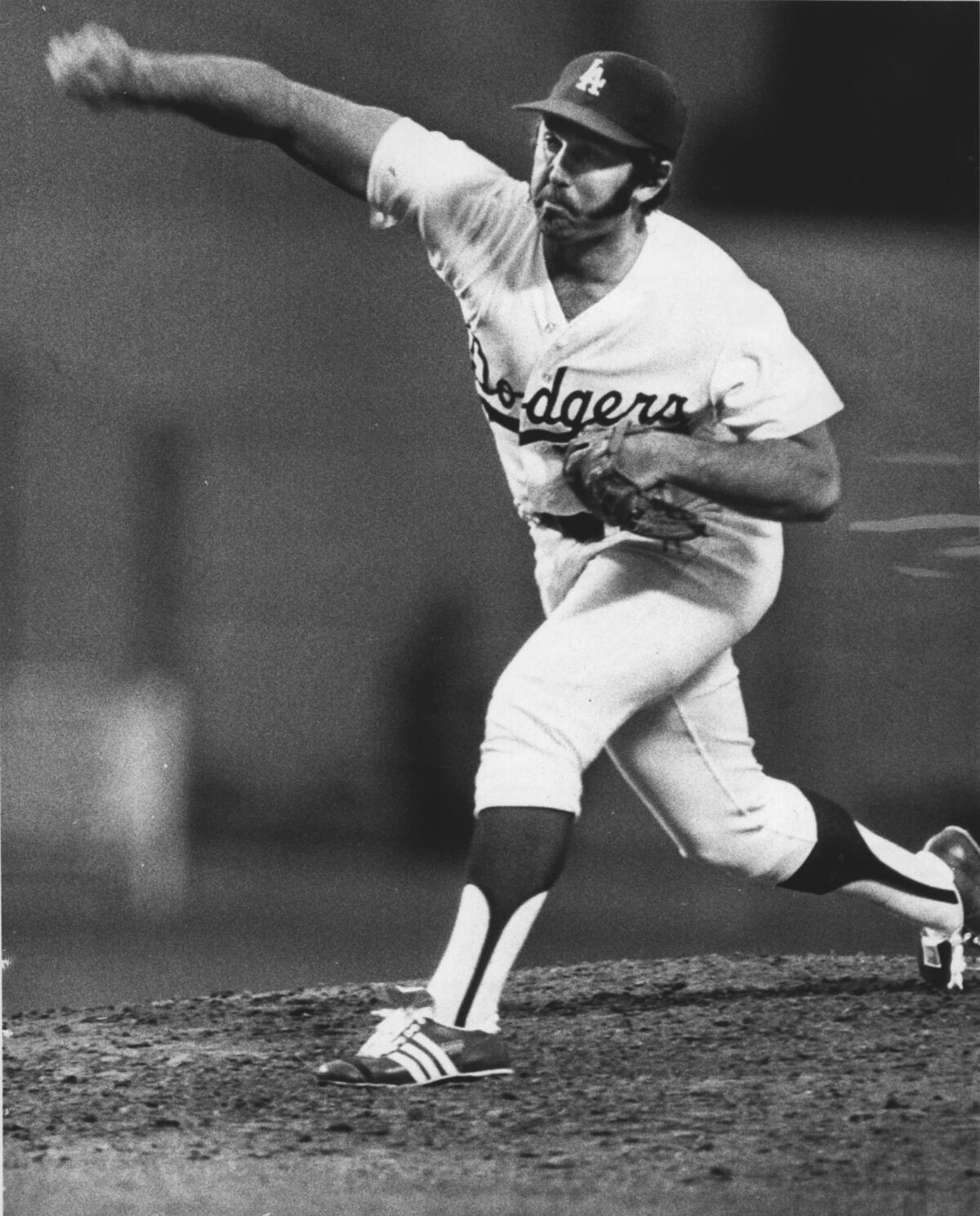

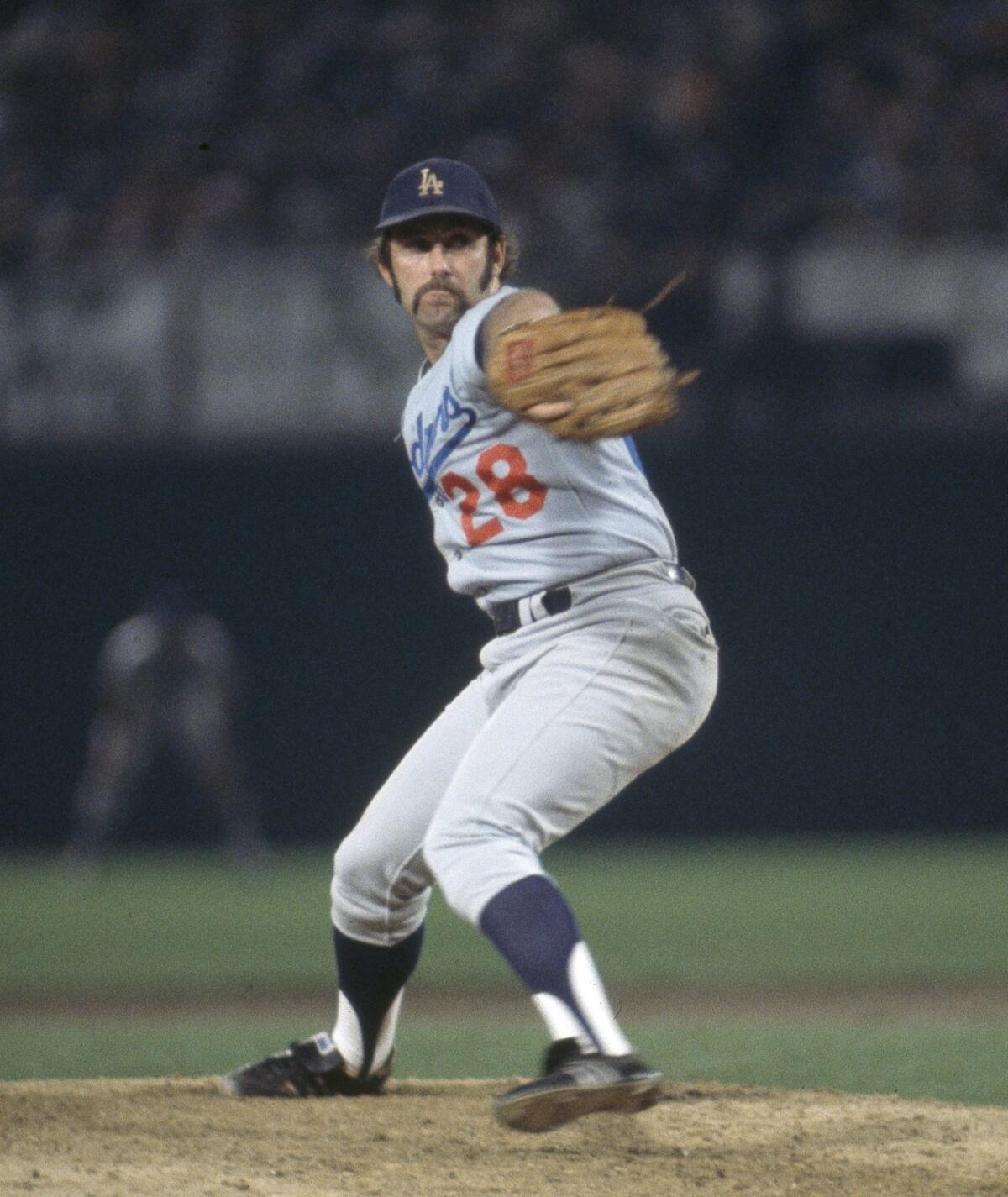

Former Dodgers star reliever Mike Marshall dies at 78

Mike Marshall, who set a major league standard for endurance during an iconoclastic but award-winning career, died Tuesday, the team said. He was 78.

The Dodgers said he died in Zephyrhills, Fla., where he resided. The team did not announce a cause of death.

In 1974, as the Dodgers’ top relief pitcher, he appeared in 106 games, still the major league record. He pitched in all five games of the World Series that year, including a memorable pickoff of Herb Washington, the track star the Oakland Athletics signed for the sole purpose of pinch-running.

Marshall won the National League Cy Young Award as the league’s best pitcher that year, the first relief pitcher to win the award. He ranked among the top five in Cy Young voting four times, unusually high finishes for a relief pitcher. Then again, Marshall finished an unusually high number of games, with an unusually high number of innings.

He pitched in 13 consecutive games in 1974, pitching the final four innings one day and the final inning the next. He pitched 208 1/3 innings and faced 857 batters that year, one of three in which he appeared in at least 90 games.

Only five men in major league history have appeared in 90 games, even once. The most recent pitcher to appear in at least 90 games, Pedro Feliciano in 2010, pitched 62 2/3 innings and faced 280 batters.

Pitcher Trevor Bauer said he will do a deep dive into advanced statistics and video to determine the reasons for the high percentage of long balls.

Marshall attributed his endurance to a self-taught regimen he adopted in 1967, after his rookie season left his pitching arm so sore he could not lift his arm high enough to shave. He ordered X-rays, studied high-speed film and determined that he was throwing the ball all wrong. He could minimize stress on the arm, he concluded, if he delivered the ball by turning his hand so that his wrist rotated into his body and his thumb pointed down, not up. He streamlined his body’s motion during his delivery.

In retrospect, Marshall was a man ahead of his time.

The Dodgers’ Trevor Bauer, for instance, worked independently and with private coaches to refine his game and win the NL Cy Young Award last year. Bauer and many other pitchers make use of sophisticated biomechanical feedback that shows stress points in the delivery, a technology-driven improvement toward the same goals Marshall had half a century ago, on the way to his doctorate degree in kinesiology.

Today, teams embrace technology-driven instruction, even from outside the organization, and freely hire coaches who never played professional baseball. In Marshall’s day, players were expected to follow standardized instruction and obey coaches, not challenge them.

“I’m afraid Mike’s problem is that he’s too intelligent and has too much education,” pitcher Jim Bouton wrote in “Ball Four,” published in 1970.

Marshall pitched 14 seasons in the major leagues, but for nine teams, never spending as many as four full seasons with the same team. He believed teams dumped him in part because of his activism in the nascent players’ union.

After he retired in 1981, he thought teams would approach him about coaching. He believed, after all, that he could teach techniques that could virtually eliminate the chance of a pitcher suffering an arm injury.

“Without listening to what I have to say, ‘traditional’ baseball pitching coaches, orthopedic surgeons, biomechanists, general managers and almost everybody else that coaches baseball believe that all baseball pitchers will eventually suffer injuries,” Marshall wrote on his website.

He did not hide his disdain for conventional wisdom, or its purveyors that declined to turn their team’s pitchers over to him.

“They’re still teaching the same motion of the first guy who won a ballgame,” Marshall told the Kansas City Star in 2007. “There’s not one of them who knows anything of science. They think Sir Isaac Newton invented the Fig Newton.”

Without a professional outlet for his coaching, Marshall opened a pitching school in Florida, but the pupils generally had washed out of the major leagues or had little hope of getting there. In 2007, Times staff writer Kevin Baxter visited the school, where Marshall had introduced work with weights and weighted balls long before such work became accepted in the major leagues.

Chris Taylor lashes a 97-mph fastball into right-center field for a three-run double in the sixth inning of the Dodgers’ 9-4 win over the St. Louis Cardinals.

“They just didn’t want my ideas to get in,” Marshall told The Times. “That’s ridiculous. But that’s the small-mindedness of Major League Baseball. They don’t know what the hell they’re doing. And if I get in, everybody will know that they don’t know what the hell they’re doing.”

In his interview with the Star, Marshall expressed his frustration that even former teammates and colleagues within the major leagues would not return his calls. He talked about a movie that hit home for him.

“You spend your lifetime working on something that everybody ignores,” he said, “and then you’ll understand.”

Marshall is survived by his wife, Erica, and three daughters: Rebekah, Deborah and Kerry Jo.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.