Curacao an island unto itself when it comes to producing big-league ballplayers

Reporting from WILLEMSTAD, Curacao — A cruise ship rises into view just beyond the left-field foul line of Curacao’s largest ballpark, and a row of tall, thin palm trees provide little shade to keep the diamond’s rocky dirt infield from baking in the midday sun. This simple tableau captures the shifting fortunes of the tiny Dutch protectorate that gained its independence just seven years ago.

Tourism remains a pillar of the economy on the scenic island, which last year was named the top cruise destination of the southern Caribbean. The major export: baseball players, including All-Star closer Kenley Jansen of the Dodgers and Gold Glove-winning shortstop Andrelton Simmons of the Angels.

Despite a population of just 160,000 — less than the city of Santa Clarita — Curacao has sent 14 players to the big leagues since 2000, the most per capita of any country. Another 25 players were on minor league rosters for opening day last spring.

Luis Marquez, a Latin American scouting supervisor for the Dodgers, says a simple formula has made the island the world’s most fertile producer of baseball talent:

“They have the tools. They play every weekend during the whole year. Most important, I think, is they’re pretty smart. Everything together, that’s why they’re pretty good players,” Marquez said.

Five of the six players from Curacao who appeared in the major leagues last season had not turned 30. Jansen, who turned 30 on the next-to-last day of the regular season, and Baltimore’s Jonathan Schoop, 26, played in the All-Star Game. Simmons, 28, won his third Gold Glove.

Marquez, who grew up playing baseball in Venezuela, just 40 miles to the south, said he didn’t know baseball was played in Curacao until he became a scout with the New York Mets a decade ago.

“They’re really good athletes,” he said. “It took MLB a while to discover that.”

A speck on the map in the Lesser Antilles, Curacao covers just 171 square miles, making it smaller than San Jose. The island nation’s capital, Willemstad, was founded by the Dutch West India Company in the early 17th century, its natural harbor making an ideal port for commerce, shipping — and piracy.

Willemstad became a lucrative center of the Atlantic slave trade, a stopping point for ships laden with slaves destined for the Caribbean and South America. As a result, the majority of Curacaoans are of African descent.

Baseball has been played on Curacao for more than 80 years, reportedly dating to a game between Dominican laborers and Venezuelan fruit sellers. But the island didn’t send anyone to the big leagues until 1989, when the New York Yankees called up Hensley Meulens, who had been signed as an amateur free agent four years earlier.

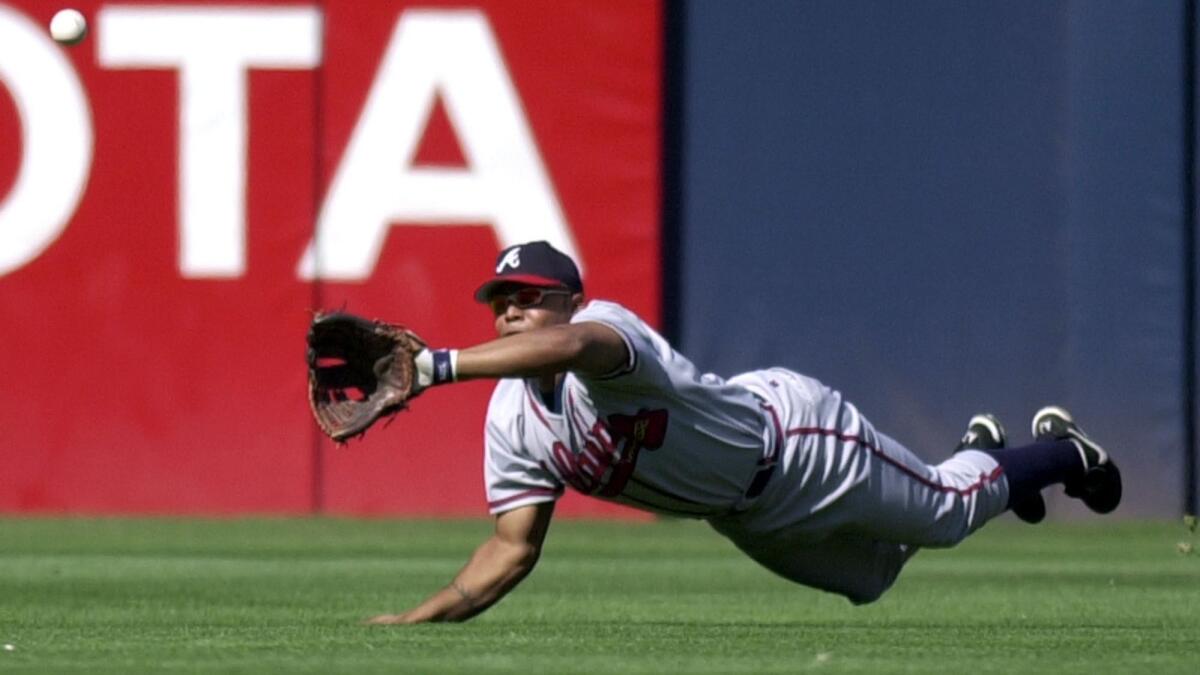

Meulens, now the bench coach for the San Francisco Giants, had a short, undistinguished playing career with three teams. But he helped open the way for Andruw Jones, who debuted as a teenager with the Atlanta Braves in 1996 and went on to hit 434 home runs, win 10 Gold Gloves and make five All-Star teams.

Jones’ success in turn led to a baseball boom on the island.

“The first thing I remember is watching him play on TV,” Simmons, the Angels infielder, said. “Everybody wanted to be like Andruw Jones. That was a big thing for me and I think for a lot of kids from my generation.”

When Jones signed with the Braves in 1993, there were about 200 youths playing organized baseball in Curacao. At the time of his major league debut, three years later, there were nearly 1,000.

The surge in popularity led to the event that really put the tiny island on the baseball map: qualifying for the Little League World Series.

In 2001, Curacao began a nine-year run of appearances in the youth baseball championship held annually in Williamsport, Pa. In 2004, with a roster that included future big-leaguers Schoop and Jurickson Profar, the island representative defeated Thousand Oaks to become the first international champion from a Caribbean nation in the event’s history.

“It boomed after Curacao started going to the Little League World Series,” said Fermin Coronel, a former Dutch naval officer who coaches and works part time as a scout. “That was the switch.”

The change was immediate, said Darren Dacosta Gomez, another coach.

“Every city has a team,” he said. “Every neighborhood has a baseball field.”

Those fields are largely rock-strewn dirt lots, but they are ideal for sharpening reflexes and building toughness.

As a boy, Profar, the Texas Rangers’ shortstop, was struck in the face by a bad-hop grounder, knocking out a tooth and sending him to the hospital. When he returned to his position a few days later, he found the tooth lying in the dirt and rocks.

“We didn’t have the prettiest fields, so our hands have to be kind of sharp and our footwork has to be sharp because you have to get a good hop,” said the slick-fielding Simmons. “That’s why you see a lot of infielders from Curacao.”

Simmons grew up playing with Jansen, New York Yankees shortstop Didi Gregorius and former Colorado Rockies pitcher Jair Jurrjens. Official games were infrequent, though Simmons remembers fiercely competitive practices each week. “The guys you’re around and the way that we practiced, really intense,” Simmons recalled. “We wanted to be really good.”

As talented as some young locals players are, “when they sign [with] professional baseball, they still have a lot to learn, said Marquez, the Dodgers’ scout whose organization has signed several players from Curacao in the last two years. The islanders have some built-in advantages there, too. The nation offers one of the highest standards of living in the Caribbean, and state-funded education is compulsory from age 4 to 18. The country has three official languages — Dutch, English and Papiamento, a Portuguese-based Creole language. Many people speak Spanish as well, learned largely by listening to radio and TV broadcasts from Venezuela.

As a result, the Curacao players come to the U.S. healthy, educated and multilingual, which typically makes the adjustment easier than it is for other foreign-born prospects.

This winter, Major League Baseball invested in the region by opening a program designed to provide players ages 13 to 18 with nine hours of instruction per week from major- and minor-league coaches.

Coronel, who spends many humid afternoons smacking grounders through the dirt for as many as four dozen young ballplayers at a time, is hoping even more resources will be provided by the players who left the island and struck it rich in the big leagues.

Jansen, who signed a five-year, $80-million contract before last season, has already stepped up. Several teams in Curacao wear uniforms and caps he provided. Others swing bats he paid for, catch with gloves he shipped over, or throw the Rawlings baseballs his brothers regularly collect from the local FedEx office.

“It’s not an obligation. But if you feel you need to help, do it,” said Jansen’s oldest brother Verney, 38, who turned down a contract with the Yankees at a time when the trip between the island and professional baseball was far-less traveled. “The thing is, we’ve been in that situation and we know how hard it is.

“We want a field with grass and everything. Imagine if we had the structure like the U.S. has with all this talent.

“If we had that we’d have like 30, 40 guys in the majors. Not 15.”

Follow Kevin Baxter on Twitter @kbaxter11

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.