Commentary: Stanford saga shows Pac-12 may no longer champion Olympic sports

Painful memories will endure from Misty Hartung’s year fighting for Stanford athletes in their battle with university leaders who chose to turn their backs on them.

First, there was Hartung’s son, men’s volleyball player Kyler Presho, telling her the news in July 2020 the school was cutting his program along with 10 other varsity sports virtually out of nowhere.

“The look in my son’s eyes the day he got cut is just something I will never forget,” Hartung says.

As American colleges begin to cut some sports, the effects could be seen on future Olympic medal stands.

Stanford gave the affected coaches and players zero notice. Other schools had announced cuts in the months prior, using the pandemic as cover for budgetary slashes that may have felt inevitable for some time. But this was Stanford, long the emblem of what the “student-athlete” experience should be, and now the West Coast’s Ivy League peer with a $28 billion endowment was saying there wasn’t enough money to save sports that routinely bred U.S. Olympians?

Hartung, who lives in San Clemente and works in sales, soon found herself playing the role of fraud investigator, joining parents from each of the discarded programs on the front lines. While putting together the vision and funding for a lawsuit against the school, she heard stories of Stanford’s administrative indifference straight from the confused athletes and absorbed their heartbreak over a Zoom screen.

“We know where our bread is buttered. We’re focused on the revenue sports and winning in football and men’s basketball.”

— New Pac-12 commissioner George Kliavkoff

“They looked defeated and helpless,” Hartung says. “They weren’t sure what to do. They would send messages saying, ‘We’re still competing for a school that doesn’t want us.’ ”

On May 18, the same athletes shared their elation with Hartung when Stanford announced it was reversing course and reinstating all 11 programs, keeping the Cardinal “36 Strong,” the alumni’s proud label for all the school’s sports programs.

Whatever the reason for the about-face — Stanford certainly was not going to cite the oncoming lawsuit from attorney Jeffrey Kessler, one of the titans of sports and antitrust law, in its explanation — Hartung was simply relieved the efforts from all corners of the affronted Stanford community had somehow prevailed in the end.

The Pac-12 hires George Kliavkoff, an MGM Resorts International executive, as its commissioner. He has no college sports experience.

Still, she can’t unsee the last 10 months.

“I learned a lot about the underbelly of college sports,” Hartung says. “When you talk about college sports, we think about the athletes a lot, and the teams, but from the university perspective, they don’t see it that way. These aren’t kids with dreams fulfilling their college athletic experience. These kids are just numbers on a spreadsheet, and they’re running a business. That athletic department model is broken.”

Within the unrelenting college sports news cycle that defined the 2020-21 pandemic school year — from return-to-play machinations to big-name coaches contracting COVID-19 to name, image and likeness debates to athletes beginning to organize for their rights — it would be easy to forget the Stanford saga. Especially now that justice has been restored at the 11th hour. But if we care about the future of college sports, we should not forget what this episode taught us about higher education’s priorities and the standing of the “student-athlete.”

All year, I’ve been asking why.

I could not accept that Stanford did not have the money to run these programs, particularly after hearing that the cut sports had no problem raising millions of dollars straight from the pockets of their successful and passionate alumni bases in the weeks after the announcement. Yet Stanford athletic director Bernard Muir would not meet with the teams or theorize possible solutions for sustainability?

The Pac-12’s dominance in the NCAA men’s basketball tournament is helping the conference restore its credibility with a national audience.

I came across an interview that then-Dartmouth athletic director Harry Sheehy did with the student newspaper, The Dartmouth, last summer about the Ivy League school’s decision to cut five sports. Sheehy said he had been told by Dartmouth president Phil Hanlon before the pandemic that he was considering reducing the number of athletes on campus by 10 percent “due to admissions priorities.”

“Because of what President Hanlon desired to have us give back to the admissions process, even without the budget problem, we might very well be sitting here today having done the same thing,” Sheehy admitted. “The budget problem simply exacerbated that it needed to be done.”

Stanford has made no such admission, but if it had, it would have actually made more sense than blaming it on the costs of running a squash program.

Stanford was ready to hand 240 coveted undergraduate admissions slots back to the university’s general pool, choosing future Nobel prize winners or the children of foreign billionaires over highly motivated athletes, some of whom would not have had the grades or test scores to be admitted without their athletic prowess.

It’s not surprising that Stanford’s president would think along the same lines as Dartmouth’s. Many of America’s top universities were mortified by the Varsity Blues scandal, which used athletic admissions slots to create a “side door” for undeserving non-athletes to get into elite schools. Stanford’s sailing program, which was one of the sports cut, was implicated in the scandal.

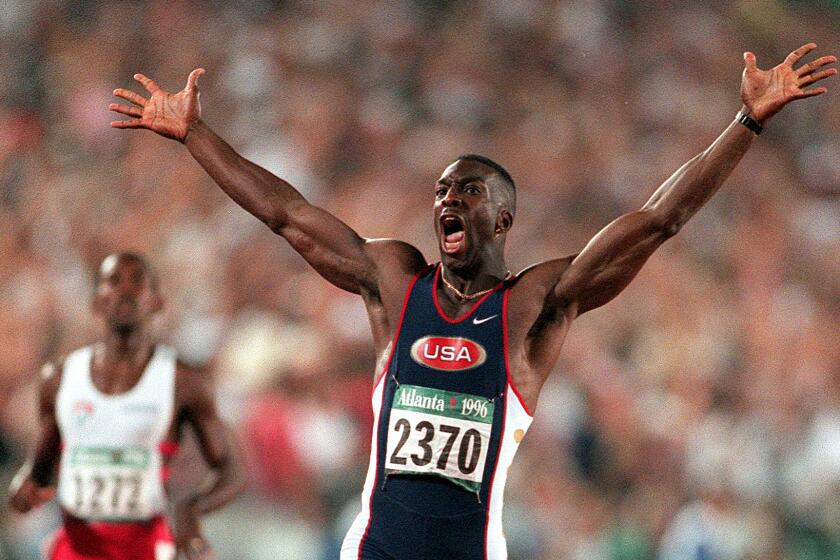

Dartmouth saying it wanted fewer athletes on campus was one thing. Stanford, a Pac-12 school that has harbored the ideals of the Olympic movement, was quite another.

“It’s super disappointing to me because I think of Stanford people as so well-rounded,” said Matt Fuerbringer, a Stanford men’s volleyball alumni who went on to a pro career.

Rick Singer’s pitch: For a fee he could help get children of affluent parents onto USC, UCLA teams, even if they didn’t play the sport. Most didn’t.

“One of the first parties I went to, another freshman had climbed Mount Everest. One was the son of a diplomat who had barely lived in the U.S.A. Then you meet a guy that was up at 4 a.m. to do a sport there’s no glory in while excelling in the classroom. I’m sure they’ll find 240 people, but I don’t know if you get as well-rounded of students.”

Hartung says that some of the early pieces of evidence that the plaintiffs requested in their lawsuit against Stanford were documents relating to the school’s admissions priorities.

“I don’t think any university wants its admissions goals known,” Hartung says. “That would be embarrassing for any university, especially with the PR nightmare [Stanford] has gone through. That was definitely not something they were willing to open up.”

Stanford backed down because big donors threatened to pull support — and because tens of millions had been committed to keeping these 11 sports. It became easier to see a path forward for non-revenue sports to be self-endowed and no longer a drain on the more important pursuit of success in football and men’s basketball.

Monetizing those two sports is now all that matters to university higher-ups — another reality that was reinforced by Stanford’s actions.

The “We Are United” movement showed unpaid college athletes without a union could speak up for themselves and be heard while asked to play during a pandemic.

George Kliavkoff, the Pac-12’s new commissioner, affirmed as much in his introductory news conference.

“We know where our bread is buttered,” Kliavkoff says. “We’re focused on the revenue sports and winning in football and men’s basketball.”

Depending on who you are, that notion could be seen as either inspiring or foreboding. If you’re a coach or athlete in a non-revenue sport in the “Conference of Champions,” it is, at a minimum, fully revealing.

The members of 34 Stanford sports already learned it.

Wrestler Shane Griffith won a national championship this year while wearing a singlet with no Stanford logo, an unmistakable statement of what’s been lost. The women’s synchronized swimming team won the national title under the assumption it was the team’s last season. Men’s volleyball players I spoke with did not wear their Stanford gear this year unless they had to.

Misty Hartung’s son, Presho, has the option of an extra year like all NCAA athletes who competed during the pandemic. Even though he can now use that year in Palo Alto thanks to Stanford’s reversal, he has decided to spend it playing for Hawaii.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.