Unmasking the artist behind John Gibson’s tribute to Kobe Bryant

When the telephone rang that morning, Noah Ennis recognized the number. One of his regular customers was calling from California, probably wanting to give him some work.

It was the day after Kobe Bryant died, but Ennis didn’t make the connection. Not at first.

Though his small studio is tucked away in southeast Nebraska, hundreds of miles from the nearest NHL arena, Ennis gets calls from all around the league. Teams know about his particular talent when it comes to designing and painting the colorful masks that goalies wear.

The 32-year-old artist takes a psychological approach, asking his clients all sorts of questions, determined to transform each blank, fiberglass shell into a form of personal expression.

“Taste in music, taste in movies,” he says. “If you can pick up on those cues, you can translate what makes a goalie unique.”

Next comes the creative part, the airbrushes and paint markers, layering images across the curves, ridges and tight spaces of a canvas that can be described as unconventional if not uncooperative.

“You definitely need finesse,” he says.

The process can take a couple of weeks, leaving room for trial and error, but the call Ennis got after Bryant’s death was a rush order. The Ducks wanted a mask to commemorate the fallen Lakers star, and they wanted goalie John Gibson to have it by the weekend.

Anaheim Ducks goalie John Gibson pays tribute to Kobe Bryant and the others lost in Calabasas helicopter crash with a specially designed mask.

Hunkering down in his Shell Shock Custom Paint shop — a rented industrial space across from a liquor store in the town of Fairbury — Ennis had no way of knowing that within a few days his artwork would be worn on the ice and go viral.

In those first few hours, casting about for ideas, sketching, he merely worried about making deadline.

“It was like, what can I fit in that 50-hour window?” he recalls. “You have no room for error.”

::

Add up all the goalies on club and high school squads, college teams, minor league and NHL rosters in North America — there still isn’t enough work to support more than a small cadre of mask painters around the country.

The niche business is filled with guys who grew up drawing pictures as kids or doing graffiti as teenagers. Some studied art in college. Many happened upon their current line of work by chance.

“I was doing motorcycles, T-shirts, you name it,” says Jason Livery, who has worked for the St. Louis Blues, Michigan State and the U.S. men’s national team. “I thought I’d try goalie masks, see if it could be lucrative.”

Setting up at local rinks around St. Louis, Livery began taking orders from peewee teams. His masks got noticed by an assistant equipment manager for the Blues, who introduced him to goalie Brian Elliott.

“From there, it snowballed,” he says.

The path for Ennis was equally happenstance.

The New York native played hockey growing up but saw his career on the ice get cut short by injury at 19. His family was in the car racing business, so he took to doing bodywork for NASCAR teams.

“I started painting helmets on the side,” he recalls. “For extra cash.”

With their bright colors and corporate logos, racing helmets can be steady business — a local track might have as many drivers as a whole continent’s worth of goalies. But when Ennis, who charged between $650 and $900 for helmets, started posting photos of his work on social media, a minor league hockey coach noticed.

“We got to talking, and he asked if I could do a couple masks for his team,” Ennis recalls. “Then he started introducing me to equipment managers … they are more or less the gatekeepers for goalies.”

Over the next five years, Ennis’ clientele grew to include the Blues, Minnesota Wild and Nashville Predators. The equipment manager for that first minor league team, Matt Brayfield, got a job with the Ducks and introduced him to Gibson.

“We started with a few masks last year,” Gibson says. “Obviously, he didn’t let me down.”

At the start of each season, NHL goalies need a go-to mask and a backup, plus a few more for special occasions — outdoor games, cancer awareness, tributes to the military, etc.

Ennis and Gibson quickly developed a working relationship. The goalie would usually give the artist a few ideas, then get out of the way.

“I’ve never been the most creative guy,” Gibson says. “I put my trust in Noah … just let him run with it.”

::

The whole thing started with Brayfield. Though no one on the Ducks had a personal connection to Bryant, the assistant equipment manager thought it might be nice to pay tribute. Orange Coast College baseball coach John Altobelli and other residents were among the nine who died in that helicopter.

Gibson went along with the idea.

“Nothing too flashy,” the goalie recalls saying. “Just make it meaningful.”

When they called Ennis in Nebraska, he thought they were crazy. Mistakes are part of the process with any custom job; the Ducks weren’t leaving him any time for wiping away blunders and starting anew.

“I told them I’d do my best,” he says.

At least there was no debate over the theme. Clients, who pay Ennis anywhere from $750 to $1,500 for a mask, sometimes have ideas that don’t quite fit artistic principles such as balance or color theory. Ennis sends a rough sketch, they want changes; the back and forth can be touchy.

“Goalies are a little more free-spirited,” he says. “To stop pucks at 100 miles an hour, you have to be different.”

In this case, Ennis started by scanning the internet, searching for images associated with Bryant, jotting down 30 or so that might work on a mask. The numbers 8 and 24 were a must, as was the Black Mamba logo. The L.A. skyline seemed like a nice touch.

His concept was set by the time the mask arrived by overnight delivery. In a shop spattered with paint and hockey posters on the wall, Ennis got to work removing the cage, back plate and straps, sanding the shell and coating it with primer.

Basketball had him thinking of a streetwise vibe, something rough and gritty, but the colors presented a challenge. The Lakers wear purple and gold, just like the throwback uniforms for a certain hockey team that plays an hour north of the Ducks. Gibson had said: “I don’t want it to look like a Kings mask.”

As Ennis started to paint, working freehand, an imaginary conversation played through his head.

“What if Kobe came to me and said, ‘I want something for my man cave,’ ” he says. “What would he ask for?”

::

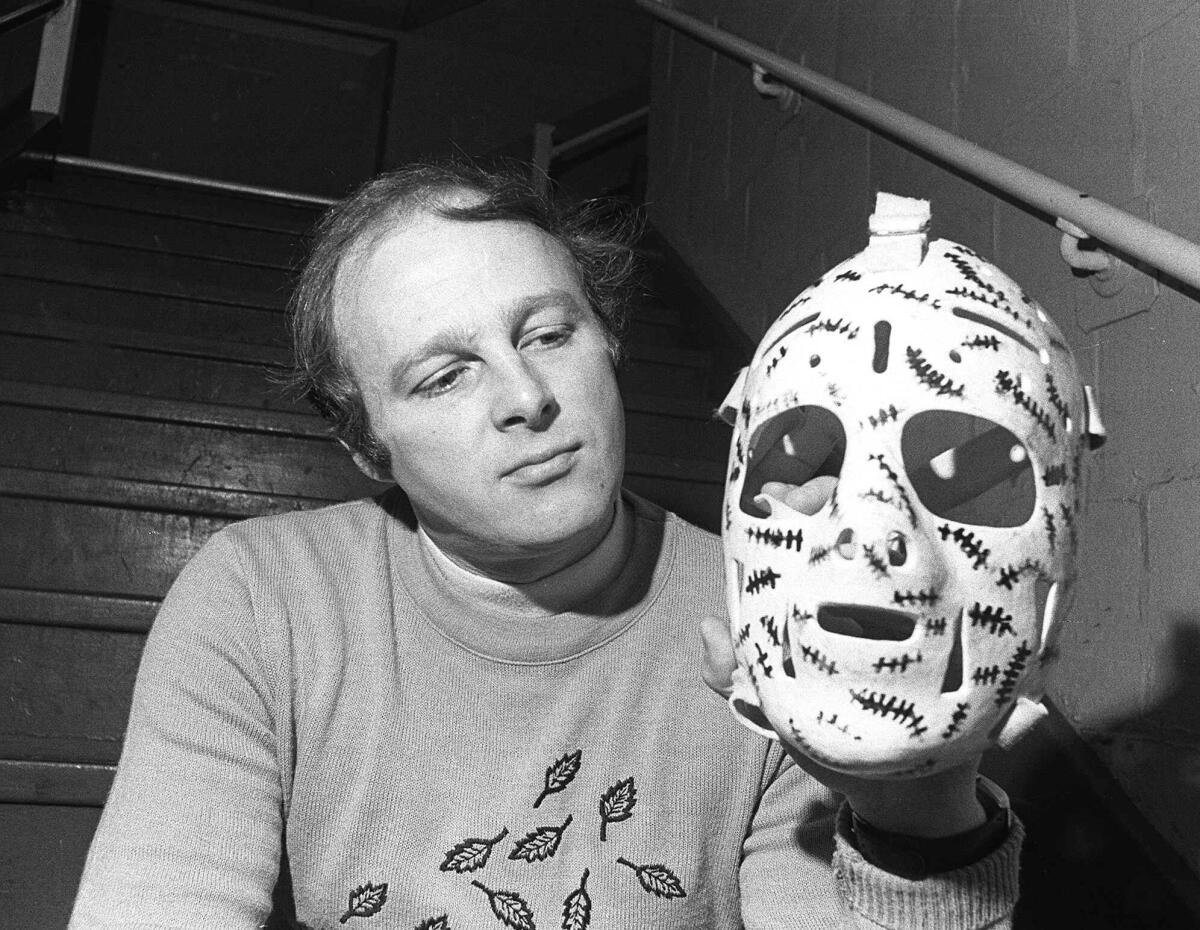

As crazy as it might seem, goalies didn’t wear masks in the early days, facing those screaming pucks bare-cheeked. A simple form of protection — thin pieces of white, contoured fiberglass — came along in the late 1950s.

Another 10 years passed before anyone thought of adding decoration.

In a story that has become hockey lore, former Boston Bruins goalie Gerry Cheevers took a shot to the head during practice in the late 1960s. The team’s trainer grabbed his mask and used a marker pen to draw stitches on the spot where Cheevers was struck.

It looked good, so they began adding more stitches. The rough doodles gave birth to an art form.

“It was pretty generic initially,” says Frank Cipra, a Canadian designer recognized among the early practitioners. “Team colors, team logo, maybe an individual thing on the back plate.”

Ken Dryden wore concentric circles in the red-and-blue colors of the Montreal Canadiens. Rogie Vachon of the Kings chose purple with a golden crown above each eye. Soon, goalies started asking for more-individualized designs.

Ed “the Eagle” Belfour had a screeching bird to match his nickname. Curtis Joseph, known as “Cujo,” favored a snarling dog from the Stephen King novel. John Vanbiesbrouck wore the logo of his Florida Panthers taken to an extreme, big and gold and gleaming.

A goalie once came to Cipra asking for naked women on his mask; the artist talked him into adding bikinis. He later agreed to paint a Mike Tyson-themed mask for Ray Emery of the Ottawa Senators, which caused a stir around the league because of the boxer’s rape conviction.

At some point, the requests became even more intricate, the designs more cluttered. Cipra worried that fans would not be able to decipher his artwork from the stands. He says: “It got too bizarre.”

About 10 years ago, he stopped taking orders from NHL teams. Looking back on more than a decade in the business, Cipra misses a time when he could paint simple scenes. He recalls a job for the Canadiens’ Jeff Hackett, who wanted a nostalgic image of kids skating on a frozen pond.

“I went home and my wife said, ‘Why don’t you paint our two boys?’ ” Cipra recalls. “That has to be my ultimate favorite.”

::

There wasn’t much time for sleep. Ennis worked through the night in his shop, grabbed a few hours’ rest and returned. He kept to this schedule for two days.

Bryant’s uniform numbers — the largest purple-and-gold elements — fit nicely on each side of the mask. The artist added five stars for each of the Lakers’ championship victories with Bryant, one star for his 81-point game, and placed a large Ducks logo on the crown.

“Obviously, I had to take a lot of things off my list,” he says. “It was a ticking time bomb, and I had to get it finished.”

Toward the end, the Ducks emailed an image they wanted, a silhouette of Bryant and daughter Gianna, which fit nicely on the back plate. Also, it occurred to Ennis that he should add the names of the other victims.

In a way, the tight deadline helped.

“I didn’t have time to second-guess myself,” he says. “Go with whatever your gut instinct tells you.”

As soon as the final coat of sealer dried, the mask was whisked back to Anaheim, arriving in time for a home game against the Tampa Bay Lightning on Friday, five days after the crash. The reaction was immediate.

“We didn’t know what to expect,” Gibson says. “It just sort of blew up.”

Television and print media ran stories nationwide. Back in Fairbury, Ennis’ cellphone would not stop buzzing with calls and texts.

“I thought it might get some traction,” he says. “Did I guess it would be trending on Twitter? Not in a million years.”

So many things might have gone wrong. He might have wavered in painting a thin line. The shell might have slipped from his hands — “Weird things happen” — smudging an image so that it had to be wiped away with thinner.

But technique and artistry are a small part of the equation. Ennis marvels at the fact that he got swept up in the saga of Bryant’s death, that he could be a part of the grieving process for fans.

“I think about all the masks I’ve done,” he says. “This one meant the most.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.