Column: Documentary sheds new light on killing of 11 Israelis at 1972 Munich Olympics

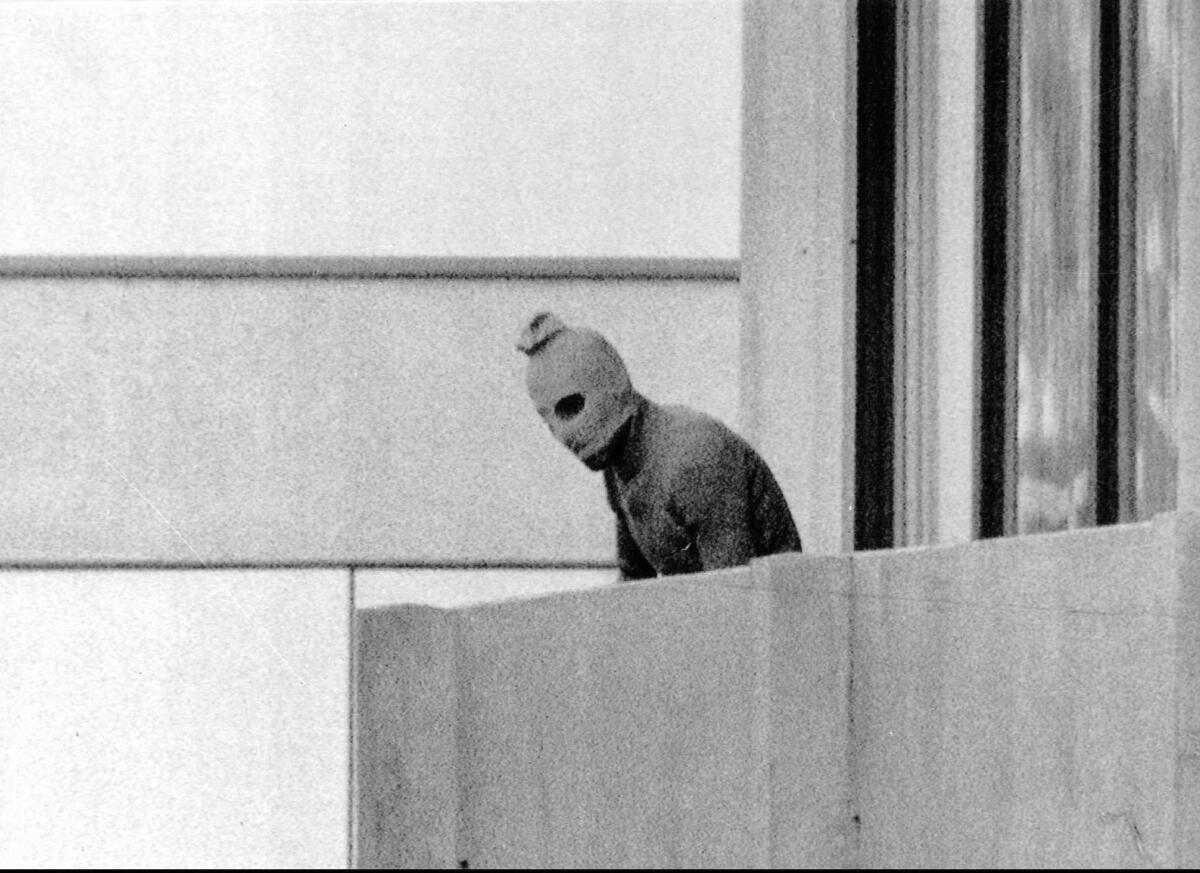

A terrorist appears on a terrace at the Olympic village in Munich in 1972, when 11 Israelis were killed.

It started with a small idea, to create a documentary about architects’ visions for expressing the intangible emotions of sorrow and respect in the form of a memorial to the 11 Israelis killed by terrorists at the 1972 Munich Olympics.

For years, the International Olympic Committee had refused to pay tribute to the victims, an egregious snub. But the ascent to the presidency of Germany’s Thomas Bach, a former fencer who had known some of the athletes, thawed relations between the IOC and the victims’ families and set the stage to build a memorial near the site of the killings.

The IOC pledged $250,000 and scheduled a tribute during the Rio de Janeiro Games to honor all Olympians who have died, including the 11 athletes and coaches killed in Munich.

It was a miracle as was the cooperation among the IOC, Bavarian and German government agencies and Israeli officials. Los Angeles attorney David Ulich and psychologist/author Dr. Steven Ungerleider, who have worked with the IOC and U.S. Olympic Committee and are on the board of the Foundation for Global Sports Development, were struck by the spirit of conciliation after Bach invited them to attend meetings involving architects and diplomats. Their idea to use architecture as a jumping-off point to tell their story soon turned into something bigger.

“We realized that we had to tell the back story a little bit as part of the film,” Ulich said, “but the bottom line is we ended up doing a short documentary from the victims’ families’ perspective.”

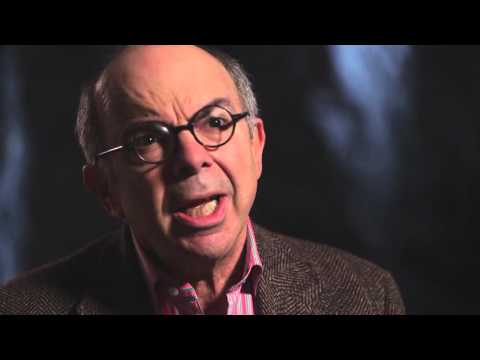

The result is “Munich ’72 and Beyond,” a 44-minute film that details the families’ persistent fight for knowledge about what happened Sept, 5, 1972, and their battle for the IOC to officially acknowledge their loved ones as members of the Olympic community. The film was co-produced by Ulich and Ungerleider and directed by documentarian Stephen Crisman. Michael Cascio was the executive producer. It was funded in part by the Los-Angeles based Foundation for Global Sports Development, which also contributed to the cost of the memorial.

The film has been screened in Brazil and at film festivals in the United States, and discussions to bring it to Los Angeles are continuing. In addition, Ungerleider said that PBS recently bought it for domestic and national distribution. Ground was broken for the memorial last November but delays have pushed back its opening until early next year.

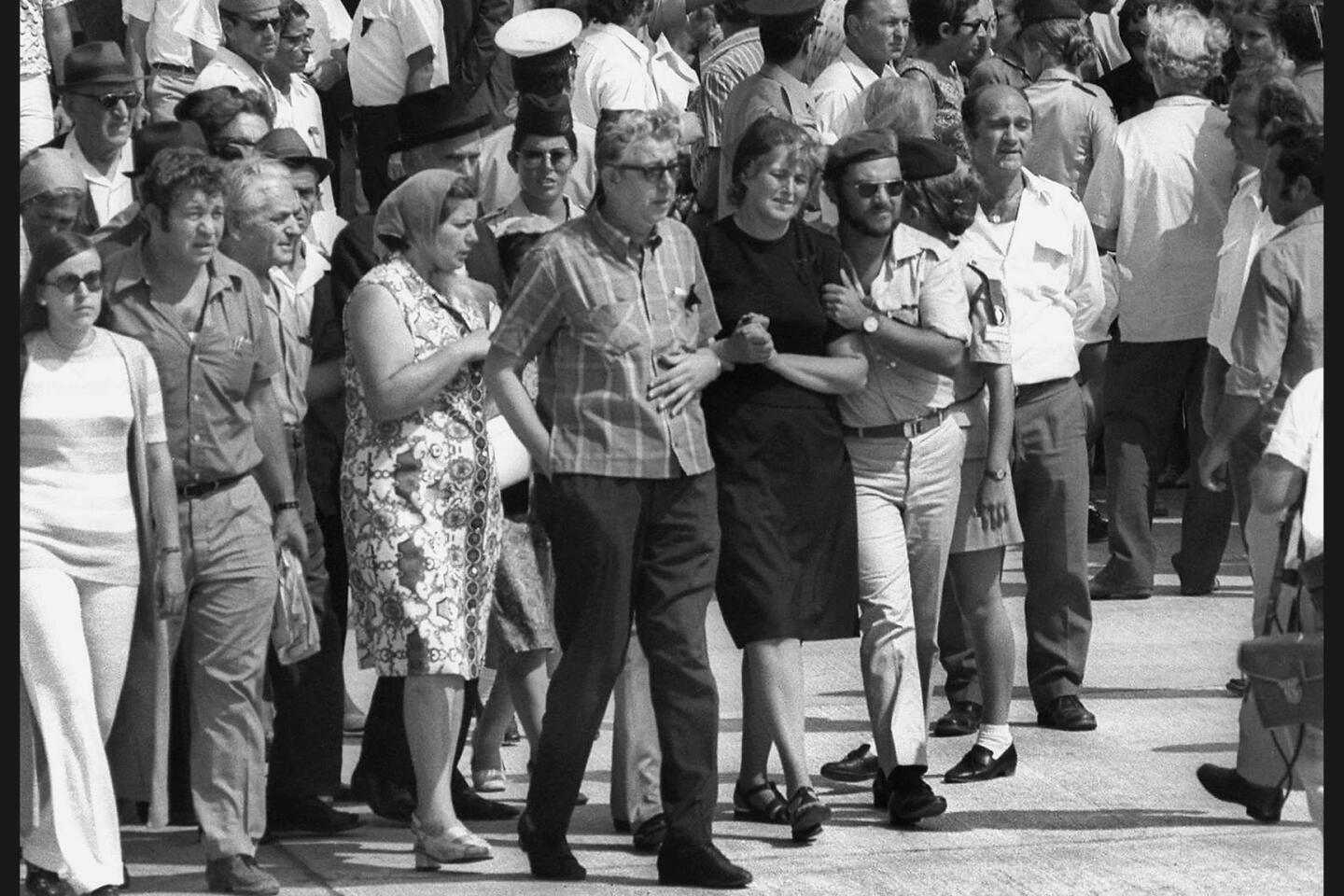

The aim of “Munich ’72 and Beyond” is to give voice to those whose pleas for recognition went ignored for decades and provide a unique perspective on the terrorism that shocked the world when it unfolded on international television 44 years ago, foreshadowing the brutality that has become a part of our fears and our world on a sadly regular basis.

“I was surprised and naïve, thinking I knew the whole story,” Ungerleider said. “I had read all the books and had seen the [Steven] Spielberg movie.”

Spielberg’s 2005 film “Munich” detailed the Israeli government’s covert retaliation against the Black September group terrorists who kidnapped and murdered the Israeli athletes and team officials.

“I thought I knew all of the gems and the skeletons and all that. Lo and behold, I didn’t.”

Among those interviewed for the documentary was 90-year-old Zvi Zamir, former chief of the Mossad, Israel’s national intelligence agency. The country’s top government officials sent Zamir to Munich as an observer hours after the massacre. “We heard some pretty amazing stories about what happened, firsthand,” Ungerleider said.

Family members discussed files shared with them by the Bavarian officials more than 20 years later but not made public. Within those files were pathology reports, information on the rescue effort that was botched by German police and photographs of the scene.

The repression of vital files was eerily familiar to Ungerleider, who gained access to archives compiled by the Stasi — East Germany’s secret police force — to write the book “Faust’s Gold,” which documented East Germany’s government-backed doping of athletes in the 1970s and ‘80s.

“It was a shocker, but it shouldn’t have been,” he said of the long-hidden Munich documents. “The German government held it close. The Mossad was sort of in on it. They knew it and they were kind of afraid to share these things because they were pretty gruesome.”

Interviews and other material that couldn’t fit into the documentary will be preserved in the memorial.

“It’s in a garden area,” Ungerleider said, “sort of a grassy knoll with beautiful trees, and 100 yards to the East is the Olympic Stadium and 100 yards to the West is the apartments where the Israelis were murdered.

“So while you’re there, observing and reading and interacting with interactive video and educational materials about the athletes, you can look either way and experience the trauma and the memory of this event.”

Follow Helene Elliott on Twitter: @helenenothelen

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.