Column: Lives will be changed during this Dodgers World Series. Here’s how mine was in 1988

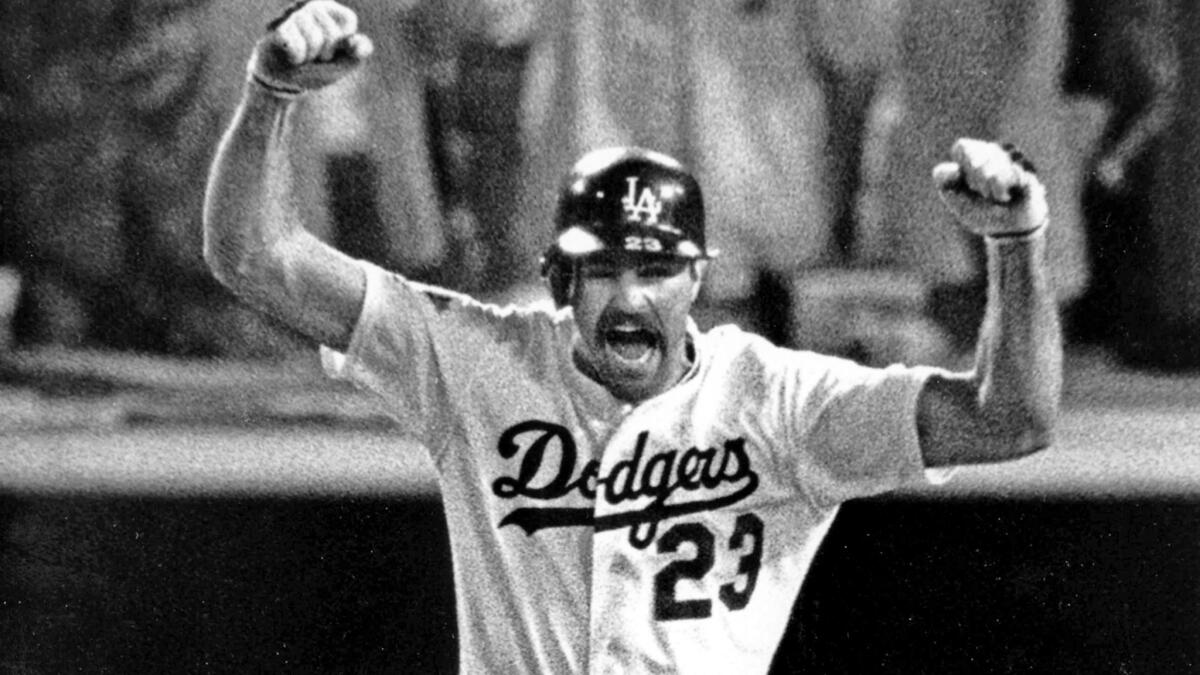

When I think about Kirk Gibson’s famous World Series home run, I don’t visualize Gibson pumping his fist or hear Vin Scully’s perfect call.

I picture my father.

The Dodgers’ long-awaited return to the World Series has resulted in a series of retrospective stories and columns, Bill Plaschke relaying a behinds-the scenes reconstruction of Gibson’s home run from Game 1 of the 1988 Series and me revisiting Orel Hershiser’s legendary season.

The legacy of that season extends beyond that, however. It was as much about the people embracing in the stands and the celebrations that erupted in households around Southern California.

Households like mine.

I spent the majority of my childhood in a small house in South Pasadena. My family moved there from Echo Park when I was 5. My father was a teacher, my mother a housewife.

The television was rarely on in our house because my Japanese mother believed too much exposure to the “dummy box” would make me and my younger brother stupid. (So much for that.) My father made exceptions for sporting events, but that was of little value to 8-year-old me. I played sports but had no interest in watching them.

I have no idea why I was in the living room while my father watched the ninth inning of Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, but I was there.

About my father: He was very laid-back. Still is. He likes to laugh and joke, but is never vulgar, never too loud. He doesn’t drink. He has an air of dignified restraint.

My perception of him changed that night — specifically the instant Gibson lauched Dennis Eckersley’s backdoor slider into the right-field pavilion.

My father picked me up and jumped up and down. He squeezed me and screamed. He was always mindful of not disturbing the neighbors, but he could not have cared less at that moment.

Who was this crazy person?

In retrospect, that night made a huge imprint on my 8-year-old mind. It wasn’t the home run itself. I didn’t understand the context of the victory or appreciate how improbable the moment was. It was my father’s reaction. I figured that if sports could move my father as much as it did, they had to be important.

Twenty-nine years later, scenes like that will play out again all over our region, and really, this is the beauty of the Dodgers’ magical run to the World Series. Not to be overly dramatic, but lives will be changed.

Hershiser said he came to a similar realization earlier this month. He has spent this October as a studio commentator on SportsNet LA’s pre- and post-game shows, but didn’t work the second games of both the National League division series and Championship Series.

“I was out in public, a restaurant, for those games,” Hershiser said. “And I got to see the impact the team has on the public.

“It’s not only the energy, it feels like you’re almost changing people’s lives, you’re changing their brain chemistry. They’re going to a happier time and a better place. It’s really amazing, the power of sports and the Dodgers.”

This was a new perspective for Hershiser.

“You realize it when you’re at the parade,” he said. “You realize it when you walk into a restaurant and people give you a standing ovation. But you’re not seeing it when you’re doing it on the field. That’s the postscript, that’s the aftermath. You’re not in the middle of it. I got to be kind of in the middle of it.”

For an entire generation of Angelenos, that kind of jubilation has existed only in the imagination. Their children known nothing about it, either. The championship drought has become multi-generational.

The Lakers provided us with moments like this, but even they are seven years removed from their last championship. Plus, as much as the Lakers won, they never reflected the city the way the Dodgers do. The city’s demographics are represented by the Dodgers’ roster, which includes players of virtually every imaginable background.

The Dodgers offer the city a reason to come together.

“When I came to Los Angeles, all I knew was that it was like 450 square miles,” Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully told me several years ago. “There was no ‘there.’ I felt like Los Angeles did not have a centerpiece.”

Dodger Stadium is now that centerpiece, that place where this diverse city gathers, 50,000-plus people at a time.

This was the unfortunate part of the team’s television deal with Spectrum. Yes, the $8-billion contract provided the Dodgers with the wherewithal to construct a roster capable of blowing away the defending World Series champion Chicago Cubs in the NLCS. But it’s the same deal that has robbed countless fathers, mothers, sons and daughters of special moments over the last four years, costing them the opportunities to spend time on the family couch watching Clayton Kershaw and Yasiel Puig, Justin Turner and Kenley Jansen.

The next five to nine days could make up for at least part of it. The city will cheer together over the results of these games — or cry, if the series unfolds as I expect and the Houston Astros win.

By the end of next week, names such as Kershaw and Turner could be spoken with the same level of reverence as Hershiser and Gibson almost three decades ago. And an 8-year-old child somewhere could forever hold a memory about his father or mother.

The Los Angeles Dodgers in the 2017 World Series

Follow Dylan Hernandez on Twitter @dylanohernandez

ALSO:

Dodgers vs. Astros: How the teams match up for the World Series

Yasiel Puig has starred in a one-man reality show during Dodgers’ postseason

Adrian Gonzalez, a clubhouse leader, chooses not to join Dodgers for this World Series

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.