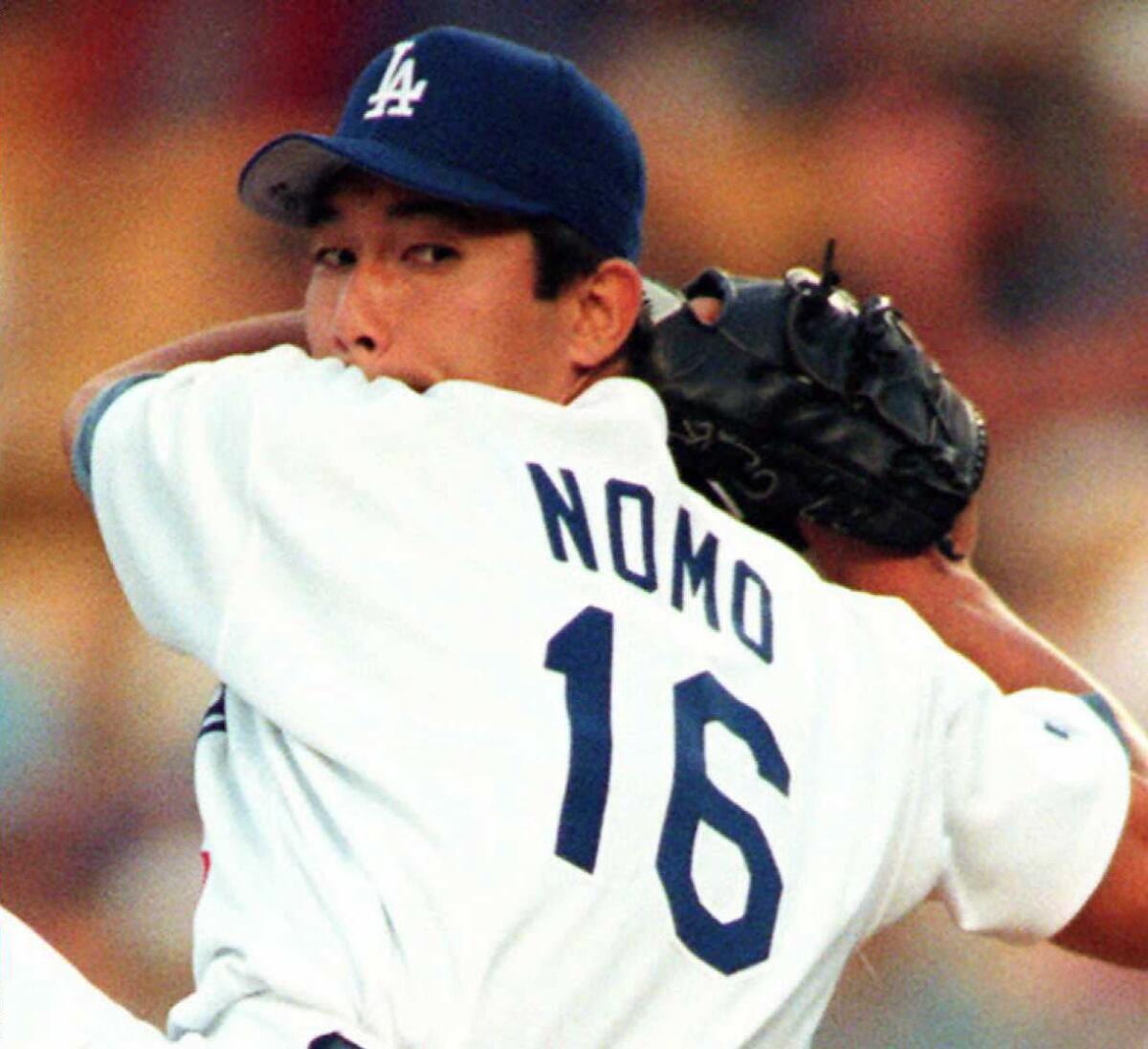

Dodgers snapshot: Nomomania grips L.A. and Japan when Hideo Nomo dominates in 1995

Hideo Nomo pulled into the Dodgers’ spring training complex in Vero Beach, Fla., for the first time in March 1995, hopping out of a minivan just long enough to grab the keys to his dormitory room from a team official and drive away.

About 50 Japanese writers, photographers and cameramen who had staked out Nomo for hours chased it from behind.

Nomo and his interpreter drove slowly around a small loop in front of the team’s headquarters with the media horde in tow, creating a scene right out of a Keystone Kops film.

“They drove around in circles, and the media ran after them until they finally just tuckered out,” said Arizona Diamondbacks team President Derrick Hall, a Dodgers assistant media relations director in 1995. “We watched this go on for about 30 minutes and thought, ‘Oh my goodness, the following this guy has.’ ”

This was but a small taste of the “Nomomania” craze of 1995, when a rookie pitcher from Japan with a quirky delivery and nasty split-fingered fastball helped revive a sport reeling from the cancellation of the 1994 World Series.

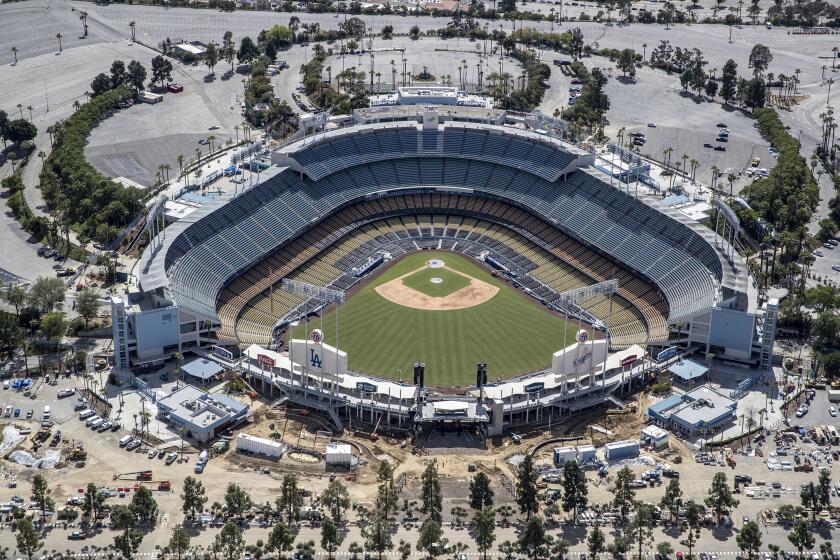

There was something missing at Dodger Stadium on a day that was suppose to be Opening day in MLB.

“It was just a perfect storm when you look back,” Nomo’s agent, Don Nomura, said 25 years later. “There was never an intention to do that. We weren’t timing everything, but it just happened. He rode the wave. MLB took advantage of it, and I think he took advantage of it. So, it was a win-win for everybody.”

With baseball on hiatus because of the coronavirus outbreak, The Times will look back at memorable moments in Dodgers history. Nomomania is a vivid one.

Nomo’s paparazzi-producing potential was clear that February when 15 camera crews, two dozen photographers and several dozen writers packed a Los Angeles hotel ballroom for a news conference to formally introduce the pitcher, who had signed a minor league contract with a $2-million bonus.

The 26-year-old right-hander was in his prime, a star for the Osaka Kintetsu Buffaloes when he left the Japanese Pacific League. He would be only the second Japanese player to appear in the major leagues, following pitcher Masanori Murakami’s brief stint with the San Francisco Giants from 1964 to 1965. But Nomo would pave the way for a generation of Asian players to follow him to the United States.

Nomo’s presence alone assured a huge Japanese media following, and a curiosity factor fueled interest in the U.S.

“We believe MLB is the highest level of baseball in the world,” Eric Karros, a Dodgers first baseman from 1992 to 2002, said during a phone interview. “And here’s someone who, yes, he had success in Japan, but is he going to be successful here? Is that windup going to translate? Will it be more effective? Maybe less effective?”

There would be no mania with mediocrity. Nomo became a world-renowned celebrity and media icon because he was nearly unhittable for long stretches of a strike-delayed 1995 season in which he went 13-6 with a 2.54 earned-run average in 28 starts, striking out a National League-high 236 in 191 1/3 innings.

Nomo started the All-Star game that summer at Texas, becoming the first rookie pitcher to do so since 1981, when Fernando Valenzuela, a 20-year-old Dodgers phenom, was igniting the “Fernandomania” frenzy. Nomo won NL rookie of the year and finished fourth in Cy Young Award voting.

And he did it under a suffocating spotlight, with a constant tug of marketing and community relations demands and a mound of other distractions.

If the MLB season is canceled, the players agree to accept 4% of their 2020 salaries in exchange for service time as if the whole season had been played.

“The guy couldn’t go anywhere, he couldn’t walk anywhere, without a huge contingent of reporters following him around,” Karros said. “It was basically 24/7. The pressure to play in the big leagues, if you’re anybody, is enormous.

“But to intertwine that with, ‘I’m going to a foreign country, and oh, by the way, I have the weight of the country of Japan, as far as succeeding,’ to have all of that on his shoulders? I mean, I’m not sure there are many athletes who have had to deal with that.”

The 6-foot-2, 210-pound Nomo was not overpowering. His fastball topped out at 90 mph. But he had a deceptive delivery and a 78-mph forkball that former Times columnist Jim Murray described as “a split-fingered something-or-other that tends to disappear on the way to the plate.”

Known in Japan as “The Tornado,” Nomo began his windup by slowly raising his arms high above his head before lifting his left leg and twisting his torso until his back faced home plate. Then, he hurtled toward the plate with an explosive delivery that featured the same arm speed for all his pitches.

“I don’t want to see that guy again in my life,” New York Yankees outfielder Luis Polonia told The Times after facing Nomo in a 1995 exhibition. “He got me all confused.”

Nomo had an uneven first month in 1995. He was sharp in his debut May 2, allowing one hit and striking out seven in five scoreless innings at San Francisco, but he gave up seven runs in 4 2/3 innings of his next start at Colorado.

He threw seven scoreless innings, allowing two hits and striking out 14, against Pittsburgh on May 17. Two starts later, he walked seven in a loss to Montreal.

But Nomo hit his stride in June, going 6-0 with an 0.94 ERA in seven starts, striking out 70 in 57 1/3 innings and yielding a .134 average to earn the All-Star start.

“I’ve looked at a lot of videotape on this guy, from a lot of different camera angles, and that split-fingered pitch is unbelievable,” former San Diego Padres Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn told The Times in late-June 1995. “It’s impossible to tell whether it’s a forkball or a heater until that sucker drops a foot at the end.”

Hall said the Dodgers issued an extra 200 media credentials on the nights Nomo pitched, seating reporters in an auxiliary press box usually reserved for playoff and World Series games.

The team held two news conferences — for English-speaking reporters and Japanese-speaking reporters — after every Nomo start. On the first day of every road series, Nomo held a news conference with local Japanese reporters.

Fans clamored for Nomo’s autograph. Everywhere the Dodgers went, local city officials, Japanese corporate executives and dignitaries wanted to meet him.

“He was clearly becoming a rock star,” Hall said. “I had heard the stories about Fernandomania, but this was a level of international stardom I had never seen.”

Letters to the Los Angeles Times sports editor for March 28.

Nomo was even bigger in Japan. Cities and towns across the country televised Nomo’s games on large screens in public places. Work days stopped so fans could watch him pitch. Nomo’s wife, Kikuko, couldn’t venture out of her house in Japan without being hounded by photographers.

Phone lines and fax machines in Nomura’s Tokyo and Los Angeles offices rang nonstop with requests for television appearances, endorsements and magazine and newspaper interviews.

“He was the Michael Jordan of Japan,” Nomura said. “It was chaos. That’s probably the right word for it. It came suddenly and unexpectedly, and it was just unbelievable. Everyone wanted a piece of him.

“There was one company that wanted to get his DNA and put it into a wristwatch. I don’t even know if the company existed — it was probably a bunch of baloney — but we thought it was crazy.”

Dodgers manager Tom Lasorda said Nomomania dwarfed Fernandomania.

“It’s worse, believe me,” Lasorda said before a mid-May night game. “I came to the ballpark at 1:30 today, and there were 15 guys out there with cameras waiting on him. They want to know everything he eats. They’re watching every move he makes. They want to know everything I tell him.”

An Elvis-like aura surrounded Nomo as he entered the stadium in Texas for Monday’s workout before the All-Star game, with dozens of writers, camera crews and photographers chronicling his every move.

“It got to a point where he couldn’t even go to the bathroom without people following him,” Gwynn, who retired in 2001 and died in 2014, said at the time. “I mean, there was a camera crew that literally followed him through the bathroom door. Then, they realized it was a bathroom and turned around. You should have seen their faces. I’ll be telling that story for years.”

Nomo continued to dominate after the All-Star break, going 4-2 with a 1.76 ERA in six starts, including a near-no-hitter at San Francisco in early August.

“A lot of guys, especially left-handed hitters, had trouble against him,” Karros said. “Switch-hitters would sometimes bat right-handed against him. Lefties had a tough time picking up the [forkball]. I don’t know if it was because of the pitch or the windup — it was probably a combination of the two.”

A rough patch in which he allowed 15 earned runs in 16 2/3 innings of three starts fueled speculation Nomo was overwhelmed by distractions.

But he rebounded to go 3-1 with a 2.35 ERA in his final six starts to help the Dodgers win the NL West before they were swept by Cincinnati in the first round of the playoffs.

Nomo, now 51 and in his fifth year as a baseball operations advisor for the San Diego Padres, continued the success in 1996, striking out 17 against the Marlins and pitching a no-hitter against the Rockies at Coors Field. He went on to pitch 12 years in the big leagues, going 123-109 with a 4.24 ERA for seven teams.

But he was never as good as he was in 1995, a season that preceded the arrival of Japanese players such as Ichiro Suzuki, Hideki Matsui, Masahiro Tanaka, Yu Darvish and Shohei Ohtani to the U.S.

“Quite frankly, his success opened up the door for everybody,” Karros said of Nomo. “If he doesn’t have success, I truly believe — while I’m not saying it wouldn’t have happened for more Japanese players — but it doesn’t happen at the speed with which it did.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.