Kobe Bryant’s stolen high school jersey returned for ceremony

ARDMORE, Pa. — Kobe Bryant’s high school jersey spent more time in China of late than it did hanging on the wall of the gym named in honor of the school’s career leading scorer.

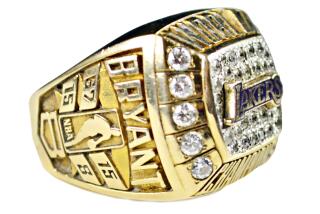

Bryant’s retired No. 33 jersey was stolen in 2017 from the campus of Lower Merion High School and eventually bought by a collector in China. Suspicious that the jersey had been stolen, the Kobe collector contacted the school and helped return the keepsake to suburban Philadelphia, a process already underway before Bryant was killed in a helicopter crash.

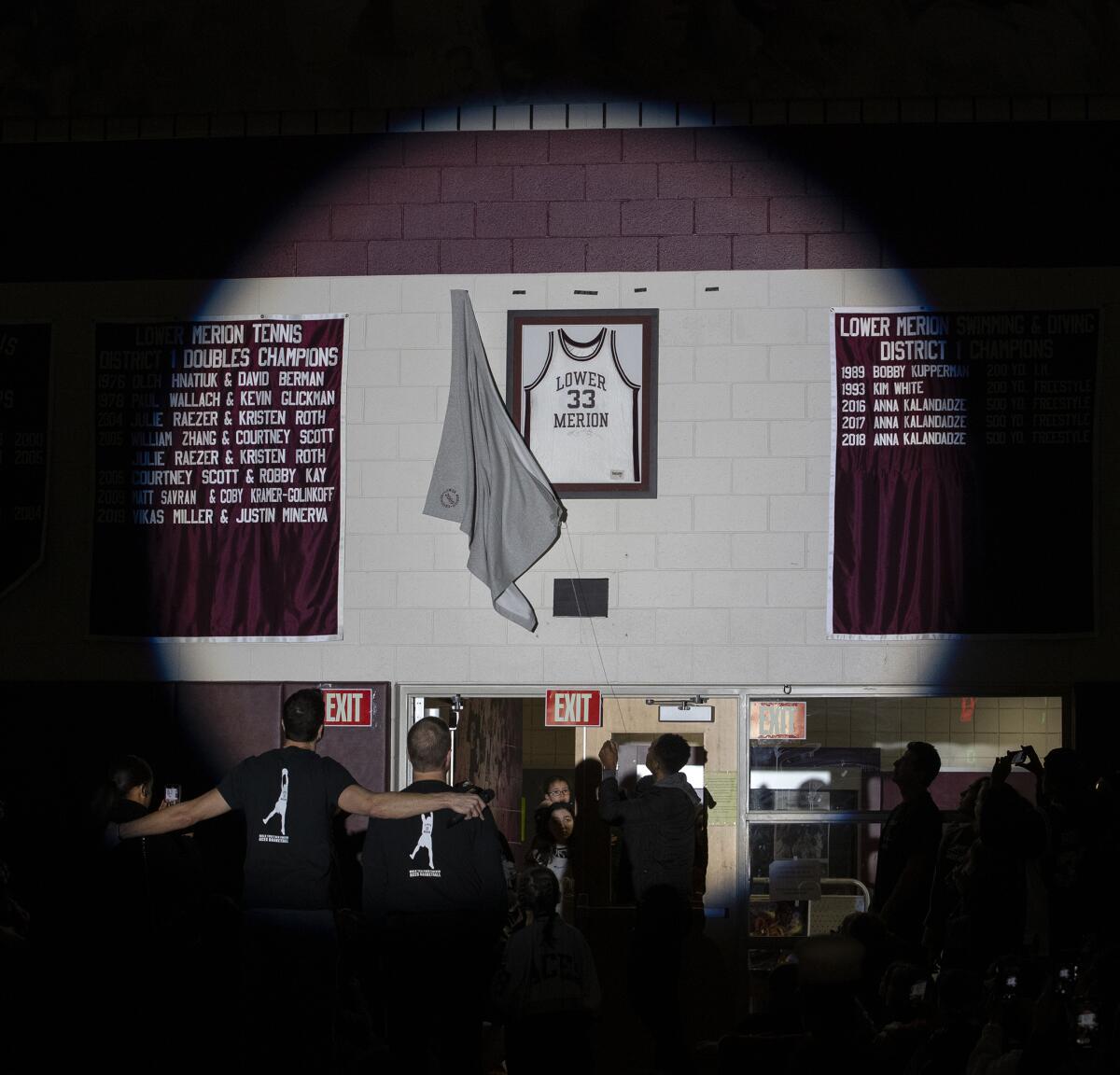

On Saturday, the uniform was at last back where it belonged — unveiled under a spotlight by Bryant’s cousin, his old high school coach, and a former teammate at Bryant Gymnasium.

“Good timing,” Lower Merion coach Gregg Downer said. “That was kind of an iconic moment when the spotlight went on that jersey. It was just tremendous. It was major irony, almost, how we’ve been waiting for that jersey for a long time. For a long time we didn’t know where it was. To have it back, it’s a fitting ending to a tough week.”

Outside of Los Angeles, no place was as connected with Bryant as Lower Merion. At a tribute Friday night in L.A., the entire Lakers lineup was introduced the same way: “From Lower Merion High School, No. 8, Kobe Bryant.” Golfer Justin Thomas wore a Bryant No. 33 LM jersey at a tournament. The Sixers had the 33 logo on the court this week at their first home game since Bryant was killed.

While NBA teams spent the ensuing days holding observances for Bryant, Lower Merion finally played its first home game and celebrated the biggest star ever to play for the Aces. Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven others who were killed were all remembered in the pregame ceremony.

“Because of Kobe, Lower Merion High School is known all over the globe,” principal Sean Hughes told the crowd. “Despite his international fame, Kobe kept very close to our hearts. He returned here to meet with beloved [English teachers] and, of course, coach Downer. He helped make this gym the wonderful facility it is. He was a strong supporter, not only of our basketball teams, but all of Aces Nation.”

The gym was packed to at least the 1,600 capacity, and students wore black T-shirts that read “The Heartbeat of Aces Nation” with a 33 inside an ace. Sixers coach Brett Brown’s son plays on the team, connections far removed from the A-listers who packed Staples Center a night earlier in a stirring ceremony. At Lower Merion, a former student sang the national anthem. A teacher unveiled a portrait she had painted of Bryant. School administrators gave speeches.

Once the ball tipped, it was business as usual, without the 24-second shot clock and eight-second backcourt violations NBA teams have been performing to salute Bryant’s two pro uniform numbers. Lower Merion did hold 33 seconds of silence, and former teammates (and Bryant’s cousin John Cox) gathered in a mournful circle at midcourt.

In some ways, the Aces’ 42-37 overtime win over Souderton seemed as normal as Bryant’s presence in the gym. He’s just a name between Carly Brown and Mike Venafra on a banner listing the Aces’ career 1,000-point scorers. A photo of Bryant holding the 1996 Class AAAA state championship trophy was on the wall, blending in with dozens of other great players and teams from program history.

There was even some levity during video highlights of his playing career when Bryant was shown reminiscing about his high school days, saying, “The first year I got there, we went like 4 and 40 or something. We were terrible.”

Cirilo Perez drove nearly 2½ hours from Heightsville, Md., to pay his respects to Bryant at the memorial in front of the gym. He didn’t have a ticket to the game; he simply wanted to be part of the day devoted to his favorite player. Perez wore a Bryant jersey and left his Lakers hat at the scene, which was loaded with basketballs, cards and signs left from Bryant fans near and far.

“He put in the work and brought that blue-collar mentality that a lot of people connect with, not only here, but around the world,” Perez said. “He found a way to connect.”

Carter Knight, an assistant coach at Souderton, gathered the Indians for a team photo at the site.

“It’s real right now,” Knight said. “We’ve been talking about the ‘Mamba Mentality’ since the start of the season, so it’s crazy that we’re here today. We’ve been harping on that the entire season, that mental toughness and what Kobe brought and what he stands for.”

Bryant’s former guidance counselor attended the game, recalling how his Toyota Land Cruiser was often parked in the teachers’ lot long before the school day started.

“His smile was the greatest thing I remember,” Frank Hartwell said. “He was just an inspiration to so many; it wasn’t all about himself. He was here before school every day working on his skills. He wasn’t just in here shooting, he was working on his moves.”

Hartwell said Bryant even talked to him as he considered his biggest move — making the jump to the NBA straight from Lower Merion.

“I gave him the pros and cons, but I told him, ‘It’s up to you.’ I think he made the right decision,” Hartwell said.

Bryant made the right call, starting with a Mamba Mentality that took hold in Lower Merion long before it became a marketing catchphrase.

“It was a chase of excellence like I’ve never seen,” Downer said.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.