued a blueprint of their street-style venue and Huston has studied it closely, looking for possibilities, explaining: “I feel like a kid when that stuff comes out. It’s a new toy.”

The course is reminiscent of Street League Skateboarding and has decent-sized rails, the longer the better for a skater whose youth has prepared him to go big, so Huston is working on a couple of new tricks he hopes to perfect by late July. He is trying to maintain a steady approach — never get too amped or too relaxed before a competition — but this one feels different.

There is an undeniable, creeping pressure.

“I don’t like thinking that way,” he says. “But that’s the reality — it’s the Olympics.”

A gold medal in Tokyo could be the crowning achievement in a life filled with highs and lows. It could vault his reputation above that of skating’s mainstream star and elder statesman, Tony Hawk.

That could translate into a higher Q score, more sponsors, more money. And maybe the next time he goes skating with friends at the park or outside some county building, the cops will recognize him.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.