Column: Sandy Koufax statue unveiling ceremony a time of gratitude and inclusion

He rolled up the sheets of paper that sat in front of him, tight, tight, tighter still.

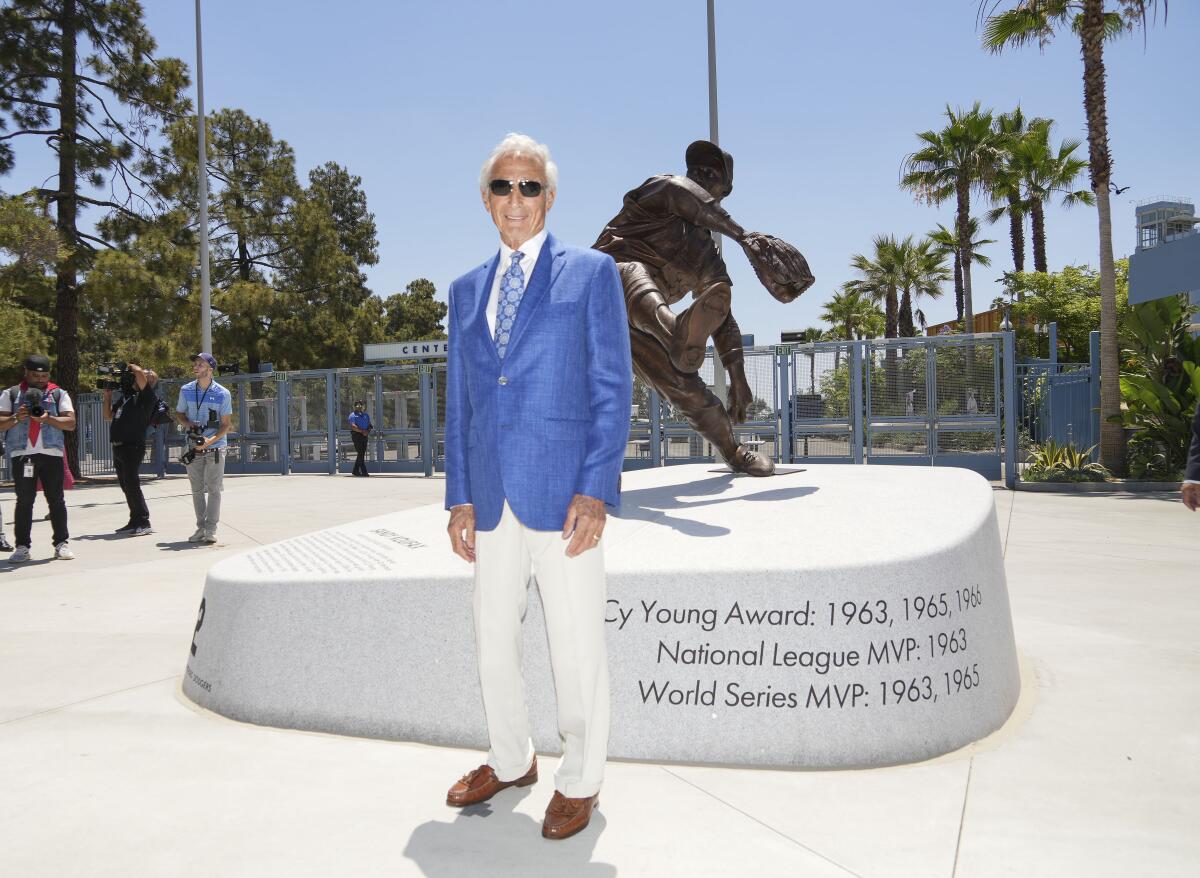

Standing behind his newly unveiled statue in the center-field plaza Saturday morning, Sandy Koufax was winding up to grace Dodger Stadium with one last pitch.

It was, appropriately, a breathtaking curveball.

It was, stunningly, a 10-minute speech from a man who hasn’t publicly spoken that much in 50 years.

It was, wondrously, the humanizing of Los Angeles’ phantom legend, a rare public pulse from a pitcher whose greatness has mostly existed in Dodgers mythology.

It turns out, at age 86, he just wanted to say thank you.

“Conventional wisdom has always said don’t give an old man a microphone, he’s got too many years to talk about,” said Koufax, looking forever young with fashionable sunglasses and a full head of white hair. “Well, I tried not to, but I’m going to start way back at the beginning … ”

And he was off, spending the entirety of his speech tracing his career from high school outfielder to Hall of Famer, expressing gratitude for figures both great and obscure, from Jackie Robinson and Don Newcombe to sandlot coach Milton Laurie and clubhouse manager Nobe Kawano.

“The list of people is incredibly long, but I’m going to go through some as quickly as I can,” he said, and so he did, from his first pitching coach, Joe Becker, to all four of his roommates, citing each by name, Doug Camilli, Carl Furillo, Norm Sherry and Dick Tracewski.

He thanked his catchers. He thanked his trainers. He thanked his relievers. He thanked his outfielders. He thanked his infielders. He thanked two different Dodgers’ ownership groups. He thanked the fans.

“Most of all I thank my teammates, all of them,” he said, before listing nearly all of them.

In all, he thanked 46 people during the span of 10 minutes, surely a record for inclusion and gratitude.

He spent the entire speech talking about others, which said everything about him. This was the real roots of his reclusive legacy. Koufax was never about Koufax. He never wanted to speak about himself because he always believed his greatness was about those who he believed carried him there.

More women are playing baseball at higher levels than ever before, but they still face challenges earning Major League Baseball roster spots.

This was the Koufax few have ever seen. This was the Koufax who nearly brought an emotional Clayton Kershaw to tears during a brief Saturday speech about his mentor and friend.

“In the years and generations to come, I hope a kid sees this statue and asks his mom or dad about Sandy Koufax, and I hope they tell him he was a great pitcher, but more than that he was a great man who represented the Dodgers with humility, kindness, and passion and class,” said Kershaw.

This humility, kindness, passion and class were indeed the highlight of a sentimental ceremony that will forever pair Koufax with Robinson, the bronze winding-up Koufax within a few steps of the bronze sliding Robinson at Dodger Stadium’s new front door.

“Sixty-seven years ago, Jackie Robinson became my teammate and friend,” Koufax said. “At that time, sharing this space with him would have been absolutely unimaginable. And today it still is. It’s one of the great honors of my life.”

The speech, which occurred in front of a small group of family and friends before Koufax was later honored during the Dodgers game with the Cleveland Guardians, also marked the happy ending of a roller-coaster relationship between Koufax and the Dodgers since he built their connection with the city during their early days in Los Angeles.

Beginning fittingly with the opening of Dodger Stadium in 1962, Koufax had the greatest five-year stretch of any pitcher in history, winning five ERA titles in a row, three Cy Young Awards, two World Series championships and an MVP. His most impactful headlines were actually made on a day he didn’t work, as he refused to pitch in the opener of the 1965 World Series because it was the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. He finished the series by shutting out the Minnesota Twins twice in four days to give the Dodgers the championship.

After he retired in 1966 at age 30 because of an arthritic elbow, the quietest of stars became sort of a ghost around Chavez Ravine, showing up unannounced, leaving without comment, always on the fringes but never in the mix.

As the years passed, with scant video evidence or recorded interviews of his greatness, he became almost like a fable, invisible everywhere but in the record books or box seats on the occasional opening day.

He began quietly working as a minor-league pitching instructor out of his Vero Beach, Fla., home in 1979, but quit suddenly in 1990 over apparent dissatisfaction with a struggling Dodgers’ farm system.

At the time, in a rare interview, he told me, “Nothing against the job, I just didn’t want it anymore.”

For the next decade he rarely associated himself with them in public, formally cutting all ties in 2003 when he was unhappy with how he was portrayed in a New York Post story that printed rumors of his personal life. The Post and the Dodgers were both owned by Rupert Murdoch.

A year later, new owner Frank McCourt brought him back, but Koufax remained on the fringes, even appearing in other team’s training camps, until Guggenheim and co-owner Stan Kasten officially brought him home within days of purchasing the team in 2012. The following spring, Koufax wore a Dodgers uniform for the first time in more than 20 years.

“There’s nothing more than the obvious,” said Kasten on Saturday when asked his reason in bringing Koufax back as an instructor. “He’s Sandy Koufax. That’s the quote. He’s Sandy Koufax.”

When Koufax showed up at spring training in 2013, it was clear that during all these years, his love for his only team had never abated.

“They’ve done a lot with the team, I understand they’ve done a lot with the stadium, and it’s the only organization I’ve ever played in or been in,” Koufax said at the time. “I came here with Jackie and Gil and Duke … and played with great people like Don and Tommy and Willie and Maury. … It feels good.”

Koufax noted in that 2013 interview that in all of his years visiting various spring training sites, he never wore another jersey.

“I wouldn’t do this anyplace else,” Koufax said. “Anyplace else they said I was working with pitchers, I went to see friends, I wasn’t working with pitchers. People would ask, could you do this [wear another jersey] … I said, I can’t.”

He will now wear that jersey forever in a sculpture that will have him pitching into Dodgers eternity.

He wants everyone to know that he will not be pitching alone.

“I think my only regret today is that so many are no longer with us and I’m unable to let them know how much I thank them and appreciated them,” he said.

The phantom legend then disappeared again, departing the Dodger Stadium center-field plaza stage with a voice as thick as his undying grip on an eternally awestruck city and its baseball team.

“I love you one and all,” Sandy Koufax said. “I’m done.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.