Column: NHL executive Chris Snow displays remarkable resiliency despite onset of ALS

A year ago Wednesday, Kelsie and Chris Snow’s happily-ever-after took an unspeakably cruel detour.

The weakness Chris had felt in his right hand was confirmed that day to be caused by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a disease that progressively attacks the nervous system. ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, has no cure. Snow’s case was particularly vicious: He has a rare genetic mutation like the one that took the lives of his father, two uncles and a cousin. Snow, the assistant general manager of the Calgary Flames, was given six to 18 months to live.

In the hazy weeks that followed, signs of life renewing and blooming around her seemed to taunt Kelsie. Like her husband, she’s a former Los Angeles Times summer intern and sportswriter, gifted at turning thoughts into poignant words. These will pierce your heart.

“It was like every person I’d see would be a family in the mall or a person pushing a stroller. I’d see a mom pregnant. I’d see just people who had futures,” she said. “Nobody really does. Nobody gets that promise, but we had the ability to think that the future was ours to have, and that was just taken.”

Happily, an experimental drug developed for Chris’ specific gene mutation has extended the horizon of his future. He was accepted into a clinical trial soon after his diagnosis and was lucky to get the drug tofersen instead of a placebo.

“That was just like Russian roulette, which is a whole other complicated element of it,” Kelsie said.

It’s not clear yet how long the NHL training camp will be in session, leaving the start of the Stanley Cup playoffs to be determined.

He lost the use of his right hand last summer but made Angels pitcher Jim Abbott his model to learn to throw a baseball with his left hand, lean his glove against his right hand, and then put the glove on to catch the return toss from his 8-year-old son, Cohen.

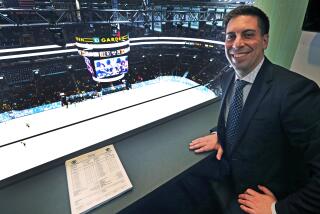

Snow, 38, spent last week holed up in his son’s bedroom — the only room in their house with a desk and a door that closes — to help the Flames prepare for the NHL draft and launch of the Stanley Cup playoffs. He can’t tie his shoes, but he can play catch and do pushups with his 5-year-old daughter Willa wriggling on his back. He is living, not waiting to die.

“I am still myself. I can walk into a room and people who don’t know, they wouldn’t know. They wouldn’t realize it,” he said. “I’m not walking slowly. I’m walking. I can run. I can skate, I can rollerblade.

“If we went back to a year ago and you painted this scene for me today I would be in tears because I would be elated. The mental challenge now is I’ve seen these benefits and I get greedy. I want it all. I want this to last for 40 more years, or more.”

Kelsie knew of Chris before they met. Formerly Kelsie Smith, she was an intern at the Times in 2004 and was impressed to hear about the previous summer’s hotshot intern, who had gotten his dream job covering hockey in Minnesota. In the summer of 2005 she was hired as an intern at the Boston Globe, where Chris had gone to cover the Red Sox even though he liked hockey better.

Most sportswriters think they know more than the people who run the teams they cover. Few get a chance to prove it. Chris did when he was hired by the Minnesota Wild a few years after then-general manager Doug Risebrough suggested he consider a front-office job. “I took a massive pay cut,” Snow said, laughing. He spent four years with the Wild and one year between jobs before he was hired by the Flames. Kelsie, who had been covering the Twins for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, moved with him when their son was 5 weeks old.

She had her own medical crisis two years ago when she suffered a stroke. She recovered, gaining an appreciation for the fragility of life. “I always say to Chris. ‘We’re not promised anything beyond today.’ Nobody is,” she said “We’re just more aware of it. It’s closer to us, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

A spokesman for the Anaheim Ducks said slightly fewer than 500 people were affected by pay cuts for employees who make $75,000 or more a year.

They’ve been as honest as possible with their children, starting last summer by explaining that Chris needed medicine to make his muscles stronger. Their son soon grasped the larger meaning.

“One day Cohen said, ‘Hey, Daddy, is what’s wrong with your hand the same thing that was wrong with Grandpa Bob?’” Kelsie said. “He figured it out on his own. We said yep, it is, but there’s a big difference. Grandpa Bob couldn’t get this medicine and at some point all illnesses were very dangerous until doctors came up with medicines for them, so we’re very lucky that Daddy can get this medicine. The doctors are very hopeful. And we can see that Daddy hasn’t gotten any worse.”

They haven’t had their son genetically tested because there’s no benefit and because Chris’ father regretted doing it. “Once you know you have the gene, you’re just waiting every day for some indicator of not feeling right,” Chris said. “If [Cohen] could be tested and then take something to preempt ever having the disease, then of course we would have him tested.”

Each time doctors told him his symptoms hadn’t worsened was a small miracle he dared to think would become a big one. But the disease encroached again in April, in a way only Kelsie recognized. While examining a photo she’d taken while the family was enjoying time together made possible by shelter-at-home requirements of the COVID-19 pandemic, she found a new droop to his brilliant smile, the smile that had drawn her to him. It was small but devastating.

“We were living in this bubble where it felt like everything was maybe just going to stay the way it was. Maybe this drug would be the magic bullet and we would just stop this where it was,” she said.

It tested Chris’ staunchly positive outlook. “The change that I’ve seen in my face, which is very likely due to a facial muscle or two that aren’t behaving the same, reintroduced some fear, some anxiety that was not there, because month after month after month, I was doing the unheard of, I was not changing,” he said.

Since then, he said, it hasn’t gotten worse, and he’s hoping he will stay at this current solid plateau for a while.

In the meantime, he’s raising funds for ALS research through #TrickShot4Snowy, challenging athletes to record themselves taking trick shots in hockey or other sports and donate to calgaryflames.com/snowystrong. It’s a new take on the Ice Bucket challenge, which raised funds for research he believes is benefiting him now. Keep him around long enough, Kelsie says, and the drug he’s taking or the next one will be the one that creates an unlimited horizon for ALS patients.

“I’ve already beaten the odds,” Chris said. “I just want to really beat them.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.