From the Archives: Odom comes to Clippers with an eventful past but basketball skills far beyond his 19 years

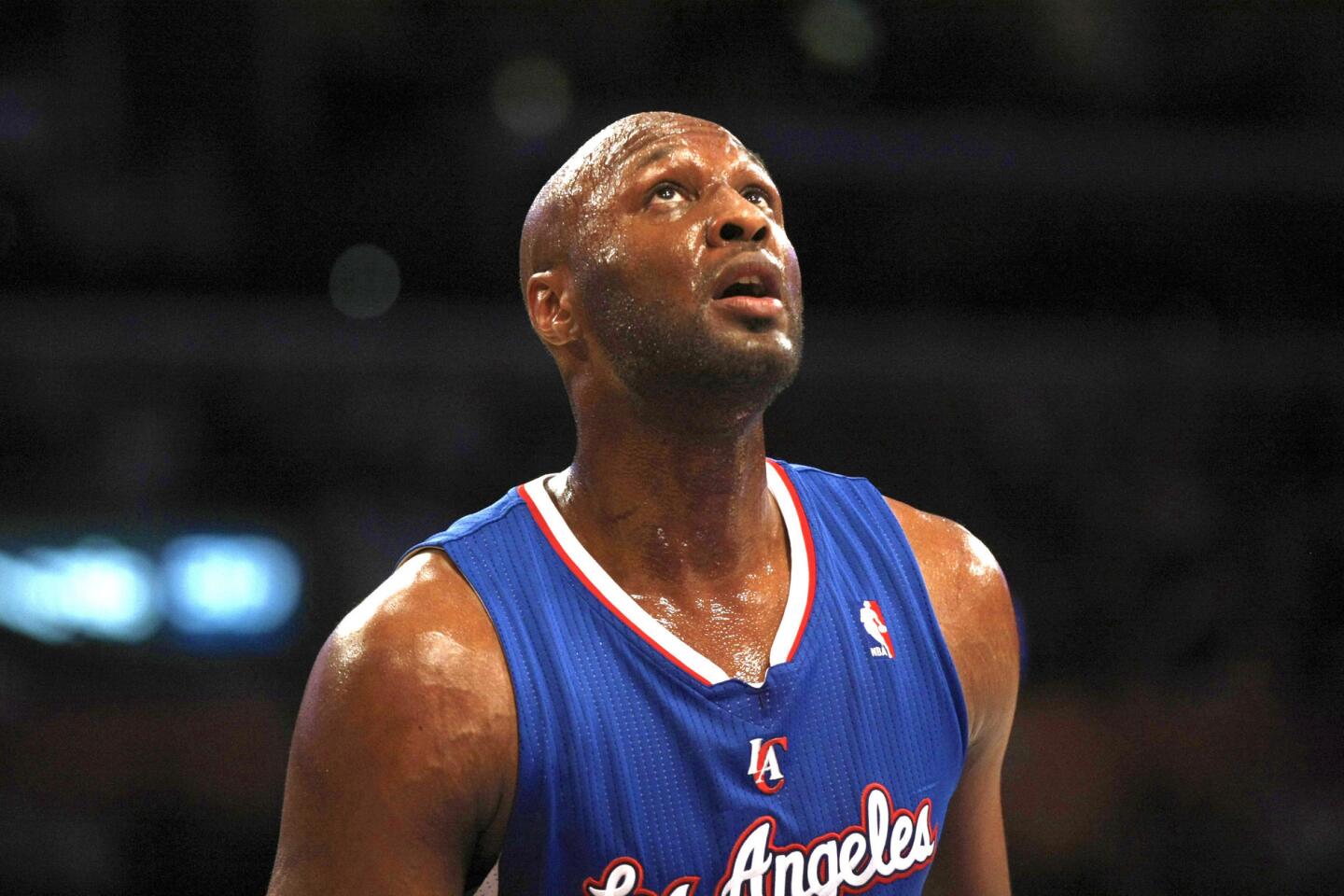

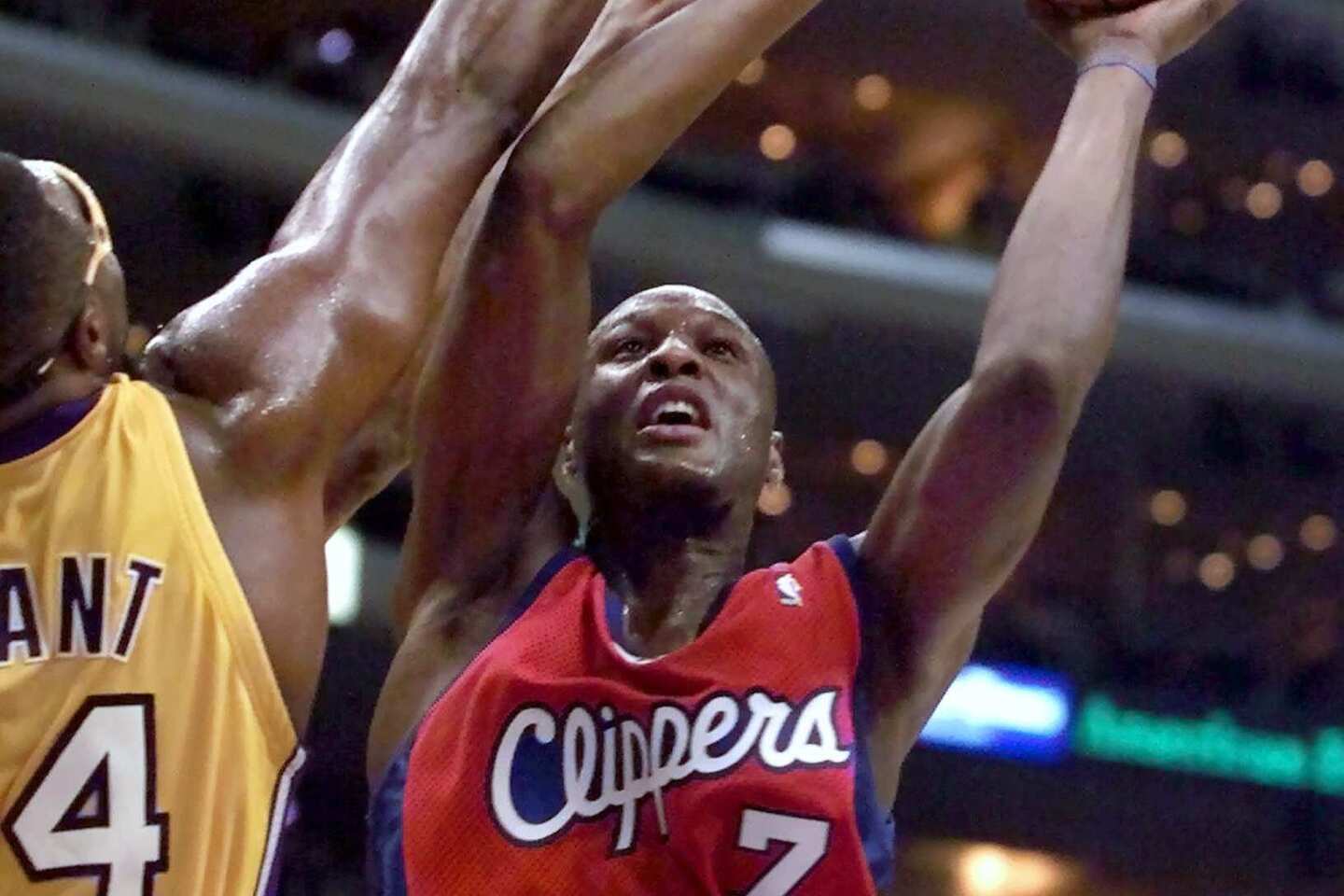

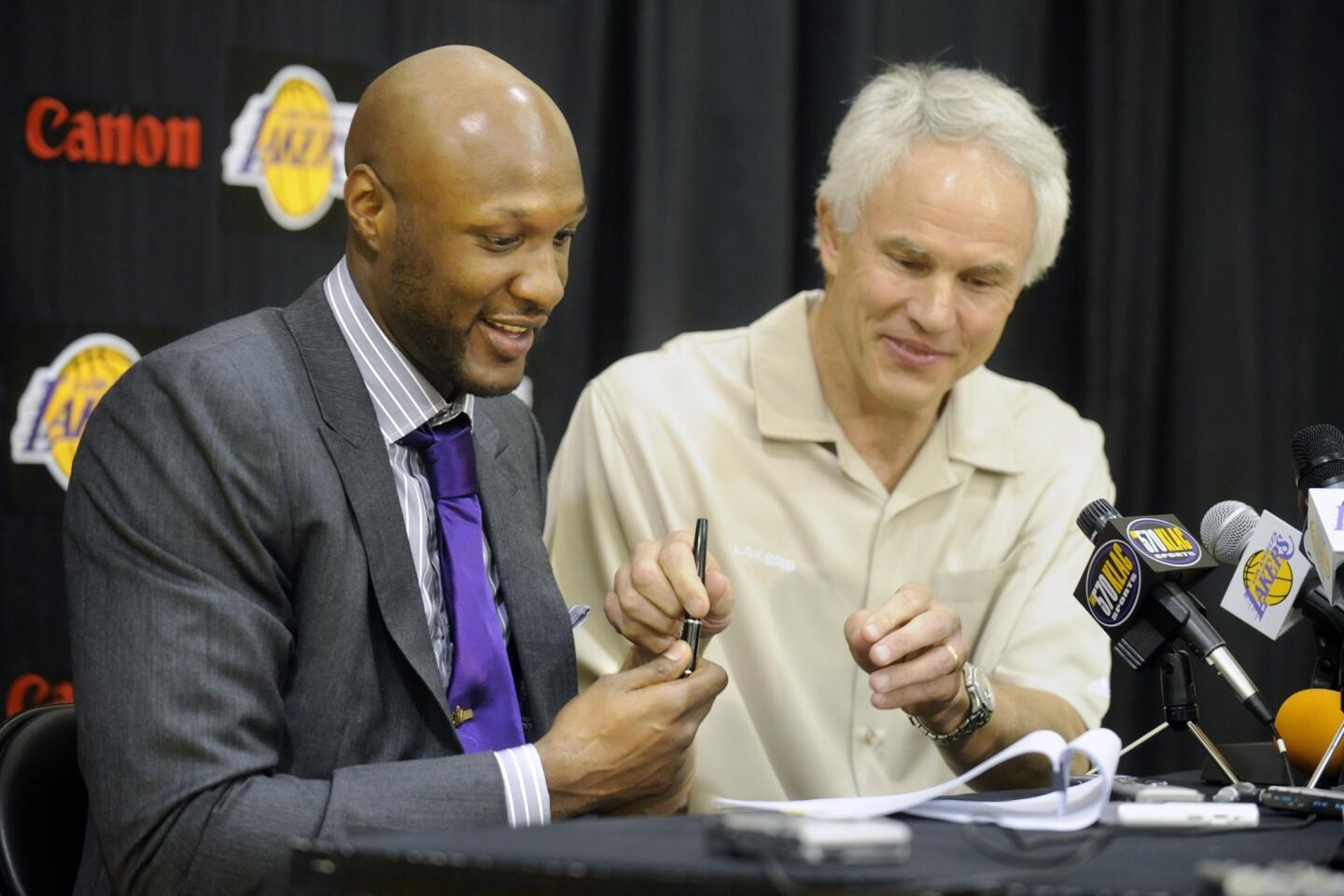

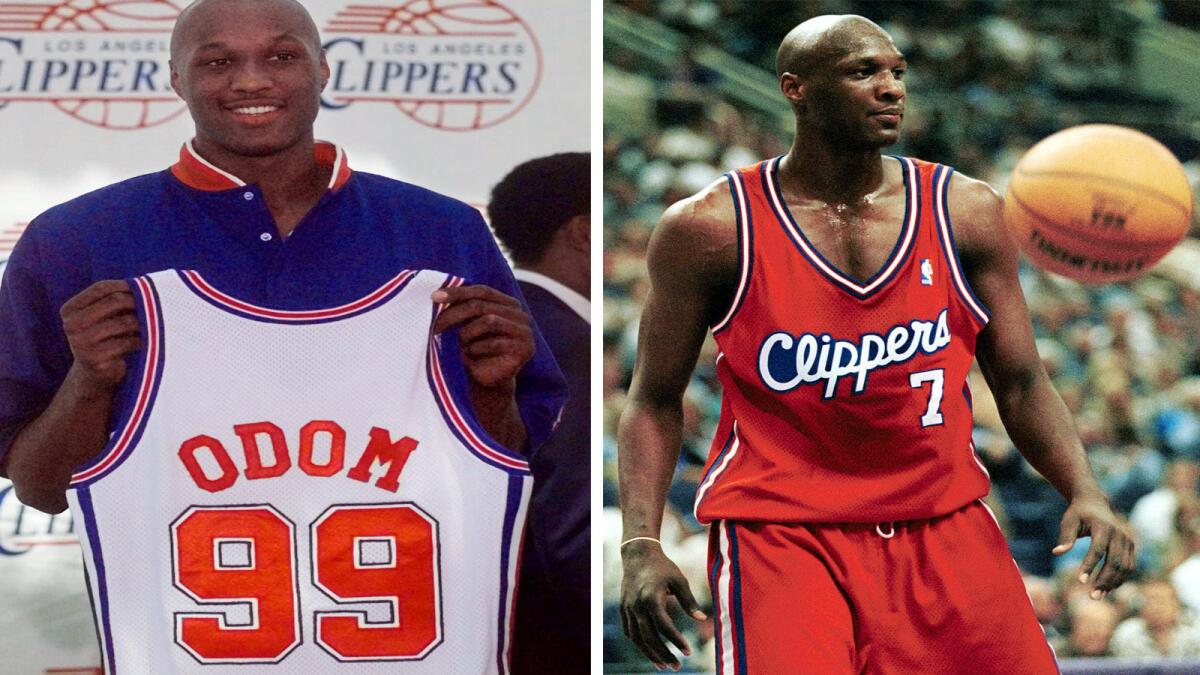

Left: Lamar Odom holds up a Los Angeles Clippers jersey with his name on it during a Clippers news conference July 1, 1999. Right: Rookie Odom is seen during a game against the Phoenix Suns on Oct. 19, 1999.

Reporting from New York and Las Vegas — Lamar Odom was found unconscious in a Las Vegas-area brothel on Tuesday and taken to a hospital. Authorities have not provided information on his condition. The following is a 1999 profile by The Times on the eve of Odom signing with the Clippers:

Lamar Odom’s mother died when he was 12 of colon cancer and, about the same time, his father temporarily dropped out of his life while dealing, Odom says, with a heroin addiction he has since kicked. Then Odom scored 36 points in the New York City Catholic League championship game as a sophomore and life got really hard.

“When he scored 36 points in the city championship game, it was the worst thing that could have happened to him,” says Tom Konchalski, who runs a high school basketball scouting service in the East and first heard of Odom when he was an eighth-grader in Queens.

“He became a national item and people started catering to him. He was made to feel like he was Superman. All the attention wasn’t healthy. His development was retarded. He would have been better off if he’d stayed hungry.”

He was made to feel like he was Superman. All the attention wasn’t healthy. His development was retarded. He would have been better off if he’d stayed hungry.

— Tom Konchalski, scout

Of course, Odom didn’t help himself with some of the choices he made. His instincts, which are almost always beyond question on the court, betrayed him off it, a pattern that would continue through three high schools during his senior year alone, two universities, three declarations--the first two rescinded upon further deliberation--for the NBA draft and two agents en route to Los Angeles and the Clippers, who made him the fourth player selected in June’s draft.

Shouldn’t he have been called by now for traveling?

But how many 15-year-olds would be prepared for the siege of AAU coaches, college recruiters, shoe company representatives and agents that he experienced at that age, especially if they didn’t have parents at home to counsel them? Odom had his elderly grandmother.

“Everyone tried to be his friend,” Konchalski says. “Not everyone had his best interests at heart.”

*

That could have been the first passage in a basketball diary about potential wasted. It might still become that. Odom was scheduled to fly from New York to Los Angeles on Wednesday night but had twice pushed back the date, telling at least one friend he didn’t want to play in Los Angeles or the NBA.

Or it could become the story of a young man who overcame his background, escaped from a tangled web not entirely of his own making and reached his dream of becoming a Hall of Fame player. He is only 19.

“Hopefully, I’ll be one of those special players,” Odom was saying last week, sitting in a conference room outside the office of his New York agent, Jeffrey Schwartz, who represents tennis players Pete Sampras and Marcelo Rios but, until now, no basketball players.

Odom, described by virtually everyone who knows him as a good kid and by himself as a “very good kid,” seemed enthusiastic, flashing his Magic Johnson-like smile, as he spoke about his future, saying he is eager to put his past in the past. As he spoke, he sported a red baseball cap that said, “Queens: School of Hard Knocks.”

“Every kid who gets into this game dreams about being in the NBA, about being the MVP, hitting the game-winning shot in Game 7 of the NBA finals,” he said. “My dream is to leave this game and say, ‘You know what? Lamar Odom is one of the top 50 players ever to play.’ Being a Hall of Fame basketball player, coming from where I came from, that would be really like mission accomplished.”

My dream is to leave this game and say, ‘You know what? Lamar Odom is one of the top 50 players ever to play.’

— Lamar Odom

The Clippers, who expect to sign him at their Sports Arena offices either today or Friday, are as excited about his prospects.

“Basketball-wise, for a kid his age, he’s really got a great feel for the game,” Clipper General Manager Elgin Baylor said of the 6-foot-9 Odom, who can play three positions and, with more strength, eventually could play all five.

“If you talk to everyone, it’s clear he was the best player in the draft.”

But not everyone is optimistic that Odom has come to the right team--or the right town--at the right time.

“I’m worried about Lamar,” said Gary Charles, who coached Odom during the summers of his high school years with an AAU team.

“The kid doesn’t want to be in the NBA. He wants to be in college. He’s not ready for this. The worst thing that could have happened to him was to be drafted by the L.A. Clippers.

“It’s L.A., and it’s the Clippers.”

A Model Search

Charles, 37, is a systems programmer for the Bank of New York, assigned to the bank’s Y2K project. He believes his association with Odom has prepared him well for a task with potentially catastrophic consequences.

Charles, the coach for the last 10 years of a successful AAU team, the Long Island Panthers, recruited Odom in the summer before his sophomore year at Christ the King High in Queens.

Charles said he had the blessing of Odom’s grandmother, Mildred Mercer, and aunt, JaNean Mercer, because he was “from the corporate world and dressed corporate-like. They wanted that to rub off on Lamar.”

He certainly believed he was a better role model than Odom’s father, Joe, who left home when Odom was 6. Before that time, Odom remembers his father fondly as someone who would come home from work at the post office and play catch with him in the yard of their South Ozone Park house. His later memories of his father were as a junkie.

“I guess that made me bitter,” Odom said. “I give him credit because he’s a warrior and he’s fought it off and now he has his life together. But his addiction hurt me, hurt our relationship. I had to see him like that once or twice and that’s what hurts the most.”

By the winter of his sophomore year, when he led Christ the King to the Catholic League City Championship with 36 points against St. Raymond’s at the Fordham University gym, Odom had grown to 6-7 and was, Charles said, “the most perceptive basketball player I had ever met.”

Konchalski said that even as a sophomore Odom had a “Phi Beta Kappa understanding of the game.”

But he was no scholar in the classroom.

“He thought the rules didn’t apply to him,” Konchalski said. “His grades started to suffer. He didn’t want to learn. He’d show up for class, but he wouldn’t do his homework.”

When Odom left Christ the King in October of his senior year, seeking--at Charles’ behest--a more forgiving academic atmosphere at Redemption Christian Academy in Troy, N.Y., he stood 312th in a class of 334.

Five months later, Odom transferred again. He was still struggling with his grades. And he was convinced that Redemption cared about him only because he might strike it rich as a basketball player.

He went this time to St. Thomas Aquinas in New Britain, Conn., where one of Charles’ best friends, Jerry DeGregorio, was the head coach and agreed to let Odom live with his family for the remainder of his senior year.

Basketball followers assumed Odom would bypass college and enter the NBA draft, as the previous season’s consensus No. 1 high school player, Kobe Bryant, had done.

They assumed wrong, Charles said. He said Odom had his mind set for some time on playing for Kentucky, developing second thoughts only after it appeared that the Wildcat coach, Rick Pitino, would be lured away by the Boston Celtics.

What Charles didn’t say is that several other universities, including UCLA, dropped out of the recruiting when they realized Odom wouldn’t have the grades to enroll.

On April 6, 1997, while at Magic Johnson’s Roundball Classic for high school all-stars in Auburn Hills, Mich., Odom called a news conference for noon to announce his decision between Kentucky and Nevada Las Vegas.

“At five of 12, he still hadn’t made up his mind,” Charles said.

Odom carried baseball caps from both universities in his duffel bag.

The cap he wore upon announcing his choice was from UNLV.

“It was the worst decision he could have made,” Charles said. “Sin City.”

No Vegas Vacation

The Rebels’ recruitment of Odom, Charles suspects, began in the summer between Odom’s sophomore and junior years. The Long Island Panthers went to Las Vegas for the Big Time Tournament without Odom, who was in summer school, but his aunt, JaNean, accompanied the team, Charles said.

Charles said he believes there was contact that summer between JaNean and a UNLV booster, David Chapman, 37, a Las Vegas dentist who has attended Rebel games for years.

Neither Chapman nor JaNean would agree to an interview. Chapman’s lawyer, James Chrisman, said his client doesn’t want to talk to reporters until he has been interviewed by NCAA officials, who are investigating the nature and extent of Chapman’s relationship with Odom, in particular his role--if any--in UNLV’s recruitment of the player.

NCAA investigators declined to comment. Calls to UNLV were referred to associate athletic director Jerry Koloski, who also declined to comment.

A source familiar with Chapman’s version of events, however, said the aunt made the initial contact with Chapman at a summer-league game--where she mistook the dentist for UNLV Coach Bill Bayno.

Charles said he is certain that Chapman met with Odom the next summer, while the Panthers were in Long Beach for the Izzy Washington Slam-N-Jam Classic and in Las Vegas for the Big Time Tournament--because he recalls calling Bayno to complain. Bayno declined comment for this story.

Odom said he doesn’t remember meeting Chapman until he arrived at UNLV in the summer of ’97 to take a physical education class required for his high school diploma.

That July, Sports Illustrated published an article suggesting that Odom cheated on his ACT test. Although that was never proved, and Odom continues to deny it, he said he was told the next day by a UNLV official that he wouldn’t be allowed to enroll in the fall.

“There was a knock at the door,” he said. “It wasn’t even a coach. It was like an administrative assistant. He says, ‘A lot of people are talking. Coach Bayno doesn’t know what to do. The president is really scared. They think it’s better if you just leave.’

“A couple of days after that, I was out with some friends and I made one of the stupidest mistakes of my life. I got in trouble for soliciting a prostitute. That only made matters 10 times worse. When that happened, I really looked like some kind of a dumb kid. I guess it was meant to happen because it let me know who my friends were.”

Among them, he said, was Chapman.

“You know when he really befriended me, after they told me I had to leave and the incident happened,” Odom said. “That’s how I knew he was a real person. When I was a cancer and everyone wanted to stay away from me, he was the only one who reached out to help.”

When Odom’s daughter, Destiny, was born last year, he named Chapman the godfather.

Professional Pressure

Another friend, Odom said, was DeGregorio.

He had been hired from St. Thomas Aquinas by Jim Harrick to become an assistant at Rhode Island and began recruiting Odom to rejoin him in Kingston, R.I.

“One year, I’m the best player in the country and choosing between Kentucky, UCLA, UConn and UNLV,” Odom told Charles. “The next year, I’m choosing between Hofstra and Rhode Island.”

Odom chose Rhode Island, sat out a year while getting his transcript in order and then finally was allowed to begin his freshman season.

He won the Rams’ first game last season, against Texas Christian, with a last-second shot, and then did it again in the championship game of the Atlantic 10 tournament, against Temple, as Rhode Island advanced to the NCAA tournament before losing in the first round in overtime to North Carolina Charlotte. In 28 games, he averaged 17.5 points, 9.4 rebounds and 3.6 assists.

He might not have been the best player in the country, but he showed the most potential and NBA scouts predicted he would be the first player chosen if he declared for the draft.

He went to visit Charles at his Long Island home in late March and asked for advice.

“I said, ‘Son, follow your heart. You can’t make a bad decision. Whichever way you go, I have your back,’ ” Charles said.

Charles also said Odom told him that Chapman was pressuring him to turn pro and sign a management contract with a company, R&D Sports Management, run by Chapman and a 57-year-old Las Vegas engineer, Roger M. Peltyn.

State records indicate the firm was incorporated in August 1997, during the brief period Odom was living in Las Vegas. Its only current client, Peltyn said, is Odom.

“I called Chapman and cursed him,” Charles said. “I told him that he had no business putting that kind of pressure on Lamar. I told him that I was going to kick his ass.”

In response, he said Chapman accused him of also pressuring Odom to declare for the draft and trying to steer him to another agent, which Charles denies.

Charles said he has spoken to neither Chapman nor Odom since. Charles said, however, that he heard through a friend of Odom’s that his aunt, JaNean, went to Odom crying, begging him to turn pro and sign the management deal.

In late April or early May, Peltyn said, Odom signed the management contract. Peltyn declined to divulge details: “That’s privileged.”

Asked if Odom had gotten money from him, from Chapman or from R&D at any time before signing the management contract, Peltyn replied: “Nothing. We’re not that stupid.”

Odom also hired a New York agent, Jeff Klein, saying he had been introduced to him through Chapman.

Klein advised Odom to fly to Vancouver for a workout with the Grizzlies, who had the second pick in the draft.

“He prepared for it like you’d prepare for an exam,” Klein said. “He blew them away, he was so good.”

Then Odom disappeared.

Trying Times

“He blew off his other tryouts against my advice,” Klein said. “People around him started to say things and do things. There are a whole myriad of inconsistencies.”

Klein let Odom go. Neither will disclose details.

“He’s a good kid and I like him,” Klein said. “There aren’t four of my [attorney] brethren who would have fired him because you can make a lot of money off him. I had only one idea. It was really simple, to help him. But the bottom line is that I couldn’t help him if he wouldn’t return my phone calls.”

It was no big deal, Odom said.

“People get divorced,” he said. “Why can’t I get another lawyer?”

But it was a big deal to NBA teams when he didn’t show for the scouting combine in Chicago. Then he missed a scheduled workout in Charlotte with the Hornets, then another in Chicago with the Bulls.

“At the time I declared for the draft, I had a chance to be a top-five pick and I really wanted this,” Odom said.

“But after going through the business part and meeting Jeff Klein and not having a 100% feeling about who I was dealing with financially, the business part turned me off about the NBA.

“If you’re a kid and you don’t have anybody guiding you, holding your hand, there’s no way possible you can understand what is at stake, how much money is involved, how many people want your money. It was scary to me, honestly. I was at the point where I told myself, ‘All I’ve got is you.’ I decided to go back to school.”

If you’re a kid and you don’t have anybody guiding you, holding your hand, there’s no way possible you can understand what is at stake, how much money is involved...

— Odom

He called DeGregorio, now the head coach at Rhode Island, and asked if he could return to the Rams for his sophomore year. Officials there told him it was impossible because he had by then signed with Klein.

“I was trying to make a statement and let everyone know where my head was at,” Odom said. “It kinda backfired. It led everyone to believe I was a rebel who wasn’t showing up because I had problems.

“Sorry if I offended anybody in that process. But I was a young man going through a lot. I handled it the way I thought it needed to be handled. I guess it wasn’t the best way.”

Resigned to entering the NBA, Odom sought advice from DeGregorio. The Rhode Island coach arranged for him to work out in Kingston, four days before the draft, for the Clippers, Bulls, Raptors and Heat. He then boarded a plane and went to Miami to work out for Pat Riley. On the night before the draft, he flew to Chicago and met for 5 1/2 hours with the Bulls, who had the No. 1 pick.

During this period, Odom was also actively exploring marketing possibilities with Loud Records, home of such rap stars as Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep and Big Punisher. Ultimately, he and the company decided the time wasn’t right to do business, a Loud executive said, adding, “I just think there were too many people pulling at him from too many directions.”

Sources close to the Bulls said that they were impressed with Odom’s talent and personality but didn’t trust him, opting for the safer Elton Brand of Duke with the first pick. Vancouver thought Maryland’s Steve Francis was a good backcourt fit with point guard Mike Bibby and took him at No. 2. Charlotte, drafting third, wanted a point guard and took UCLA’s Baron Davis.

That left Odom for the Clippers. Baylor said he was wary, but the Clippers checked him out thoroughly and found no evidence of nefarious behavior.

Charles said he almost cried when the Clippers selected Odom:

“I don’t know what’s going to happen to him in L.A. Now you’re telling me he hired a tennis agent. Are you kidding me? What does he know about basketball?

“Lamar has the potential to be another Magic. He’s that good. But he can’t reach his potential without strong people around him.”

Reality Check

Odom vividly remembers the night he scored 36 points to lead Christ the King to the city Catholic League championship. From that point on, basketball was never again a game to him.

“Since the 10th grade, a lot of the people I’ve come across are no good,” he said. “They’re just trying to help themselves.

“It’s like I became a sports object. People want to be in control of me, like they want to own me. The whole basketball thing kills me when I see grown men fighting over kids. I don’t understand that to this day.

“Someone like me needs realness, which I don’t come across too much. I’m always bumping into someone with an agenda.”

Asked if he believes anyone in his life is real, he said he could be sure of only two persons, his grandmother and his 11-month-old daughter.

“You know what, though? Except for the death of my mother, I wouldn’t change a thing that’s happened to me. The next best basketball player might come from South Ozone, Queens. It might be my mission to tell him, ‘This is the way it is in this whole crazy basketball world, these people are going to come after you and this is what you have to do.’

“If I can warn young players to stay away from the people I should have stayed away from, it was all worth it.”

Harvey reported from New York, Abrahamson from Las Vegas.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.