The tour starts at Section 1. At the top of Dodger Stadium. Where the mountainous backdrop, picturesque playing surface and 56,000 seats all come into view.

Before thousands of fans file into the ballpark every night, groups of about a dozen each walk the grounds on guided tours every afternoon.

They go from the top deck to the field-level seats. From the historic hallway that leads to the clubhouse, where World Series trophies and a century’s worth of awards adorn the walls, to the baseball diamond the Dodgers have called home for the last 60 years.

They don’t come for modern amenities. They don’t see many cutting-edge features. They aren’t dazzled by architectural advancements.

This place offers something different. A portal to the past. A connection to the present.

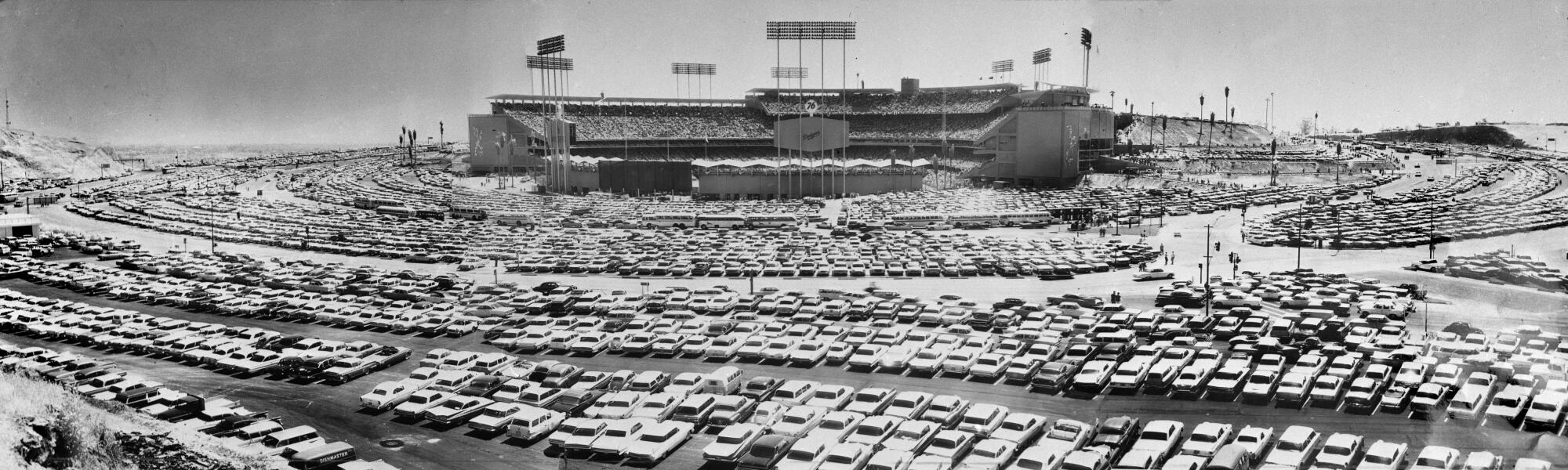

Dodger Stadium is a distinctly wonderful place to watch a baseball game, but a most difficult place to attend a baseball game.

And, even after all this time, a sporting and cultural touchstone destined to last well into the future.

“It’s kind of like baseball’s cathedral,” longtime Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner said.

Indeed, while many venues could be called one of baseball’s spiritual homes, Dodger Stadium is near the top of the list.

And next week, it will be under the sport’s biggest spotlight once again.

For the first time since 1980, Dodger Stadium will host Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game. And though such big names as Aaron Judge, Shohei Ohtani and Mike Trout might headline, it’s the 60-year-old stadium that, as much as anything else, will take center stage.

“When you get deep down to it as a player,”Dodgers pitcher Clayton Kershaw said, “I don’t think there’s anything better.”

“It’s long overdue,” Turner added. “That energy and that buzz and that atmosphere that is created here, which has a lot to do with our fan base, makes it an exciting place to play.”

It’s not just that Dodger Stadium has baseball’s largest seating capacity.

Or that it’s the majors’ third-oldest active venue, after only Wrigley Field and Fenway Park.

Or that, of MLB’s 30 current stadiums, few mimic its style, match its history or offer an equally distinct feel.

“Dodger Stadium sitting up there alone — sort of literally and figuratively — in this cavernous parkland surrounded by Chavez Ravine is just so unique and special,” said Janet Marie Smith, a longtime stadium architect who serves as the Dodgers’ executive vice president of planning and development.

“I’m sorry to keep using the word ‘unique,’” she added during a recent interview. “But it’s hard to think of a better word.”

More than a decade ago, Peter O’Malley found the sketch folded up in his father’s old files.

Now it hangs framed on a wall in his high-rise downtown L.A. office, a hand-drawn vision of Dodger Stadium that outdates the ballpark itself.

The story of Walter O’Malley’s decision to move the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles is nothing new.

A native New Yorker, Walter spent the better part of a decade trying to build a new home for the franchise in Brooklyn. When he couldn’t strike a land deal with the city, he considered relocation.

A 2020 book examines the lives forever changed by the building of Dodger Stadium, which would be brought back into focus with the rise of Fernando Valenzuela.

Officials from Los Angeles courted him to move west. Then, during a helicopter ride in 1957, Walter flew over Chavez Ravine. Dreams of a grand new stadium began dancing in his head.

Roughly two years before Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, Walter and a team of stadium architects completed the now-framed sketch, detailing everything from the layout of the concrete beams to the arrangement of each level of seating to the palm trees and plant life dotting the perimeter.

In the corner, Walter’s handwriting lists the rough capacity for each of the stadium’s four decks.

“There was never any doubt in my dad’s mind how it would look,” said Peter, who was 24 years old when the stadium opened and still vividly remembers the years-long process during which it came to fruition. “Yes, he had people helping him. Great staff. But they knew what he wanted and what he didn’t want. It was a proud moment when it opened.”

It came at a seminal point in baseball history too.

From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, new ballparks were popping up around the United States, first in such new major league markets as Milwaukee and Minnesota, then as more longtime franchises moved into new, modern venues in their home cities.

Most had similar characteristics: colossal concrete structures, often designed to accommodate a co-tenant from the NFL, and usually lacking much surrounding scenery or architectural charm.

Dodger Stadium was different. It had natural baseball sightlines in an almost perfectly symmetrical design. It was an urban park but was surrounded by a lush, hillside setting.

And while other stadiums of its era eventually went out of style, leading to a new generation of ballparks that have been built over the last quarter-century, Dodger Stadium has retained its allure.

It has ascended to iconic status.

It has become, in a city forever changing around it, an everlasting landmark too beloved to be replaced.

“This is one of the few places in baseball that’s a baseball park, where there’s no quirky things,” said Dave Roberts, who spent 2002 to 2004 with the Dodgers as a player before becoming manager ahead of the 2016 season. “The bones of this ballpark, it’s still a baseball field. And that’s something that makes this just like Wrigley or Fenway, in that conversation.”

Peter O’Malley, who inherited ownership of the Dodgers when his father died in 1979 before selling the club to News Corp. in 1997, recalled how during his ownership, suggestions to explore building a new stadium downtown or in Century City never gained traction.

“Whatever tiny interest those might have had in the beginning, it just went down and down,” he said. “[Dodger Stadium] is gonna be there a long time.”

Not even his father, he believes, could have imagined the longevity the stadium has achieved.

“I’m not sure that occurred to him,” O’Malley said. “I think what did occur to him was he saw the setting, the possibility.”

Sixty years later, Walter O’Malley’s vision lives on.

His ballpark, of course, has changed over the years.

The gas station in the center-field parking lot, part of a marketing deal that helped get the project financed, was removed long ago. New sections of field-level seating were added in what used to be foul territory. The outfield pavilions have been renovated and expanded. An entrance plaza in center field was opened last year.

But the midcentury architecture, simplistic seating design and indescribable ambiance of the place remain six decades later.

Nike and MLB unveil (and put on sale) the 2022 All-Star uniforms. The league jerseys are gone, and each player will wear a jersey with his team name.

“It’s just become more revered as time has gone on,” said Smith, who oversaw the most recent renovations, in which she was careful to accent and update the stadium’s traditional style, not overpower it with too many modern additions.

“The emotions and traditions at Dodger Stadium are just palpable,” she said. “I think it’s a testament to our club and our fan base that it’s got such a distinctive note, one that just literally vibrates throughout the park on a daily basis.”

That will be especially true Tuesday night, when the Midsummer Classic is held at Chavez Ravine for the first time since 1980, when Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Jerry Reuss, Bob Welch, Reggie Smith and Bill Russell (the Dodgers’ all-time leader for games played in the stadium) were on the National League’s team.

“It’s just an incredibly historic venue,” said Matt Gangl, the lead director for Fox Sports television coverage of the event who will be tasked with capturing the atmosphere for millions of viewers.

“You need to pay homage to the fact that there’s been a lot of history there,” he added.

It’s why the ballpark has become more relevant with time, why its significance around baseball and the Southland has, over the years, continued to grow.

It isn’t baseball’s nicest facility. It lacks the flash and luxury of newer venues around the majors.

Yet it remains sentimental to longtime spectators and leaves first-time and longtime visitors alike in awe — starting every afternoon with the tour-goers who gaze at it from above, a panoramic view with six decades worth of memories.

“The experience of Dodger Stadium and the culture of our fans I think is just electric,” Smith said, before adding with a laugh: “I’d love to think it’s all about the architecture, but I know better than that.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.