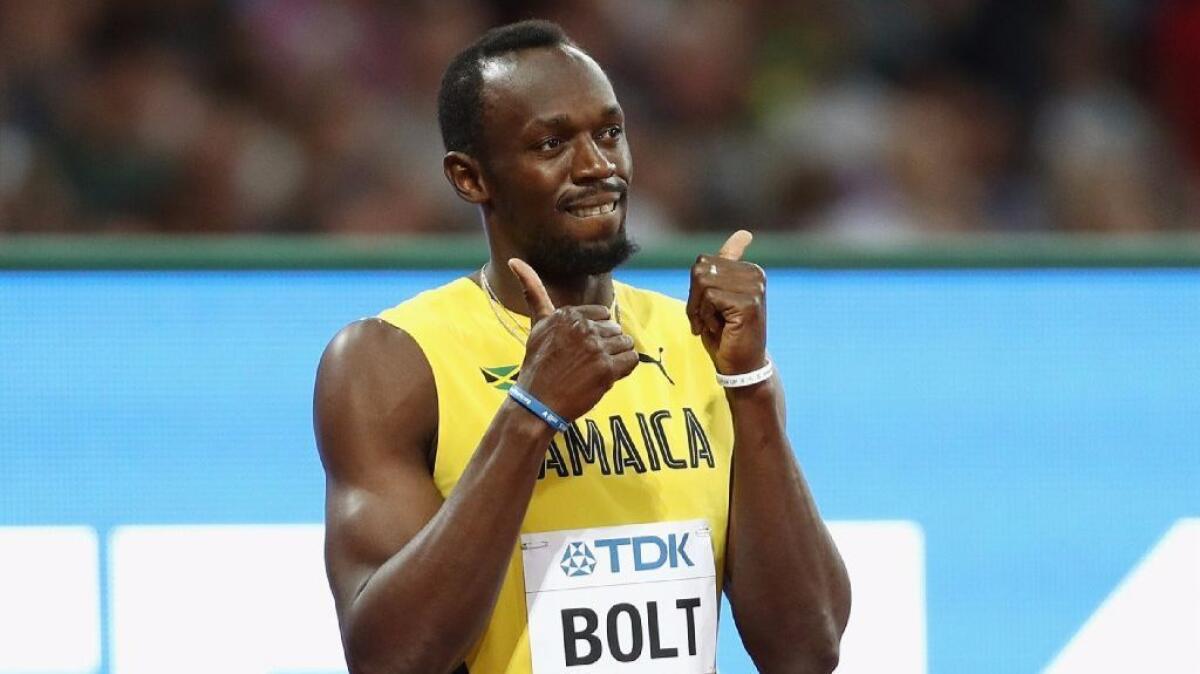

Usain Bolt has a clear image of how his final race will play out

Think of the man as pure physics, that tall body like a math equation, cadence multiplied by stride length.

Or consider that something less measurable has propelled Usain Bolt to greatness, something along the lines of talent blended with grit.

“Unbeatable,” he told reporters this week. “Unstoppable.”

The fastest man in history will burst from the starting blocks on Saturday for what he says will be the final 100-meter dash of his career. Competing at the 2017 world championships in London, the 30-year-old is hoping to add more gold to a list of unprecedented feats.

Start with his record at the Olympics, where he has dominated the sprints for nearly a decade, ranking as the only athlete to win the 100 and 200 three consecutive times.

His world championship resume includes 11 victories against a single loss, when he false-started the 100 in 2011.

Along the way, Bolt has secured world records in both of his specialty events and has earned additional wins as the leader of Jamaica’s 400 relay team.

“I think no athlete wishes their record will ever be broken in their lifetime,” he said. “I want to brag to my kids when they’re 15 or 20 and say ‘Look it, see, I’m still the best.’”

It is a mark of this resolve that Bolt insists upon calling himself an underdog this weekend.

True, he has run the 100 only three times in 2017, with a pedestrian 9.95 as his best finish. But, coming off the Rio de Janeiro Olympics last summer, this has been a slow year.

Christian Coleman of the U.S. is the only sprinter to break 9.90. Another top rival, Andre De Grasse of Canada and USC, has withdrawn from the championships with a strained hamstring.

And one more thing in Bolt’s favor: He usually saves his best for big races.

“He is a championships man,” Christophe Lemaitre of France said after finishing third to him in the Olympic 200 last summer. “A really unbelievable guy.”

Growing up in northwest Jamaica, Bolt always stood taller than the other boys. Childhood scoliosis did not prevent him from showing promise as a young hurdler and high jumper, not to mention a cricket player. By age 14, he had switched to the sprints, drawing attention in national meets.

The 2002 junior world championships served as a global debut for a prodigy who soon became his sport’s preeminent figure.

“I just blew my mind. And blew the world’s mind.”

— Usain Bolt

Asked to name a favorite memory, Bolt often mentions his 200 victory at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. In addition to securing his first sprint double, he broke a world record that Michael Johnson had held for more than a decade.

“I just blew my mind,” he said at the time. “And blew the world’s mind.”

A year later at the world championships, Bolt took the 100 in 9.58 seconds, a record that remains a tenth of a second faster than the closest rival.

There were other notable accomplishments, capped by three golds in Rio, but athletics are only part of what has set him apart.

Boyish and eager in the spotlight, he likes to prod the crowd into cheering, then press a finger against his lips for quiet. Each win inspires another dance around the track, another chance to strike that signature pose with head tilted back, left arm outstretched.

These antics often give way to outlandish news conferences from an athlete fond of saying: “I am a living legend.”

Former sprinter and current television commentator Ato Boldon once told The Times: “His performances get your attention. His personality is what has kept the attention of the entire planet.”

There might be no explaining Bolt’s persona. As for his athleticism, researchers have their theories.

Not many sprinters stand 6-foot-5, a height that makes it tough for Bolt to get his legs churning toward the finish line.

His cadence — the rhythm of his strides — tends to be slower than that of his opponents, especially out of the blocks. But the difference is not as great as expected, and his length more than compensates.

Stephen Piazza, a kinesiology professor at Penn State, cites the 100 Olympic final in Beijing as an example.

Analysis shows that Bolt’s cadence was 4.69% slower than the rhythm set by another sprinter in the race, Walter Dix of the U.S. Bolt’s step length, however, was 7.49% greater, allowing him to cover the distance in 41 steps, three fewer than Dix.

Saving precious time, Bolt won in 9.69 seconds. Dix finished third in 9.91.

“It is very difficult to pin down why Bolt can turn his legs over as fast as he can for a man that tall,” Piazza said. “It could be something to do with muscle composition. It could be the proportion of his limbs or his training methods or psychological factors.”

All of that might also explain his knack for bouncing back from repeated injuries and the clutch performances that have made him a bright spot in a troubled era for track and field.

Many of the sport’s top names have been caught using performance-enhancing drugs in recent years. The entire Russian track team has been banned from international competition.

Bolt has never tested positive but has felt the sting of cheating.

When officials retested samples from the 2008 Summer Games, they found that teammate Nesta Carter had used a banned substance. Bolt and the rest of the Jamaican squad were retroactively stripped of their gold in the 400 relay.

This week, Bolt put an optimistic spin on the situation, reaffirming his belief in the sport.

“I said a couple of years ago that it had to get really bad,” he said. “So, for me, the only way track and field has to go is up.”

As for his own legacy, great athletes are known to renege on retirement plans, but Bolt is expected to stick with his decision.

That makes the world championships — where he’ll compete in the 100 and the relay — one last chance to shine. Bolt won his 100 heat on Friday in what he called a “very bad” time of 10.07.

Saturday brings an opportunity to rebound in the semifinals and final.

There is little doubt about how Bolt sees this story playing out. Or how he would like to be viewed by generations to come.

“Unbeatable,” he repeated earlier in the week. “For me, that would be the headline.”

Follow @LAtimesWharton on Twitter

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.