Mental illness or brain injury? Driven by voices to commit crime, Titus Young is in prison but still believes he could play in the NFL

Titus Young spent two seasons with the Lions before the team released the troubled receiver.

The former NFL wide receiver with “FEAR GOD” etched on his biceps and his mother’s name written over his heart opened the worn black composition book with a faded newspaper photograph of retired NBA player Metta World Peace taped to the cover.

Titus Young was once classified among the most dangerous inmates at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility in downtown Los Angeles and spent most of his days in lockdown. In early 2017, he started to write.

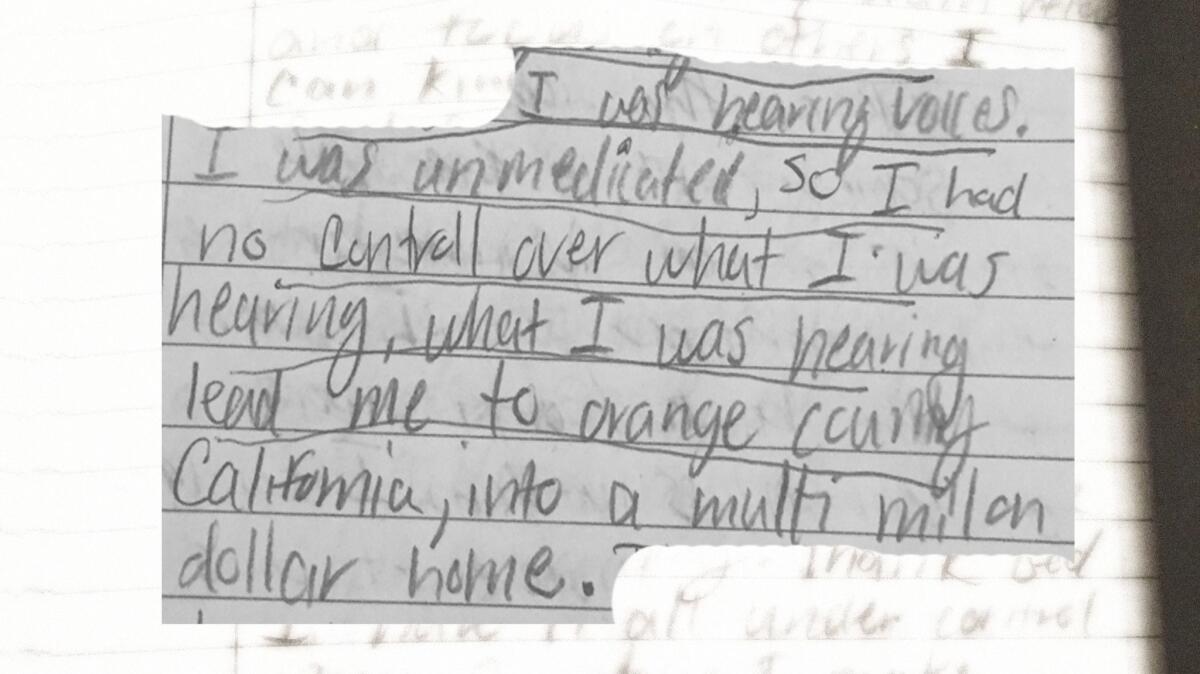

“I have made so many mistakes I have become a little ashamed of being Titus Young,” he scribbled in fast-paced printing. “A lot of the stuff I have done was out of my control during the time. ... I was hearing voices.

“Hearing voices is no joke, it’s actually very scary. I feel like someone is trying to come kill me.”

The diary is 141 pages, started Feb. 2 and finished about two months later. Young, who hopes to turn it into a book, asked a relative to share excerpts with the Los Angeles Times rather than agree to an interview.

Entries meander from one topic to another, some written in textbook cursive, others in printing that’s barely decipherable. Young, then 27, wrote about wanting to be a better father to his young son. About gnawing hunger, cold and feeling homeless during four months in lockdown. About mental illness.

And about football. Always football.

“God is great still being behind bars because this has given me a chance to share my side of my story, which coming from the public has been so negative,” Young wrote.

His once-promising career with the Detroit Lions disintegrated in a series of altercations and worrisome behavior. He accumulated at least 25 criminal charges — including 10 for assault or battery — in Southern California since 2013. He bounced between mental health treatment facilities, courtrooms and jail.

“I want to be free,” Young wrote. “I believe God has a plan for me and deep down I believe it’s to dominate the NFL.”

The collision lingers in E.C. Robinson’s mind.

The former football coach at University High School in West L.A. witnessed plenty of big hits. But during a 2006 game against San Pedro, Robinson watched Young slam into an opposing tight end. The player went one direction, the ball went another. Young threw himself at opponents this way, lowering his head before impact and turning his body into a missile.

“That was the worst I’ve seen,” Robinson said. “It’s one hit where I thought maybe something happened.”

Perhaps that’s when the trouble started.

Young didn’t look like a football player when he arrived at University, maybe 100 pounds and not taller than 5 feet. Robinson laughed when Young predicted he would play. The impulsive, charismatic son of two pastors didn’t lack confidence.

“I was a very immature kid,” Young told a teammate in a video interview during his senior year. “No one could tell me anything. I always thought I was right. Finally, I found out I was the person who was being bad, the person that no one could talk to. I was tired of being the bad person in the dean’s office. I always wished I was someone else.”

In another video, of his football highlights, Young shouted: “Who can stop me? Who can stop me?” An off-camera voice replied: “No one.”

Young’s world-class speed and glue-like hands earned a scholarship to Boise State. The combination made him one of the country’s most feared wide receivers. The fear also took on other forms. Coach Chris Petersen suspended Young three times, including much of his sophomore season after a scuffle with a teammate.

More than a dozen of Young’s Boise State teammates and coaches, including Petersen, either declined to comment or didn’t respond to interview requests.

Young was chosen by the Detroit Lions in the second round of the 2011 NFL draft. After what appeared to be an uneventful rookie season, he unraveled. He sucker-punched teammate Louis Delmas during an offseason workout. He head-butted an opponent. He intentionally lined up in the wrong place on the field during a game. He threw a tantrum at a Detroit-area cellphone store. He posted a series of bizarre messages on social media. He snapped at strangers without provocation. He couldn’t sleep. He grew paranoid.

“He was ill-prepared,” said Marjani Maldonado, Young’s former girlfriend and the mother of his son. “When he got to Detroit, he wasn’t the biggest player on the team anymore. That messed with his mental side. He was used to having the spotlight, the attention on him.

“Titus doesn’t take direction very well. If somebody tried to coach him or teach him how to do it a little bit better, Titus would say, ‘No, I’ve got it.’”

Young’s parents, Richard and Teresa, didn’t respond to interview requests for this article, but in court documents and previous interviews, the family linked the alarming behavior to a concussion during Young’s rookie season. He told a cousin and close friend, Ezekiel Phillips, about absorbing a hard hit, feeling dazed, shaking it off and continuing to play. The Lions’ injury report never mentioned it.

Maldonado said Young didn’t want to believe he suffered from a mental health problem. Blaming concussions seemed easier.

While packing for a trip to Las Vegas in 2012, Maldonado heard Young telling someone to stop recording. He was speaking to a smoke detector. The device beeped every few seconds because of a low battery. Young thought the detector contained a camera. Maldonado realized something was wrong, something deeper than the passing effects of a concussion.

The day after the Lions released Young in February 2013, the Rams claimed him. He lasted 10 days.

Young ended up outside Robinson’s home, rambling that he would be the Rams’ top receiver in the coming season. He appeared to be in a daze. Robinson reminded Young the Rams had cut him. Young didn’t understand.

Titus Young's brief NFL career with the Detroit Lions

| Year | Targets | Catches | Yards | Touchdowns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year2011 | Targets 86 | Catches 48 | Yards 607 | Touchdowns 6 |

| Year2012 | Targets 56 | Catches 33 | Yards 383 | Touchdowns 4 |

Source: Pro-football-reference.com

When Phillips stopped at a gas station not long afterward, Young tried to exit the car to escape invisible pursuers.

“They’re going to get us,” he told his cousin.

Phillips locked the doors and drove to the Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at UCLA.

Mike Ornstein, who negotiated a handful of marketing deals for Young, visited him at the hospital. He had pleaded with the family to seek treatment.

“They’re churchgoing, God-fearing people that believe Jesus Christ will save everything for their kid, and that’s good when everything is good,” Ornstein said. “When you have a crisis like this, it’s not the best group to be around. … This guy needed professional help and they were trying to keep him at home.”

Young wore sunglasses and seemed doped up from medication. The happy-go-lucky kid Ornstein knew had vanished. Doctors at the hospital diagnosed Young as bipolar.

“Having bipolar has pretty much torn down my life,” Young wrote in the diary. “It’s been four years of fighting so many different behaviors. When I was first diagnosed, I didn’t want to believe it because I felt my life was too perfect to have bipolar. Football players don’t take medicine. I’m macho. Put me back on the field. But, no, that’s really not what I needed.”

About 9 p.m. on May 4, 2013, Young walked out of a Chevron in Laguna Hills without paying for a candy bar, bottle of water and box of Black & Mild Cigars. Young was carrying his infant son, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department report noted, and pretended to shoot cars with a finger as he drove away.

Two hours later, the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department received a call about Young sitting in his black Ford Mustang convertible outside the Moreno Valley home of Maldonado’s parents.

“Subj has a history of mental health issues/unk what kind,” the dispatch log said. “Appeared catatonic.”

Later that night, deputies arrested Young on suspicion of impaired driving. They impounded the Mustang. After being released on bail, Young was arrested again 15 hours later when he scaled the barbed-wire-topped wall of the impound lot to retrieve the car.

Richard Young blamed football-related concussions for his son’s “severe mental problems,” an Orange County sheriff’s deputy wrote in a report on the gas station incident.

“Richard told me Young often acts catatonic,” the report said, “and would not be able to speak coherently to me.”

Maldonado, who had already broken up with Young, asked for a restraining order. She said recently that her parents pushed for the restraining order and Young never harmed her.

“[Young] has been clinically diagnosed with a mental disorder and I am afraid of what he is capable of doing,” Maldonado wrote in the application. “He will say things like, ‘I understand why O.J. killed his wife.’ ... He has got mad and yelled at my neighbors and tried to fight multiple people that he doesn’t even know.”

She worried about the text message he sent her describing himself as “the king.” She didn’t think he wanted to get help.

The voices returned a week later.

“What I was hearing led me to Orange County, into a multimillion-dollar home,” Young wrote in the diary. “Something was telling me to go get on the freeway and drive.”

Around midnight, he entered a condominium in San Clemente through an unlocked sliding glass door on the second floor. Bill Plattos, an Army veteran and real estate broker, heard footsteps on the hardwood floors.

He grabbed a Model 94 Winchester from under his bed. When Young burst into the bedroom, Plattos almost pulled the trigger. Instead, he yelled. Young scampered away.

Orange County sheriff’s deputies chased Young through the neighborhood and tackled him on the front porch of another home. During the scuffle, Young grabbed one deputy’s throat and clawed another’s hand before they handcuffed him.

Young denied everything, even the arrest, to deputies. He told them he couldn’t hear because of “selective listening.” He claimed he didn’t remember anything because of too many concussions while playing in the NFL. He challenged a deputy to fight.

Young bounced in and out of treatment centers and eventually landed in Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital in early July 2014. He had been accused of assaulting four people in the previous two months. Brian Hurwitz, then Young’s attorney, visited the family in the hospital.

“I told my mother don’t bring my attorney,” Young wrote in the diary. “To my surprise, there he is.”

When Hurwitz told Young he couldn’t go home, the former football player punched the attorney, according to a L.A. County Sheriff’s Department report. Young knocked Hurwitz unconscious and broke his nose.

Months later, L.A. County Superior Court Judge Michael J. Schultz sentenced Young for the attack on Hurwitz: five years of probation, 191 days already served in jail and a year of inpatient treatment at the Crosby Center, a facility in Escondido.

Young had already spent three months at Crosby. A psychologist at the center, Robert Knol, testified that previous clinics misdiagnosed Young as bipolar or schizophrenic. He actually suffered from symptoms of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, Knol said, the neurodegenerative disease better known as CTE that’s related to traumatic brain injury.

Knol told the judge medication wasn’t effective for Young, so they weren’t using any.

Larry Burns, the center’s director, repeatedly told the court Young was misdiagnosed.

“He’s a fine young man,” Burns testified. “He was overmedicated. He went sideways uncontrollably. When we got him, we basically decompressed him and he’s been a model. And I see this kid going places.”

During a brief statement to the judge, Young said, “I have brain trauma” and apologized for attacking Hurwitz.

“This is the biggest chance that you’re given. … You will not get another one from me,” Schultz told Young. “You have to figure out a way to control your temper and take ownership of it.”

The judge warned Young this was his last opportunity to avoid serving time in prison.

Perched on a hill, the 4,000-square-foot home where Young spent the remainder of 2015 looked like a mansion. But in his jailhouse diary, Young described the Crosby Center as “prison.”

Crosby Center staff shuttled patients between the home and a nearby office. Young participated in group therapy with former NFL players in addition to neuropsychiatric tests, biofeedback, brain scans and acupuncture.

“The guy is a teddy bear,” recalled Pete Daniels, one of the center’s employees.

The center’s website describes Crosby as “the premier destination for treating serious brain-related disorders ...” However, in March 2015, the NFL Players Assn. issued a “fraud alert,” describing director Burns as having “accumulated numerous convictions for felony FRAUD-related violations.” Burns called the alert “a slander.”

In a court filing to oversee the almost $600,000 left in Young’s bank account, his mother and sister said his conditions included acute psychosis and schizophrenia related to a traumatic brain injury.

Daniels said a key part of Young’s treatment was stabilizing him on the right medication, despite Knol’s testimony saying none were needed.

The probation report said the center discharged Young in January 2016 after he assaulted a staff member. Burns denied any assault occurred. No calls for service by the Escondido Police Department or San Diego County Sheriff’s Department match such an incident.

Young — no longer taking medication, Burns said — returned to South Los Angeles.

“My mind-set during the time wasn’t focused and disciplined to go back to the NFL,” Young wrote in the diary. “Obviously I had no business being back in the hood. I have to move far away from California.”

Two years have passed since a shirtless man gripping a dark object jogged down West 64th Street as midnight approached in L.A.’s hardscrabble Harvard Park neighborhood.

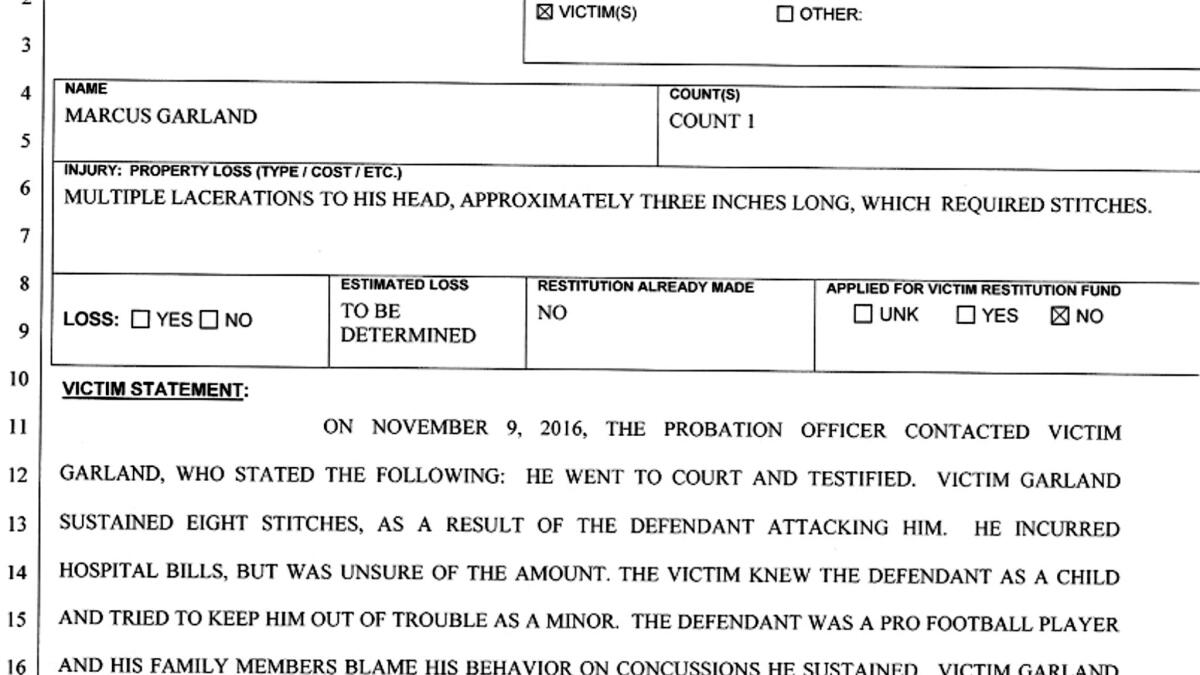

Sweat made Young’s chest glossy despite the January chill. When he encountered Marcus Garland near an intersection, he rained punches on his longtime neighbor’s head. No words, no warning.

They had never fought or argued, Garland later testified in L.A. County Superior Court — not even earlier in the day when Young took Garland’s bike without permission and announced that he had urinated on himself.

Garland said the blows felt as though they were coming from a piece of metal. The beating continued after he tumbled to the ground. He needed eight stitches to close the gash on the right side of his head.

L.A. police officers found Young hiding behind a large plant in his parents’ backyard a half-block away. Richard Young told officers his son tried to fight him, the probation report said. He tried to fight the officers, too, before they took him into custody.

Phillips bailed out Young at 12:25 a.m. and drove him to the Crosby Center.

Later that morning, Escondido police responded to the center for a welfare check on because Young was “acting aggressive, yelling and speaking to a relative in an aggressive manner,” according to police.

He wasn’t taken into custody and surfaced that evening in downtown Carlsbad. He harassed an employee for drugs at a clothing store, tried to start a fight, broke a video game machine at Pizza Port Brewing Co. and attempted to fight passers-by in the street. Police arrested Young and he was later charged with five crimes, including battery, making a criminal threat and vandalism.

“My fight or flight in my brain was off and that could be due to head trauma suffered while playing football,” Young wrote in the diary, a year after the arrest and a stay at Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk. “All I know now is I’m back to normal and I take good medication and I’m not ashamed of it either.

“It’s kind of hard for me to think wisely in sticky situations where I feel threatened. Taking the medicine allows my mood to be stabilized and helps with hearing voices. Yeah, I have heard voices, as well. The voices came and came from the bipolar. It’s usually when I let my brain relax and focus on others. I can kind of hear them.”

Along with being sentenced to four years at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco for the Garland assault, Young was given two years to serve concurrently for the Carlsbad incidents. Inmate No. BC9104 is eligible for a parole hearing in March.

“It is unfortunate if the defendant suffers from brain injury as a result of playing football,” the probation report said. Nevertheless, it noted, Garland could have been “severely injured or died, due to being struck numerous times in the head.”

Garland told the probation officer he wanted Young to “do time” and blamed the assault on drug use, not a brain injury.

When Ornstein talked to Young a couple of months ago, the conversation revolved around an NFL comeback. Ornstein told him to stay in shape, run sprints, stay out of trouble, the usual admonitions. What Ornstein didn’t have the heart to say is returning to the league is all but impossible.

Maldonado, the former girlfriend, thinks Young needs to get out of L.A., move somewhere secluded, understand he’s out of chances, surround himself with the right people.

Robinson, the high school coach, still wonders how someone with so much ability, such a magnetic personality could fall so far. He doesn’t know what Young can do for a living on the other side of a prison wall.

Plattos, who can’t shake the memory of Young bursting into his bedroom, doesn’t believe this will end well.

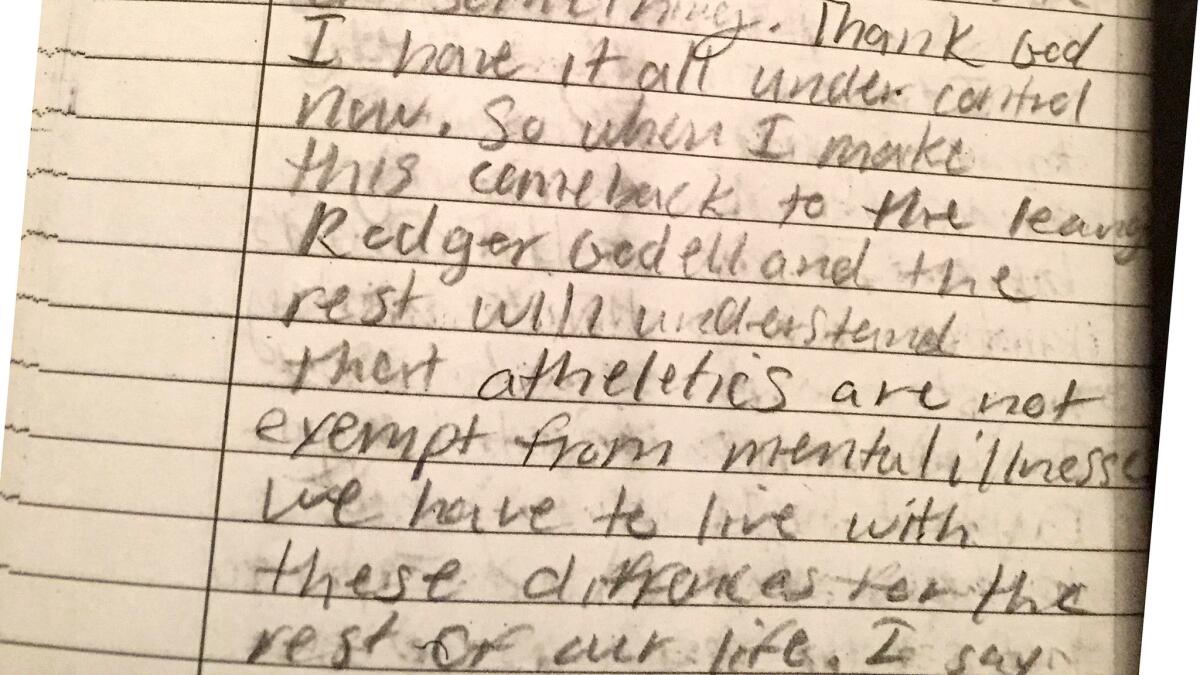

“Thank God I have it all under control now,” Young wrote in a diary entry titled “I’m flawed.” “So when I make this comeback to the league, Rodger Godell [sic] and the rest will understand that athletes are not exempt in mental illness. We have to live with these differences for the rest of our life.”

____________

FOR THE RECORD

3 p.m.: An earlier version of this story incorrectly quoted a journal entry as saying “So when I make this comeback to the league, God and the rest will understand that athletes are not exempt in mental illness.” Titus referred in the journal to Roger Goodell, the NFL commissioner, using a different spelling: “… Rodger Godell and the rest will understand that athletes are not exempt in mental illness.”

____________

Follow Nathan Fenno on Twitter @nathanfenno

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.