San Francisco 49ers legend Dwight Clark dies at 61

Dwight Clark, the receiver with movie-star looks and charisma whose iconic catch launched a San Francisco 49ers NFL dynasty, died Monday, less than two years after revealing he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 61.

The news was announced on Clark’s Twitter account by his wife, Kelly.

“I’m heartbroken to tell you that today I lost my best friend and husband,” she wrote. “He passed peacefully surrounded by many of the people he loved most. I am thankful for all of Dwight’s friends, teammates and 49ers fans who have sent their love during his battle with ALS.”

Clark died at his home in Whitefish, Mont., where he recently relocated from the Bay Area.

“For almost four decades, he served as a charismatic ambassador for our team and the Bay Area,” the 49ers said in a written statement. “Dwight’s personality and his sense of humor endeared him to everyone he came into contact with, even during his most trying times. The strength, perseverance and grace with which he battled ALS will long serve as an inspiration to so many.”

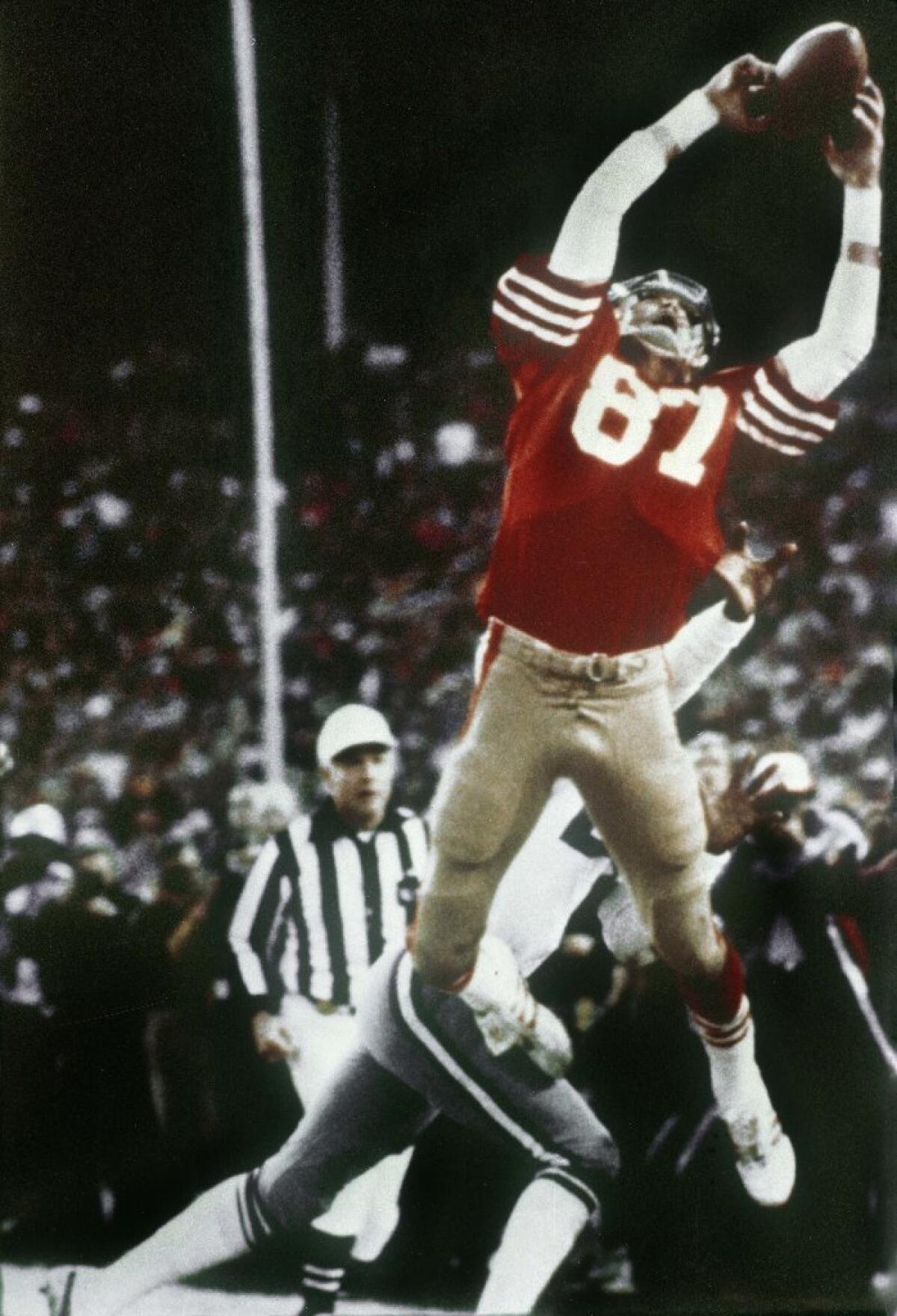

The 6-foot-4 Clark will be forever linked to Hall of Fame quarterback Joe Montana, who threw him the pass that would become known as “The Catch.” That was Clark’s six-yard grab in the back of the end zone with 51 seconds left against the Dallas Cowboys in the NFC Championship game on Jan. 10, 1982. The fingertip reception clinched a 28-27 win over the mighty Cowboys and paved the way for the first of five Super Bowl victories by the 49ers.

Clark, the dashing, 10th-round draft pick out of Clemson in 1979, was suddenly the toast of San Francisco. He was so popular that a developer paid him $15,000 a year — half of the receiver’s salary from the 49ers — to live in a luxurious condominium in the heart of the city.

“He had done this in L.A. with movie stars or whatever,” Clark recalled in January. “But he’s paying me 15 grand to live at 101 Lombard. I’m single, and the place had three levels. It was one-bedroom, the bed was at the bottom. The middle floor was the family room, kitchen and dining room. And the top was a roof that looked out over the Bay Bridge. It was unbelievable.”

Clark got a big pay raise after that season, just before NFL players went on strike in 1982. That led to a stretch Clark called “the most incredible 57 days of my life.”

“So, we play two games and then go on strike,” Clark said. “And I’ve got that place, money, notoriety and a Super Bowl ring. It was like being Huey Lewis.”

That was a far cry from Clark’s humble beginnings with the team, when Montana confused him for a kicker when they were introduced. It wasn’t long, though, until the quarterback determined the rookie receiver was remarkably sure-handed — even though Clark wasn’t confident he’d make the roster.

“Looking around the team, you could tell that he was probably as good as there was on that team at that point,” Montana told The Times in January. “But he never ever unpacked his bags. Every time the [team executive assigned to informing players they were cut] was coming around, Dwight would always put his playbook on the bed so he could get out of there. Because he knew he was going to get cut. I was like, ‘You’re never going to get cut. I don’t know what’s wrong with you.’”

Clark would go on to have a nine-year NFL career, all with the 49ers, and holds spots in the club record books with the fourth-most catches (506), third-most yards (6,750), sixth-most touchdown receptions (48) and third in consecutive games with a reception (105).

In a cruel twist, it was Clark’s hands that gave him the first hint of his ALS. Three years ago, they began to lose strength.

“I couldn’t tear open a package of sugar all of a sudden,” he said. “Then it kept getting weaker.”

Eventually, his legs followed suit. He needed a walker to go short distances, then was confined to a motorized wheelchair. He withered from his playing weight of 242 pounds to a gaunt 155 before regaining a bit with the help of a feeding tube.

Fueled by ample anecdotal evidence, researchers continue to look for a definitive link between brain injuries and ALS. Clark’s staggering medical costs were offset by what he received from the NFL concussion settlement, and from the support of former 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo, who sent him to Japan where he could be treated with experimental drugs.

“There’s people coming up with stuff all the time,” Clark said in January at one of his many Tuesday lunches in Capitola, Calif., with various groupings of teammates, friends and reporters who covered him. “Somebody may stumble onto something. I don’t think it will be in time for me to use it.”

Born Jan. 8, 1957, in Kinston, N.C., Clark began his Clemson career as a safety and put up unremarkable numbers after switching to receiver. The 49ers discovered him by accident. Bill Walsh wanted to take a look at his roommate, quarterback Steve Fuller, and Clark picked up the phone when the legendary coach called. When Walsh asked Clark if he’d catch Fuller’s passes at a private workout, the receiver agreed.

“Dwight was like a brother to me,” former 49ers running back Roger Craig said Monday, speaking haltingly in an attempt to maintain his composure. “Taught me how to be a better receiver. He helped me a lot. He’s the most humble human being you’d ever want to meet, man. One of a kind.”

Clark is survived by his wife, Kelly, and three children from a previous marriage, daughter Casey and sons Riley and Mac. Information regarding services was not immediately known.

Follow Sam Farmer on Twitter @LATimesfarmer

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.