Montreal Canadiens hockey holds a special mystique among players, fans and the city

MONTREAL — The riot that followed the suspension of right winger Maurice Richard. The line of 50,000 people who passed the bier of Howie Morenz at center ice of the Montreal Forum after he died following a hockey injury.

The purchase of the entire Quebec Senior Hockey League to assure that the masterly young Jean Beliveau would wear the bleu, blanc et rouge of the Montreal Canadiens. The excerpt from the World War I poem “In Flanders Field” that the Canadiens will pass Saturday night as they take the ice at the Bell Centre to play the Kings.

For two-thirds of a century, a line from that verse has appeared in the locker room of Montreal’s hockey gladiators.

The poem, written by Canadian soldier and surgeon John McCrae and asserting “To you from failing hands we throw/The torch; be yours to hold it high,” is symbolic of hockey’s most storied tradition in its most garlanded franchise in its most beloved city.

The Canadiens of Max Domi, Carey Price and Nick Suzuki that Todd McLellan’s Kings will confront Saturday have fallen on hard times, even missing the playoffs the last two seasons.

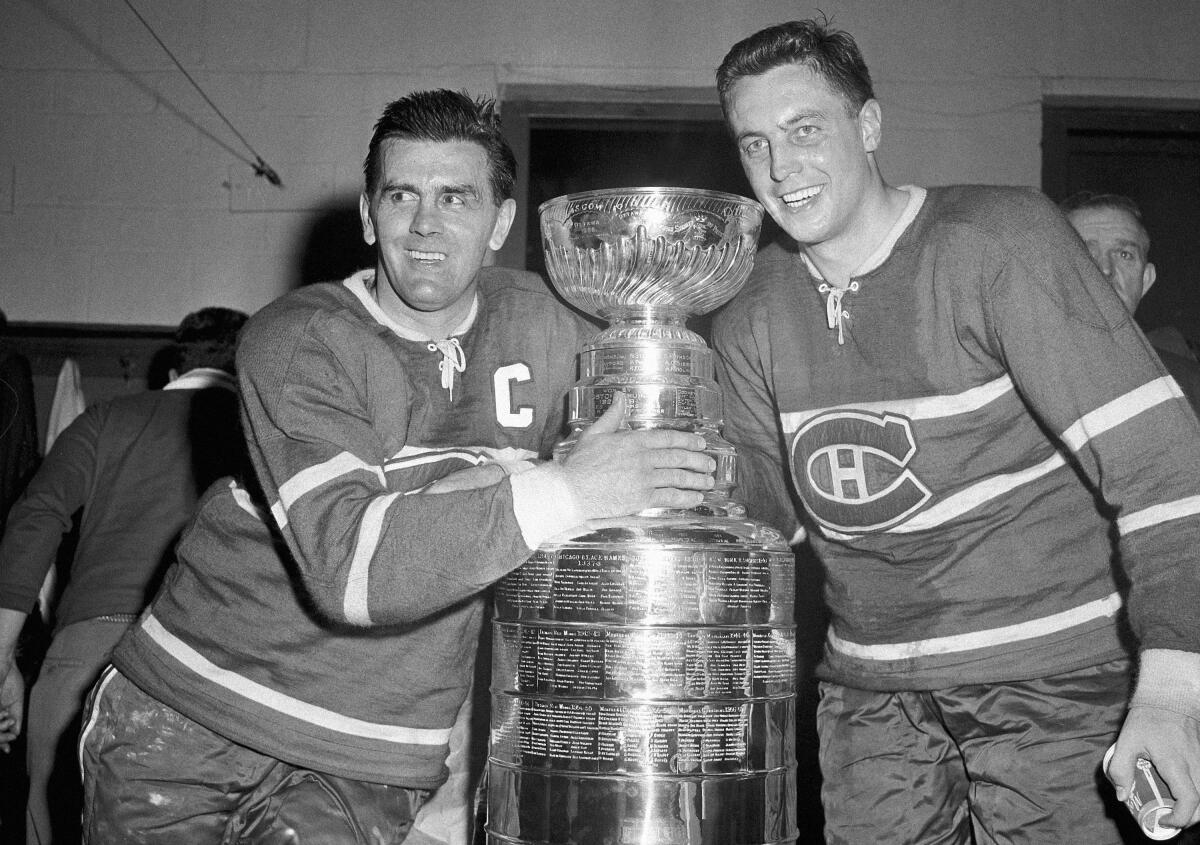

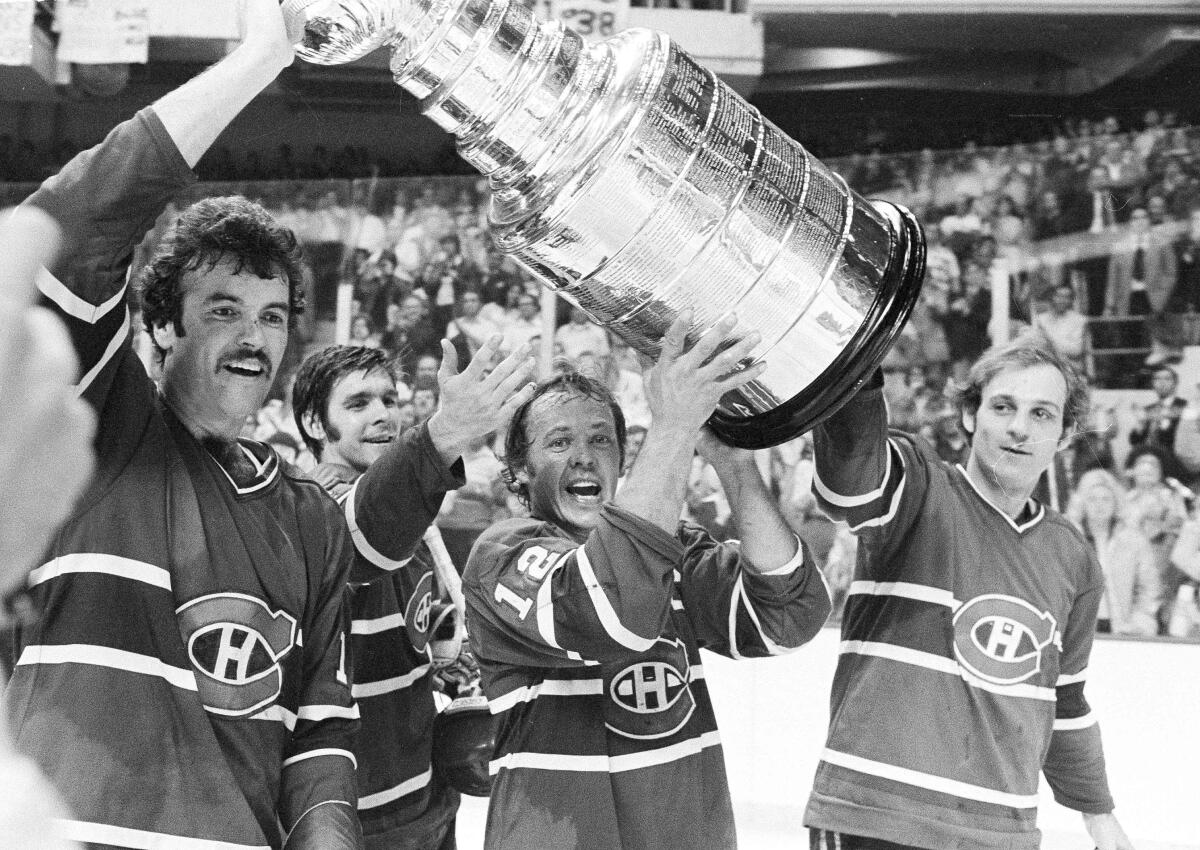

But the Habs, as they are known here — the term is short for “Habitants,” the French settlers along the St. Lawrence River in colonial times — still retain the most Stanley Cups, their 24 championships, eclipsed in major sports only by the 27 possessed by the New York Yankees, a standard no hockey team is likely to match.

“The Canadiens are a major part of character of this city, even in times like this when they are not doing that well,” says Daniel Beland, director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada. “Its players are icons in Quebec. It’s not just a franchise. It is one of the major institutions of Montreal.”

That was evident less than a month ago, when the team opened its 108th home season with heraldry worthy of a royal occasion. As former Montreal Gazette columnist Michael Farber once wrote, perhaps hyperbolically but certainly plausibly, “Only two institutions truly grasp ceremony: the House of Windsor and the Montreal Canadiens.”

Kings coach Todd McLellan and Ducks coach Dallas Eakins have cut back on morning skates, as athletes are better conditioned and more cautiously cared for.

Known in French as Les Glorieux, the Canadiens have inspired poetic elegies, scholarly monographs — and athletic awe, in contemporary time as in past years. The most potent testimony comes less from their players than from their opponents. They loved to play in Montreal, even though they seldom won in Montreal.

“It was different playing in Montreal than anywhere else,” says Ben Lovejoy, a former defenseman for four NHL teams, including the Ducks (2012-2015), who first played in Quebec in the International Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament two decades ago. “It is the most educated fan base. You go into the rink there and they are rabid — but they also appreciate good hockey.

“They will politely clap for a nice play going through the neutral zone or a nice back check or small plays. The small plays that the untrained eye may not see are clearly seen in Montreal.”

Now listen to Eddie Johnston, who played in the NHL for 22 years and was the winning goalie for the Boston Bruins’ Stanley Cup championships in 1970 and 1972. “Playing in Montreal was like playing in Yankee Stadium,” he says. “When there were only six teams in the NHL, everybody — all the great players — seemed to belong to the Canadiens. And their fans were so used to winning that they expected it. It was hard playing against them for one reason: They had the best team, always.”

The Montreal mystique did not develop only because the first organized game was at the Victoria Skating Rink on March 3, 1875, eight years after Canadian Confederation; nor because of the emergence of the game as a magnet for popular attraction is intimately related to the Canadiens; nor even because the Canadiens in all their glory were New England Patriots of hockey, only more formidable.

That mystique developed because the Canadiens are intimately linked with the French language and with French heroes. The old Montreal Forum, where the Habs played until 1996 and where the rafters were crowded with Stanley Cup banners, was where Francophones could compete and excel in a place dominated by Anglophones.

“In drama, in fiction, in television and movies, it is front and center in the culture,” says Christopher Kirkey, director of the Center for the Study of Canada and Institute on Québec Studies at the State University of New York College at Plattsburgh. “Life in many families in Quebec still revolves around hockey — practices, games, Saturday night on television. You can walk into a sports bar with 24 televisions, and 24 of them will be tuned to the Canadiens.”

Everyone is watching — everyone, that is, except those who on winter evenings are playing hockey themselves. The game is so ingrained in the city that the father of hockey icon Mario Lemieux, now one of the owners of the Pittsburgh Penguins, would cart snow indoors and onto the family home in the Ville-Émard district of Montreal and let it freeze so they could play in the living room.

“The way people in Montreal think about hockey is not the way other people think about hockey,” says Brian Kennedy, a Pasadena City College English professor who played youth hockey in Montreal and has written several books on hockey. “The mind of a Montrealer is not like the ordinary mind. Everybody in Montreal still has the hockey sweater they had as a child. I have the programs from my first games and the tickets too.”

This loyalty travels, the way Dodgers loyalty moved from Brooklyn to Chavez Ravine and the way Steelers loyalty moved to Charlotte and Houston when Pittsburgh’s steel industry collapsed and its workers sought jobs in cities in America’s South. You can see those yellow Terrible Towels in the stands at Bank of America Stadium and NRG Stadium when the Steelers play there.

“Your childhood loyalty to a team like the Canadiens is very hard to lose,” says Marc Lortie, who grew up in Quebec City as a fan of the Habs of the Béliveau years (1950-1971) and who as Canada’s ambassador to Chile and France would rise in the morning to check his favorite team’s scores. “Hockey is part of our DNA. In Quebec, hockey was the most important event that could take place on Saturday night. We were all Francophone and Catholic and Canadiens fans. That was who we were, and that’s who I am today.”

(Montreal once had two teams, the Canadiens with a French accent and the Maroons with an English accent. The Maroons — whose Hall of Fame star Hooley Smith is considered the first NHL player to wear a helmet — won the Stanley Cup in 1926 and 1935, and one of its season-ticket holders was a furrier named Bernard Marks.

During an especially torrid Canadiens-Maroons game at the Forum, he was ejected from the arena for spitting in the face of a Canadiens fan, one of many colorful stories surrounding my Montreal grandfather.)

Today, sports executives strive to build a fan experience that will create a fan base remotely like that still owned by the Canadiens. It is an elusive goal.

“You can’t replicate Montreal hockey anywhere,” says David Morehouse, president of the Pittsburgh Penguins. “You shouldn’t even try. Hockey is what made a French-Canadian city in Quebec a major international sports city not just known but revered for excellence.”

These days, however, there is excellence elsewhere as well. The sport rooted in the experience of Francophone Canada now thrives beyond Montreal, in Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver — all very important centers in Canada and in hockey.

“That’s a good thing,” says Colin Howell, who directs the Center for the Study of Sport and Health at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and is the author of “Blood, Sweat & Cheers: Sport & the Making of Modern Canada,” published in 2001. “The metropolitan dominance of the old cities is in decline, in hockey and maybe in Canada.”

That is a climate change that complements global climate change. Even so, the winters remain robust here, with average low temperatures here around 32 degrees Fahrenheit this month — plunging to average lows of about 10 degrees in January.

Nearly six decades ago, on Feb. 1,1962, the first-place Canadiens played their archrivals, the Toronto Maple Leafs, at the Forum. Nine members of the Habs were born in the same city: Montreal. The temperature outside was minus-25 degrees. The Canadiens won 5-2.

“Hockey fit with the ‘northern myth’ of Canada, a place where people overcame winter— embraced winter — by doing things like playing hockey,” says Andrew Holman, a historian at Bridgewater State University in Massachusetts and co-author of “Hockey: A Global History,” published last year. “If Canada had been anyplace else, it would not have worked. But hockey also is not British and it’s not American. It’s neither ‘Mum’ nor ‘Big Brother.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.