Kings’ playing surface is notoriously unruly. The ‘ice guru’ is here to fix that

It’s 3:26 p.m. on a recent Saturday and Staples Center is in the middle of a mid-day makeover.

An hour ago, the Clippers walked off the hardwood in defeat. In about 3 ½ hours, the Kings are scheduled to step on the ice for the nightcap of the arena’s basketball-hockey doubleheader.

In the meantime, dozens of Staples Center crew members are busy making the transformation happen.

Some are stacking the plush courtside seats onto carts and wheeling them away. Others are atop ladders, pulling down backboards or putting up panes of protective glass. Most are on their knees, first removing pieces of the NBA court, then peeling the massive rubber flooring that sits beneath it one dark square at a time.

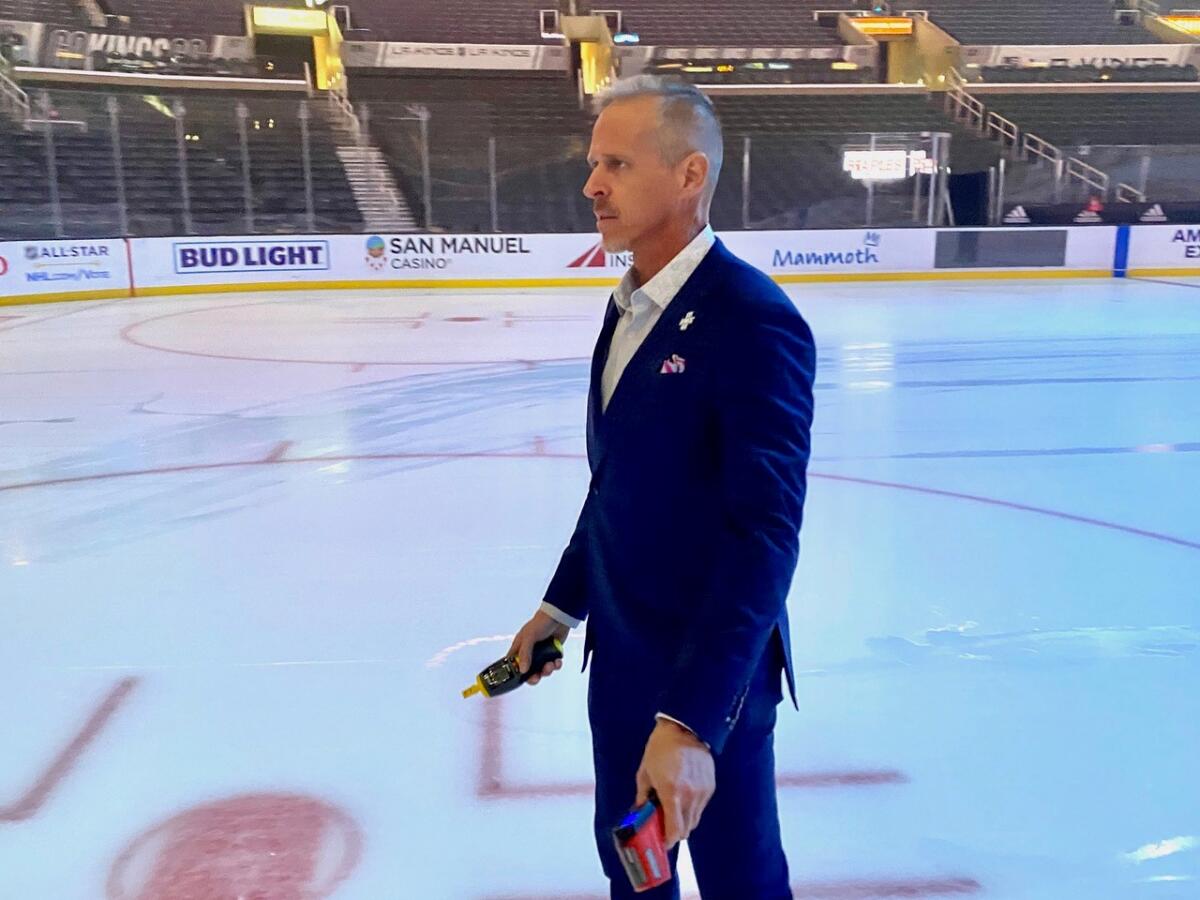

Little by little, black and brown give way to shimmering white. From the upstairs press box, Francois Martindale watches as his sheet of ice reappears.

Martindale, 58, is in his first season as the Kings’ director of ice quality and standards. A longtime caretaker of the Montreal Canadiens’ playing surface, he is now tasked with transforming Staples Center’s unruly sheet — long maligned by players as soft and slow — into what the team hopes can be one of the league’s best.

“There are so many variables here, and so many people touching different stuff,” Martindale said. “I’m just trying to take everything. Everything has to work together.”

In this role, Martindale is part scientist, part composer. He speaks of degrees and inches, surface temperatures and dew points, total dissolved solids and the effect of an ever-changing external climate. On game days, he has to get dozens of staffers and countless mechanical instruments to work in harmony.

But mostly, he considers himself something of an artist. The ice sheet is his canvas. Every game offers an opportunity for a new masterpiece.

“My aim is to make sure the players are playing on top of the sheet,” he said, explaining how factors as varied as humidity in the building and the ice crew’s shoveling formation can affect the quality of the ice, which he wants to feel hard and play fast. He wants players “on something hard, on something that doesn’t create too much snow and is fast enough to hold them on the ice, not inside of it.”

The Kings are in last place in the West after a 4-1 loss in Philadelphia, but Tyler Toffoli has played well lately and might draw trade interest.

Before he worked in hockey, Martindale did quality control work on government buildings in Quebec, Canada. But in 1994, a job posting led to an operations job with the Canadiens. Helping out the ice crew became his favorite task. He went back to school to take refrigeration and ice-making classes. Ever since, working on ice sheets has become his life’s work.

“We’re a bunch of buddies, a bunch of friends, working together and making this sheet happen,” he said.

When Kings president Luc Robitaille began searching for someone to oversee ice quality, Dan Craig, NHL Facilities Operations Manager recommended Martindale, who had been let go by the Canadiens last year (Martindale later filed a lawsuit against the Canadiens’ parent company reportedly surrounding the circumstances of his dismissal).

Having worked 25 NHL seasons and roughly 20 outdoor games on the NHL’s traveling ice-making crew in his career, Martindale came to the Kings with a fresh pair of eyes and deep wealth of knowledge.

“To have someone whose job was to strictly make the ice better was important,” Robitaille said. “I know Francois is thinking, if there’s a basketball game on Friday, ‘Man, I’ve got to make sure the ice is good for tomorrow night’s game for the Kings.’ ”

Martindale didn’t think the Kings, who have implemented new machinery such as a BluEco humidity control system in pursuit of better ice conditions, needed a total overhaul to their ice-making process.

“They were doing the right stuff, but not in the right order,” he said. “I’m enhancing what they were doing good. I’m taking away what they shouldn’t have been doing and replacing it with something else.”

The Kings and Ducks are among NHL teams working to reach a new audience. “As demographics of North America are changing, we know that we need to be relevant,” says a league official.

The building has a reputation of having soft ice, which causes pucks to bounce and skates to slice into the surface like knives through butter. As Dustin Brown put it, “The ice is garbage. It has been garbage. I don’t think it’s a problem you can fix when you have two basketball teams.”

Martindale is more optimistic. Judging by the numbers, he said, “They’ve seen ice reports like they’ve never seen here before.” But changing perceptions will take time.

On this day, he waits by the Zamboni entrance as the last pieces of rubber flooring are removed. He takes a measurement of the air (the 60.9-degree temperature is within his desired range, but the 47.1 dew point is still too high), then walks out onto the ice, slide-stepping his way to the center circle. His thermometer shows a surface temperature of 26 degrees, also too warm.

With puck drop now 90 minutes away, he knows a few tweaks will be needed. The cooling system beneath the ice needs to be turned down. More humidity needs to be removed from the air. It’s nothing he hasn’t seen before.

“With all this experience I’ve accumulated over time, you become able to read the ice just looking at it,” he said, laughing. “You don’t even need to have numbers. You just look at it and go, ‘Something is going wrong.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.