Easy now, San Diego. The Giants still loom large as the Dodgers’ primary rival

Back when San Diego had an NFL team, that team had a catchy jingle: “San Diego Super Chargers!” Based upon the hype of the past few months, it was almost if the town’s baseball team had changed its name to the San Diego Super Padres.

Blake Snell here, Yu Darvish there, Fernando Tatis Jr. everywhere. The Padres are trendy, exciting, and bloody good. They have staked their claim as the Dodgers’ primary rival in the National League West.

“That’s cute,” sniffed an employee of the San Francisco Giants.

Yes, the Padres ought to challenge the Dodgers’ ownership of the division. Yes, the Padres and Dodgers might be the two best teams in baseball.

The Padres agreed with shortstop Fernando Tatis Jr. on the longest contract ever, further cementing the Dodgers-Padres rivalry as the best in baseball.

But the Padres and their fans cannot just declare an enduring rivalry based on winning the winter. The Padres had a nice season last year. The Dodgers swept them out of the playoffs and won the World Series, something the Padres never have done.

The Dodgers and Giants transcend sports. In 1962 — seven years before the Padres were born — popular entertainer Danny Kaye recorded a charming song about the already storied rivalry between the Dodgers and Giants, name-dropping Sandy Koufax and Willie Mays, chronicling a fictional game between the “Bums” and the “Jints,” and playfully inventing the “Miller-Hiller-Haller Hallelujah Twist.”

In 2018, when Dianne Feinstein ran for re-election, her campaign staged a fundraiser in Los Angeles, with the cheeky theme that the teams did not agree on anything except Feinstein for Senate.

The Dodgers and Giants sent decorations and delegations, and the banter was all in good fun. Of course, the Giants had won the World Series three times that decade, and Feinstein is a former mayor of San Francisco. At one point, she was standing next to Giants President Larry Baer.

“She took the World Series ring off my finger,” Baer said, “and stuck it in Ron Cey’s face and said, ‘When are you going to get one of these?’ ”

After a four-month delay because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Dodgers open the season with an 8-1 victory over the Giants at Dodger Stadium.

The Giants are not about to surrender their identity as the Dodgers’ chief antagonist.

The rivalry has endured since the 19th century, when the Dodgers represented the New York City borough of Brooklyn against the Giants, from mighty Manhattan. The two teams moved to California in tandem, in 1958. There was a time when San Francisco was the mightiest city in California, but that time has long passed.

“L.A. blossomed into one of the great metropolises in the country,” Giants broadcaster Jon Miller said. “The Giants fans might have been a little jealous of all the attention L.A. was getting. So I think there were other things besides teams being in a pennant race.

“But I still think the root of a great rivalry has to do with battling each other in a pennant race.”

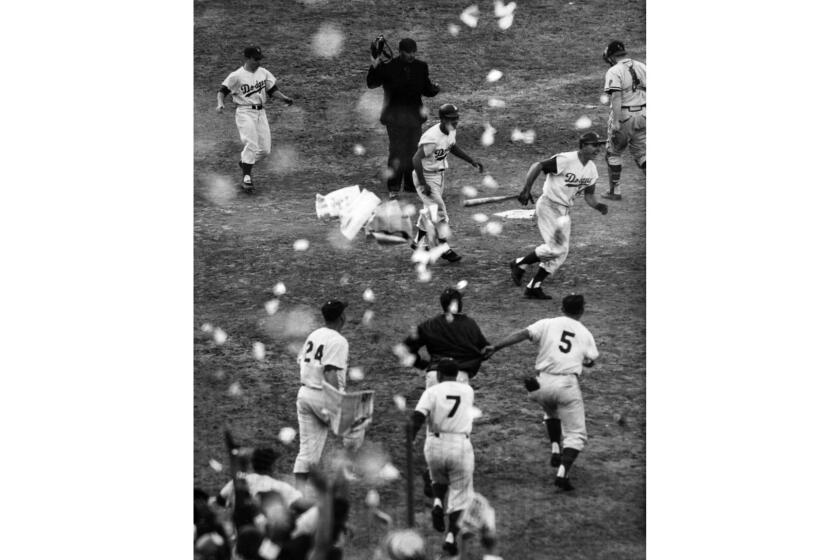

Larry Sharkey’s photo appeared on the Sep. 30, 1959, Los Angeles Times Sports section front page.

The Dodgers and Padres have finished in the top two places in standings three times — and, each time, both teams made the playoffs, killing the suspense. The Dodgers and Giants have finished in the top two places 12 times since moving to California, including seven times in this century alone.

“It’s about beating each other,” Baer said, “but the rivalry extends to knocking each other out.”

In 1951, with Mays on deck, Bobby Thomson hit “The Shot Heard ‘Round The World,” the home run that eliminated the Dodgers and sent the Giants to the World Series. In 1962, Mays scored the winning run in the sudden-death playoff that eliminated the Dodgers and sent the Giants to the World Series.

In 1982, Joe Morgan hit the home run that knocked the Dodgers out of the playoffs. In 1993, with Mays and Thomson seated in his box at Dodger Stadium, Baer watched helplessly as the fourth-place Dodgers knocked the Giants out of the playoffs.

The Padres failed to finish higher than fourth place until 1984. By then, two generations of Southern California and Bay Area fans had invested in the legendary rivalry. In Los Angeles, the only Dodgers road series televised were the ones from San Francisco. In the Bay Area, Miller was among the Giants fans who grew up listening to the Dodgers, live from L.A. on KFI.

“At night, KFI would come into the Bay Area like a local station,” Miller said. “And, come September, when the two teams were in a pennant race — and they were in a pennant race a lot when I was a kid, in the sixties — the Giants would play mostly day games.

“So we would know how their game turned out, and then the Dodgers would play that night in L.A., and I would listen to Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett.”

This season, broadcasters will call games they see only on TV. Vin Scully and Ronald Reagan called games they could not see at all.

Speedy Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills so tormented the Giants that they watered down the basepaths to slow him down.

Koufax, Hall of Famer, pitched to Mays, Hall of Famer. Don Drysdale, Hall of Famer, pitched to Willie McCovey, Hall of Famer.

Snell might pitch to Mookie Betts this season, and maybe his new employers let him complete the sixth inning.

Madison Bumgarner told Yasiel Puig not to look at him. Max Muncy told Bumgarner to go get it out of the ocean. Baer, the Giants’ president, still remembers where he was when Juan Marichal clobbered John Roseboro atop the head with a bat, in 1965.

“Driving with my parents,” Baer said, “on Highway 101.”

Fans need not remember where they were when the Padres’ Carlos Quentin charged Dodgers pitcher Zack Greinke and broke his collarbone in 2013, a forgettable footnote in the careers of itinerant ballplayers. Greinke is on his sixth team. The Padres finished 16 games behind the Dodgers that year anyway.

After Dodgers, Padres brawl in sixth, Zack Greinke leaves game

Before Ned Colletti’s nine seasons as the Dodgers’ general manager, he spent 11 seasons in the Giants’ front office. He arrived in 1995, for the final years of decrepit Candlestick Park. He asked someone why the Giants could draw 50,000 fans for the Dodgers and 15,000 fans for just about every other opponent.

“A lot of people here hate baseball,” Colletti said he was told. “They hate the Dodgers more than they hate baseball.”

In 1999, before the final night game at Candlestick, Tommy Lasorda bathed in the boos. He had retired as Dodgers manager three years earlier, but the last word would be his. He egged on the crowd, then grabbed the microphone.

“You hate yourselves,” Lasorda said, “because you love me.”

The rivalry is as much a part of California summers as the beach, but it nearly evaporated in 1992. Giants owner Bob Lurie had agreed to sell, in a deal in which the team would be moved to St. Petersburg, Fla. The league instead brokered a sale to Bay Area buyers, but only after a campaign to keep the team in San Francisco.

The person who put the most pressure on the league, according to Baer? Peter O’Malley, then the Dodgers’ owner.

“It’s a rivalry, but there’s a lot of love there,” Baer said. “We wouldn’t be the same without them, and I don’t think they’d be the same without us.”

Former Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley says he knew Tommy Lasorda “was the obvious choice” to be Walter Alston’s heir to the Dodgers’ managerial role.

The chant is the same in San Diego as it is in San Francisco: Beat L.A.!

In San Diego, traditionally, Dodgers fans drown out the cheer. In San Francisco, Giants fans would not dare let that happen.

Padres’ fans are primed for a big year, same as their team. There might come a time when Tatis Jr. is as integral to a history of the Dodgers as Mays was, but that time is not yet here.

“I think they’re going to be good for awhile, so I would not write them off as a one-year wonder by any stretch,” said Farhan Zaidi, the Giants’ president of baseball operations. “If they have that sustained run of being competitive like they’re set up to, that’s how rivalries form.”

If Zaidi can rebuild the Giants into a contender, the rest of the decade could be fun for California.

“We might get to the point where somebody has a Beat The Whole State chant,” he said. “Maybe we can have some common ground.”

The new Dodgers owners said in 2012 they’d rebuild quickly, replenish the farm system, build a sustainable winner, and invest in the right player. They are 4 for 4.

The Dodgers and Giants have not always been good at the same time. For instance, from 1972-78, the Dodgers and the Cincinnati Reds occupied the top two spots in the NL West every year.

“You’ll have teams that are good from year to year, but they’re interlopers in the rivalry between the Giants and the Dodgers,” Baer said. “There’s too much history there.”

Said Colletti: “I think it will always come back to the Giants. And, for the Giants, I think it will always come back to the Dodgers.”

It will. And, on April 9, we hope Feinstein’s staff puts the Dodgers on the office television, so the senator can see their players get one of those World Series rings.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.