Fatherhood has helped Kings coach Todd McLellan connect better with his players

Todd and Debbie McLellan never thought they’d let so much dust settle on the cover of the book.

They originally bought “What to Expect When You’re Expecting,” after all, figuring it would serve as a de facto resource manual; that when times got tough, or when answers weren’t clear, they would turn to the wisdom within its hundreds of pages.

“A parenting bible,” Todd McLellan, 52, remembers calling it.

Then, the first-year Kings coach chuckled.

An empty-nester now, he long ago learned there is no such thing.

Parenting, McLellan found, is a lot like coaching. Experience is the only path to enlightenment. And, “until you do both,” he said, “you really don’t know what you’re into until you live it for a little while.”

It’s a fundamental truth that has shaped McLellan, the man in charge of reshaping the rebuilding Kings. Though his sons, 23-year-old Tyson and 20-year-old Cale, are out of the house, their influence on McLellan — a widely praised hire after the club finished last season in last place in the Western Conference — continues to loom large.

“Coaching prepared me to be a father,” he said. “Fatherhood has helped me adapt as we go forward into the coaching world.

“Times have changed. We have to change with them. [My sons] keep me current with those types of things.”

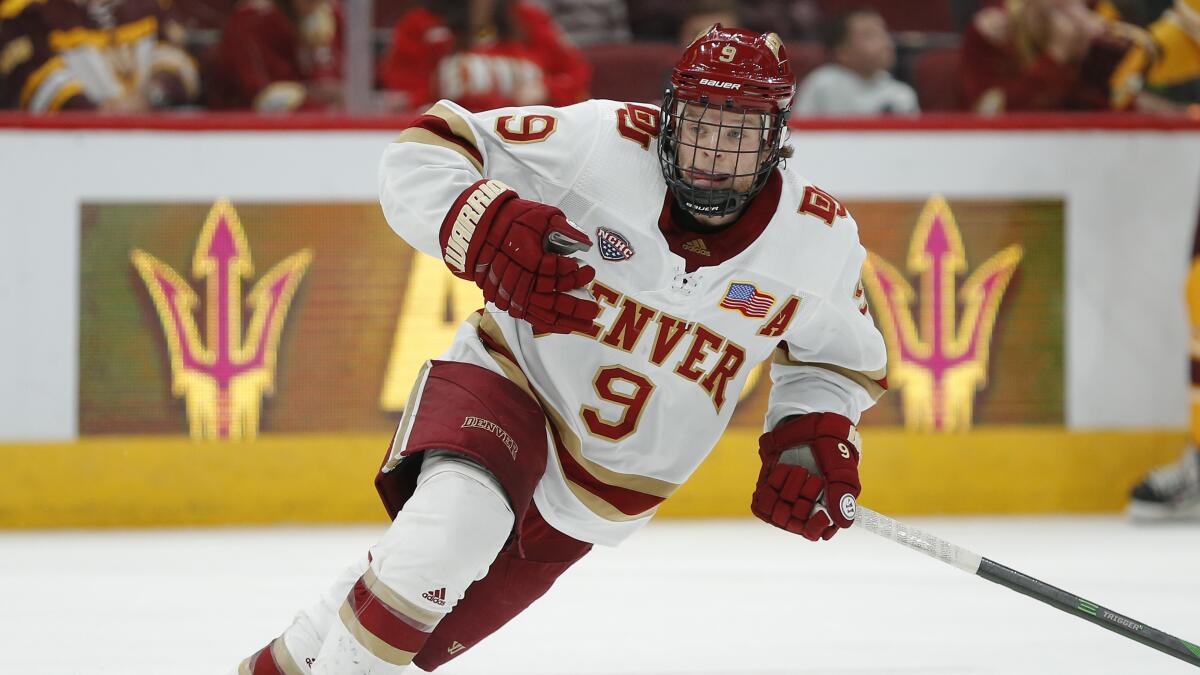

McLellan’s professional path has long been intertwined with parenthood. Tyson, now playing his senior season of college hockey at Denver University, and Cale, a student at the University of Colorado, were both born while their dad was coaching in juniors.

As the new year begins, the Kings are starting to find their stride, as evidenced by their 5-3 victory over the Flyers on Tuesday night.

The boys were school-aged by the time he reached the NHL as an assistant in Detroit in 2005. They spent most of their teenage years in San Jose, where McLellan was the head coach of the Sharks from 2008 to 2015.

When the boys were old enough, McLellan would let them tag along to work. Tyson remembers sitting in on McLellan’s coaching meetings as a kid. Cale helped out the Sharks’ equipment staff for a couple years, placing him near the end of the bench and within earshot of his dad during games.

As they learned from him, he was keenly observing them too.

In school, for instance, McLellan quickly realized his boys interacted with teachers in a way he never did.

“They have courage to reach out to a teacher and challenge a grade on a paper,” he recalled. “I would have never done that. I would have taken, ‘This is the grade I got. That’s what I earned. Away we go.’ But they’re willing to put themselves out there and say, ‘Hey, what about this? Why do you think this wasn’t like this?’ ”

At home, McLellan watched how his sons spent their spare time: how hours on a phone or computer didn’t diminish their dedication in school or sports, and how being raised in the Internet age influenced their thoughts, their motivations.

“He was always looking to see what drives us as a younger generation, what gets to us,” said Tyson, recalling how during summer trips to the family’s home in Kelowna, Canada, McLellan would play Spikeball with his sons and their friends, sit with them while they watched hockey and talked about the game, or simply razz them lounging around the house.

Said Cale: “If you ask any of my friends, they’d laugh. He’s always there. He’s always chirpin’ Tyson and I. He likes to be in that mix. He’s soaking up how we interact with each other, you know. How we live.”

McLellan learned from the hard days, such as when Tyson was suspended from school in the fourth grade along with some of his friends for teasingly tripping each other with Hula Hoops. He also cherished the rewarding ones.

Tyson left home at 16 to pursue a junior hockey career and, three years later, earned a spot on Denver’s Division I team. Cale quit the family sport at age 10 — “It took a lot of courage for him to do that,” Todd McLellan said — and began trying to develop cellphone apps as a senior in high school.

“He does a really good job of knowing when guys need a pat and some confidence, or a kick in the butt.”

— Kings forward Blake Lizotte

As they got older, McLellan started seeing his sons’ traits in some of his younger players: the inquisitive minds and insatiable need for more information, the heightened internal drives despite dwindling attention spans.

“That’s how it works in the locker room,” McLellan said. “They don’t want an hour of meeting. They don’t want 30 clips in a video session. They want to see themselves. They want to see themselves doing it right sometimes. They want to see it where they need adjustments. But they want it to the point and quick. Being around the kids, that’s where you figure that part out.”

It’s all reflected in the style with which he coaches the Kings. McLellan preaches the importance of compassion and clarity, honesty and understanding. He can be the heavy, but has found a light touch to be just as effective. And as more players of his sons’ generation trickle into the league, the more relevant those new-age nuances become.

“He does a really good job of knowing when guys need a pat and some confidence, or a kick in the butt,” said rookie forward Blake Lizotte, one of 11 players on the Kings’ roster with less than three full NHL seasons of experience. “The new up-and-coming coaches are a lot more like that, a lot more relational and are able to communicate really well instead of the old, standoff-ish, yell-when-you-make-mistakes [style].”

Even as he approaches 30 years in the coaching profession, McLellan has adopted new lines of thinking to adapt to a new generation of players.

“I understand exactly what he’s saying,” said 35-year-old forward Dustin Brown, the Kings’ longest-tenured player and a father of four. “I look at my teammates differently now. Not that they act like children, but you have a better understanding of where they’re at, what they’re thinking, how they’re thinking. You learn a lot. I’ve always said, I learn way more from my kids than they learn from me.”

Now that McLellan’s sons have finally entered adulthood, he has inherited a Kings team in the adolescence of a reboot. After seven playoff appearances and two Stanley Cup championships in a nine-year stretch between 2010-2018, the Kings have the fewest total points of any Western Conference team since the start of last season and are likely headed toward a second straight season missing the playoffs.

Unlike his past jobs with the Sharks (where he missed the playoffs once in seven years) and Edmonton Oilers (where he coached arguably the best player in the game in Connor McDavid), McLellan signed a five-year contract with the Kings understanding this job would take more time to get right.

“This team has gone through the whole process, and now we’re back to putty and we’re trying to mold it again,” he said. “It doesn’t happen as quick. You’re a little more patient.”

Once again, he goes back to his sons. When they were young, he points out, the process was more important than the results. He could live with bad grades. He could accept if they didn’t make a team. Back then, it was about building good habits, cementing a solid structure. They were building for the future — just as the Kings are now.

“That’s part of the plan, is to set standards and create expectations amongst each other in the locker room,” McLellan said, slipping on his coach’s hat. “Apply it in the game. Make mistakes. Correct them. And grow. So later on, we can take advantage of all the training we’ve had.”

After all, it worked for him as a father. Tyson is an alternate captain with a Denver team that reached the Frozen Four last year. Cale is in charge of multiple start-up companies, most notably a food-delivery app called “9-Eighteen” that is being used by several golf courses and resorts in Canada.

“I think that’s what Tyson and Cale are doing in college,” McLellan said. “Because my wife and I were there helping them through elementary and high school, and checking their papers and making sure they’re doing their homework. They’re ready now.”

McLellan thinks his Kings team is on a similarly ascendant path. Just as he couldn’t rush his sons to adulthood, he can’t skip through the transitional phase with his new team. His lessons from fatherhood have never been as relatable at the rink. His boys are grown now. He is ready to raise a hockey team of his own.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.