Lakers star Anthony Davis took root from humble beginnings in Chicago

CHICAGO — It’s not really a parking lot, this cracked blacktop underneath a row of cars. White lines denote a basketball court, and a sedan is parked on top of the blue painted area in front of the hoop.

A man rushes out the back of Perspectives Charter School to tell another they have to get these cars out of there. This is a space for kids to play.

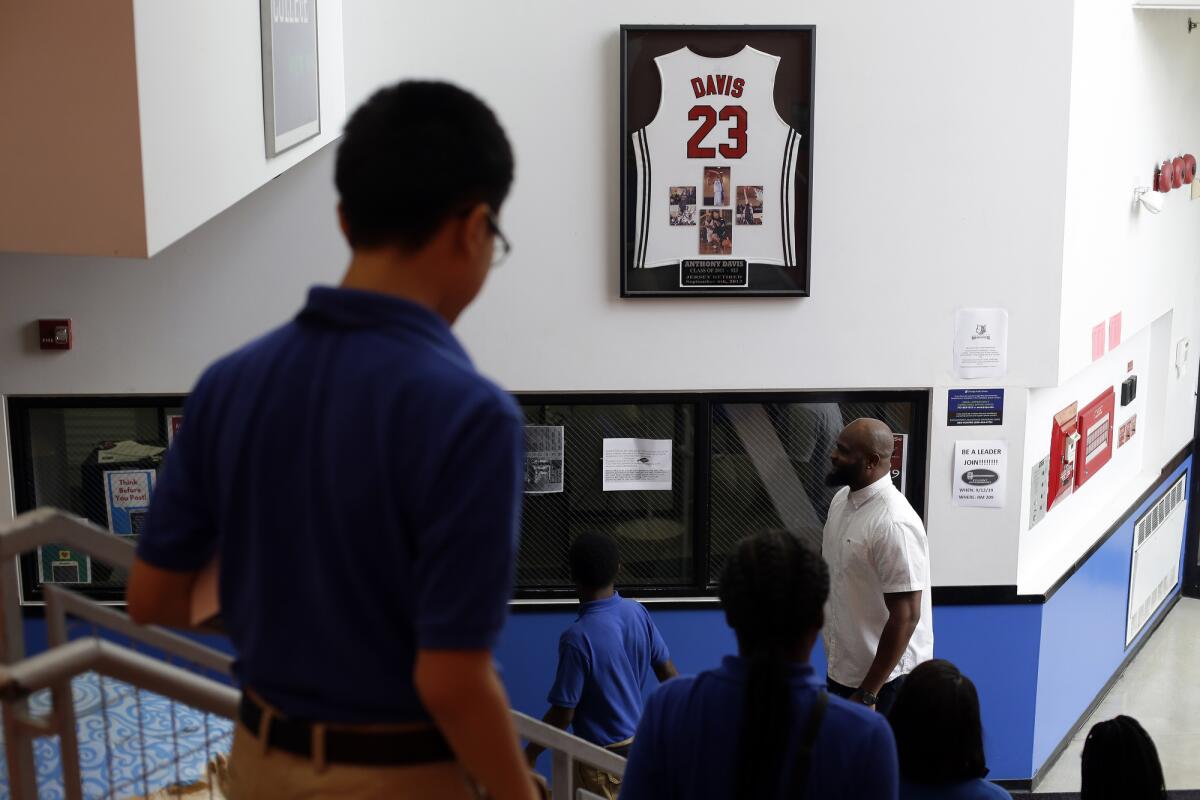

Painted on the ground a few yards from them is a remnant of the reason this humble recreation area exists at all. It’s a white jersey with blue lettering and the number 23 — the jersey Anthony Davis wore when he was a student at this tiny school. In his day, they’d roll out a portable rim for pickup games and cover the back of it with enough rocks to withstand a dunk from the only student who could manage one.

Davis partnered with a sponsor six years ago to donate this court, and he’s told people at the school he wants to build them a real gym someday.

Davis is now a superstar in a town of superstars, giving hope to a once-glittering Lakers franchise that he and LeBron James are expected to save. But his path to stardom began in a place that didn’t make stars, a school where Davis’ transcendent ability swept everyone into a whirlwind impossible to forget.

He never dreamed then that he’d be where he is now.

“From a small school, a high school in Chicago, coming where I come from in Chicago, is something that’s surreal for me,” Davis said, “and it’s exciting and I never take it for granted.”

It began where he played basketball in the most unconventional of spaces.

::

Tavia Frazier placed a sandwich board outside the gothic facade of the Second Presbyterian Church on an August morning. She gives tours here, teaching visitors about its history, about the efforts to restore the dulled stained-glass Tiffany windows, and how a fire 119 years ago changed the design aesthetic.

She’s never heard of Anthony Davis.

“He got his start here?” she asks.

Not quite, but there’s a gym in the back of this church that served as a practice space for Perspectives in Davis’ early days of attending middle school. Today, the place has blue painted walls and a hardwood floor. A collection of basketballs — one of them is a dusty purple and gold — sits behind the base of the stanchion under the hoop. There’s also a bright red ball about the same size — these days, Perspectives uses this gym for dodgeball.

The Joslin Campus of Perspectives that Davis attended, seven miles north of his home on Chicago’s South Side, had 325 students from sixth through 12th grades.

“Kids don’t necessarily have to watch their back every five minutes walking down the street,” said Tiray Jackson, the athletic director for Perspectives Charter Schools, which has five campuses. “They feel safe. It feels like a safer environment. Ninety-five percent of our kids are poverty stricken. They come from places like — I think Anthony grew up in the Englewood area.”

Englewood’s poverty rate is twice that of Chicago as a whole, according to the Census Bureau. It also has a higher concentration of crime than its surrounding neighborhoods, according to the city of Chicago’s published data. The Chicago Tribune’s data list at least two dozen homicides this year in the blocks surrounding Davis’ childhood home.

“There were other schools that were closer to him that he definitely could have went to,” said Cortez Hale, Davis’ high school coach. “But his dad was like, ‘I’m not sending my kid there. Those areas, it’s not safe.’ ”

A visit to the home where the Davis family lived reveals a yellow house with multiple stories. Ornate columns with peeling white paint hold up the front porch. The gutter is falling from the roof over the entry, and the backyard is overgrown with foliage.

This afternoon, a handful of people sat outside — three men playing dominoes at a folding table and a woman resting in a worn upholstered chair. They remembered when Davis lived here.

He was a lanky high school kid who sometimes wondered if the basketball world would ever notice him.

Hale said Davis “would go to games and say, ‘No coaches are coming to see us because we’re a little school,’ or ‘How come we can’t play this type of team so people will come see me play?’ ”

Even though they partnered with other Perspectives campuses around the city, they had trouble putting together a basketball team.

“I did find it weird at first,” Davis said years ago. “I mean, what school doesn’t have a gym? But we worked with what we had.”

None of his teammates spent all four years of high school on the basketball team. During his sophomore year, the team began with 15 players and ended with six. Hale remembers trying to recruit other top players to Perspectives but says the school’s academic requirements prevented that.

Still, Davis stayed.

In the summer of 2010, Davis played in an AAU showcase called Peach Jam, which altered the course of his career.

“Literally, come August, he hadn’t played a high school game since [the spring], and we come back to school and he’s the No. 1 high school basketball player,” recalls Vinay Mullick, who was then the athletic director at Perspectives.

That meant schools from all over the Midwest wanted to schedule games. Nike sent the team uniforms. The Basketball Hall of Fame called. Reporters wanted to cover the games, which meant Mullick had to figure out how to create a press row in the Illinois Institute of Technology gym the school used for practices and home games.

Perspectives played on ESPNU against Chicago public school powerhouse Whitney Young, a team with starters headed for Ohio State and North Carolina State and a freshman named Jahlil Okafor coming off the bench. Okafor went on to become the third overall pick in the NBA draft in 2015.

Davis was the only Division I prospect on his team.

“Mentally, physically and fundamentally, as a team [we were] not prepared for the exposure we would get from him,” said Manuel Whitfield, who was a year younger than Davis and now works for the mayor of Chicago. “He was prepared for it because he … worked hard for those things.”

Most of the team was playing basketball as a recreational after-school activity. They lost by wide margins to some of the best teams in the country.

Seeing the toll it took, Hale would tell them: “You guys know what’s going on right? You’re playing with the No. 1 kid in the country. This is something that you’ll never forget. This is a once-in-a-lifetime deal.”

They rode planes for the first time in their lives. For bus rides, Davis sometimes showed up wearing a gigantic blue Snuggie.

On campus, Davis played dominoes during lunch in Jackson’s office. He played pickup games with his friends. There was the occasional autograph request, but the school was so small his classmates didn’t really see him as a superstar.

“The kids always knew him as Anthony, as Fatman,” says Jonathan Daniels, a college counselor at Perspectives. Davis was a fat baby, which led to the nickname. “They were a real close-knit group of young people. They treated each other like family.”

Davis’ twin sister, Antoinette, and their older sister, Iesha, attended Perspectives as well. Their parents attended pretty much every basketball game — before Davis became a top prospect and after.

At times, Davis’ father, Anthony Sr., expressed frustration about all the losing. Hale invited him to practice so he could see how the team was coached. Davis stayed.

“They just always wanted the best for their son,” Hale says. “[They said,] ‘Whatever he wants to do, we’re going to keep him safe or keep him in the right situation. We’re going to do it.’ So that’s why they kept with Perspectives.”

After high school, Davis played one year for Kentucky. The Wildcats won a national championship, and he was chosen the Final Four’s most outstanding player. He became the first overall pick in the draft in 2012 and won a gold medal with Team USA in London that summer.

Never again was there a time in Davis’ life like those days at Perspectives.

::

Davis still practices in an unconventional space. At the Lakers’ training facility in El Segundo, anyone who enters is reminded of the team’s storied history. There’s a display of championship rings in the upstairs offices. Trophies sit on a ledge in owner Jeanie Buss’ office, looming over the practice courts. They hang banners and retired jerseys, too, including two that belong to Kobe Bryant.

Bryant was Davis’ first connection to the Lakers organization.

During his playing days, Bryant wasn’t one to extend a warm embrace to too many young players; he had his own business to handle. But there was a certain type of player he respected, and during the 2012 Olympics in London, Davis became one.

“Anthony was different just because of his curiosity about the game itself,” Bryant says.

Davis was the youngest player on that illustrious, gold-medal-winning team, and Bryant liked Davis’ fearlessness in asking questions. They ate together. They wandered around the Olympic Village together. Davis soaked up all the knowledge he could.

“I think he was there when me and Serena had a nice conversation about work ethic and competition and how she processes competitiveness and rivals and all that,” Bryant says. “Sort of comparing notes. He was just sitting there watching.”

Over the years, Davis and Bryant remained close. After Lakers games in New Orleans, they’d find a room to sit and chat for 30 or 40 minutes if they could. Bryant recalls the group usually being comprised of Davis, his parents and Antoinette, who Bryant says was the more outgoing of the twins.

Bryant says they did not speak while Davis tried to secure a trade to the Lakers in July.

“I think the injuries have derailed it from really exploding,” Bryant says of Davis’ NBA career, “but my goodness he’s been doing some phenomenal stuff. Health is really the only obstacle for him to go and have that ridiculous Hall of Fame career.”

Davis is the Lakers’ next great hope, thousands of miles from where his playing days started, at a little school that didn’t even have a gym.

LeBron James has a new star teammate with the Lakers while the Clippers have two new superstars. From Houston to Brooklyn duos dominate.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.