‘The best that ever will be’: Sports broadcasters reminisce about legendary play-by-play man Vin Scully

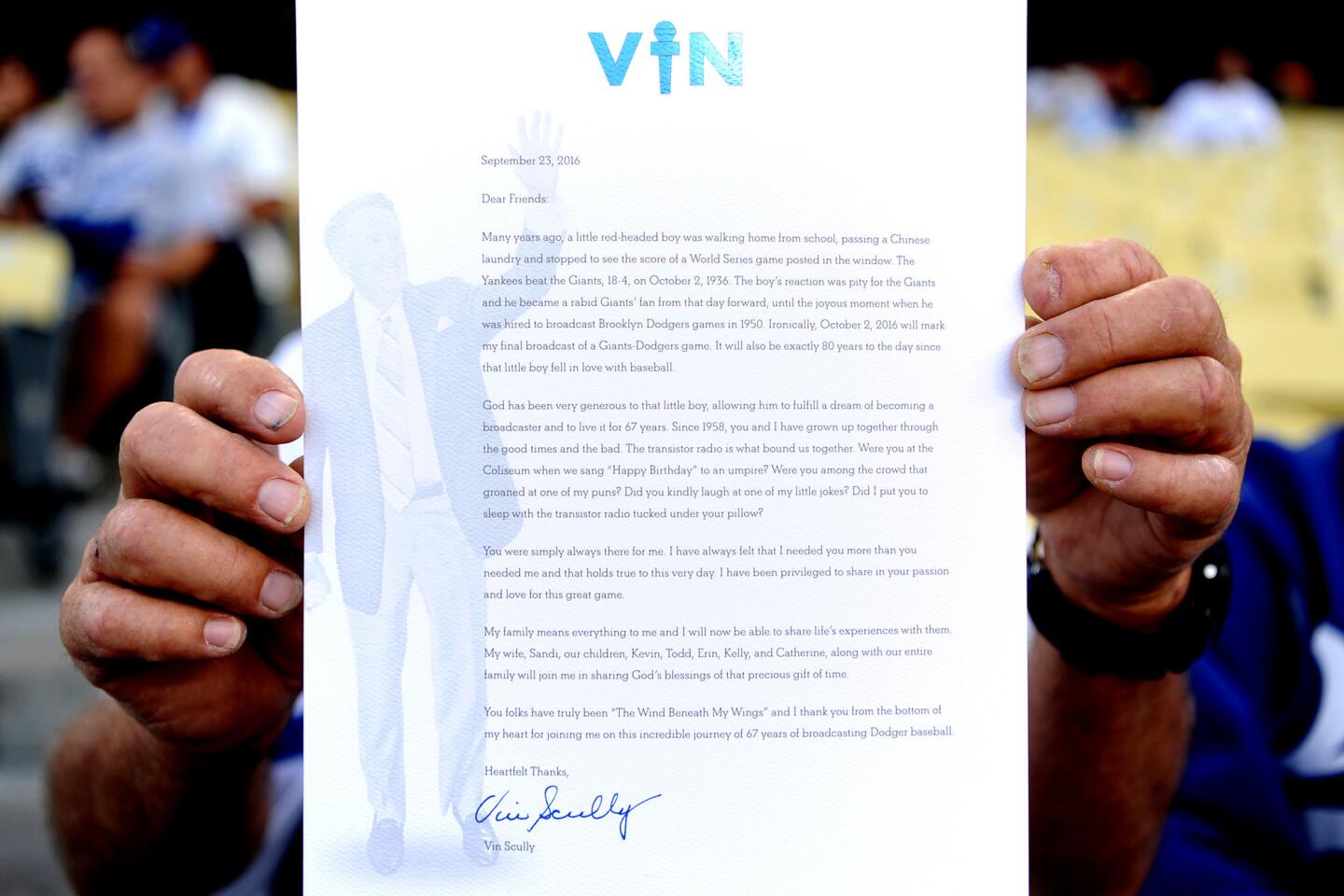

Al Michaels graduated from Los Angeles Hamilton High in 1962 and majored in radio and television at Arizona State, but the lessons that best prepared him for a five-decade career in sports broadcasting began when he was 6 years old in New York City.

That was in 1950, when the Brooklyn Dodgers hired Vin Scully, then 22, to join Red Barber and Connie Desmond in the radio and television booths.

Michaels, who could walk to Ebbets Field from his Brooklyn home, listened to Scully through elementary and middle school.

Michaels’ father took a job in Los Angeles and moved the family there in 1958, the same year the Dodgers migrated west, so Michaels was able to listen to Scully through high school and college.

Michaels got to know Scully personally during a pair of three-year stints as a play-by-play man for the Cincinnati Reds and San Francisco Giants in the 1970s, and he often tuned in to Dodgers games when he returned home from his wide array of assignments for ABC and NBC over the next 40 years.

“I have spent my entire life listening to Vin Scully. He was the guy who taught me everything I know about baseball, who was in my ear when I began my career,” Michaels, 71, said. “It was like being in a classroom with Socrates teaching you philosophy.”

That point was driven home — quite literally — in August when Michaels tuned in to a Dodgers-Colorado Rockies game that he recalled as “kind of non-descript,” with one notable exception: the man describing the action on the radio.

“Vinny made that game so interesting for me that as I get off the freeway and drive to the house, I’m idling the engine in my driveway because I want to hear him finish a story,” Michaels said. “And this is 67 years into his career.”

::

Jon Miller, in his 20th season as the Giants’ play-by-play man, had a similar car-radio experience with Scully after his senior year of high school, though his was more of an epiphany.

Miller was a huge Giants fan growing up in the Bay Area, so he hated all things Dodgers. He knew of Scully because he heard some Dodgers games on KFI, which had a signal strong enough to reach Northern California at night. But Miller preferred the “bye-bye baby” home-run call of San Francisco’s Russ Hodges over anything Scully had to offer.

That changed one summer evening in 1969 when Miller was driving home from Eugene, Ore., after a visit with his grandmother.

Miller, 64, was an aspiring broadcaster by this time, so when he picked up a Dodgers game, he committed to listening to it start to finish with a more discerning and objective ear.

“I realized that, listening to Vin very closely, uninterrupted in the car, how great he was, how I felt like I could see everything that was happening in the game, and how he had stories that always seemed apropos to what just happened in the game or a player who was batting,” Miller said.

“The stories themselves were extremely fascinating or funny, or both, and they never got in the way of the action. He weaved everything together so well. I was thoroughly entranced and entertained and was sad when the game ended. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, that is the way it’s done.’ ”

::

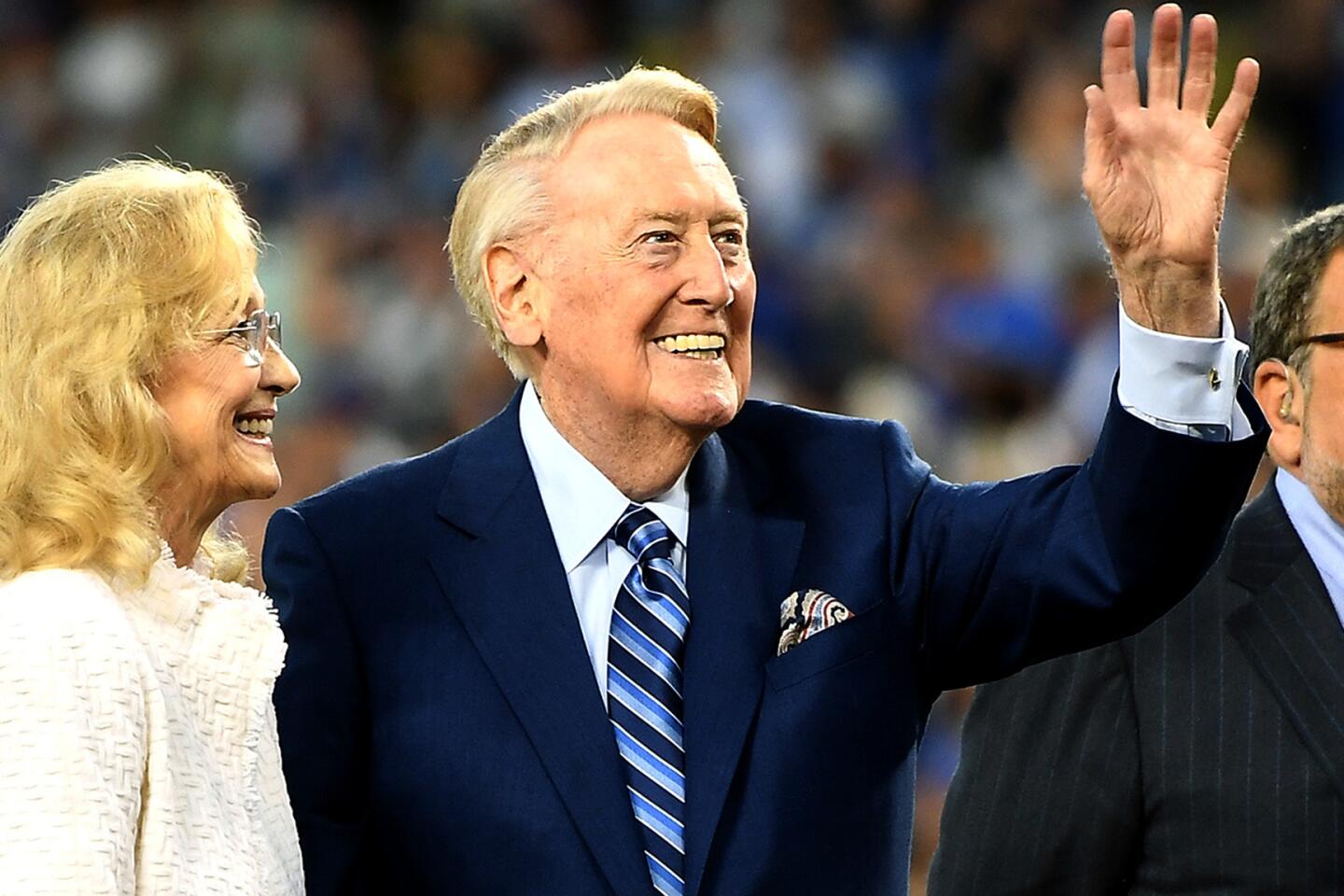

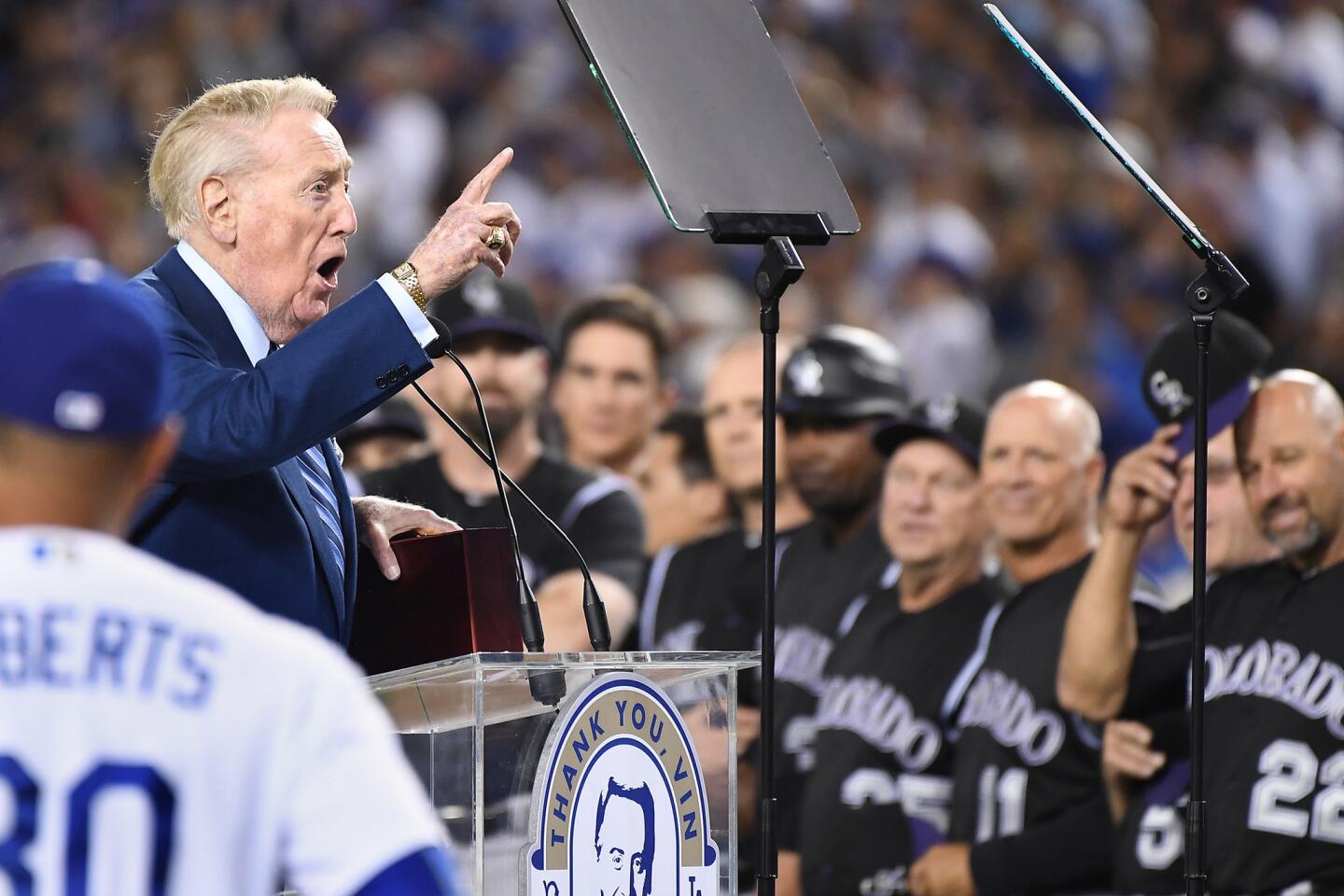

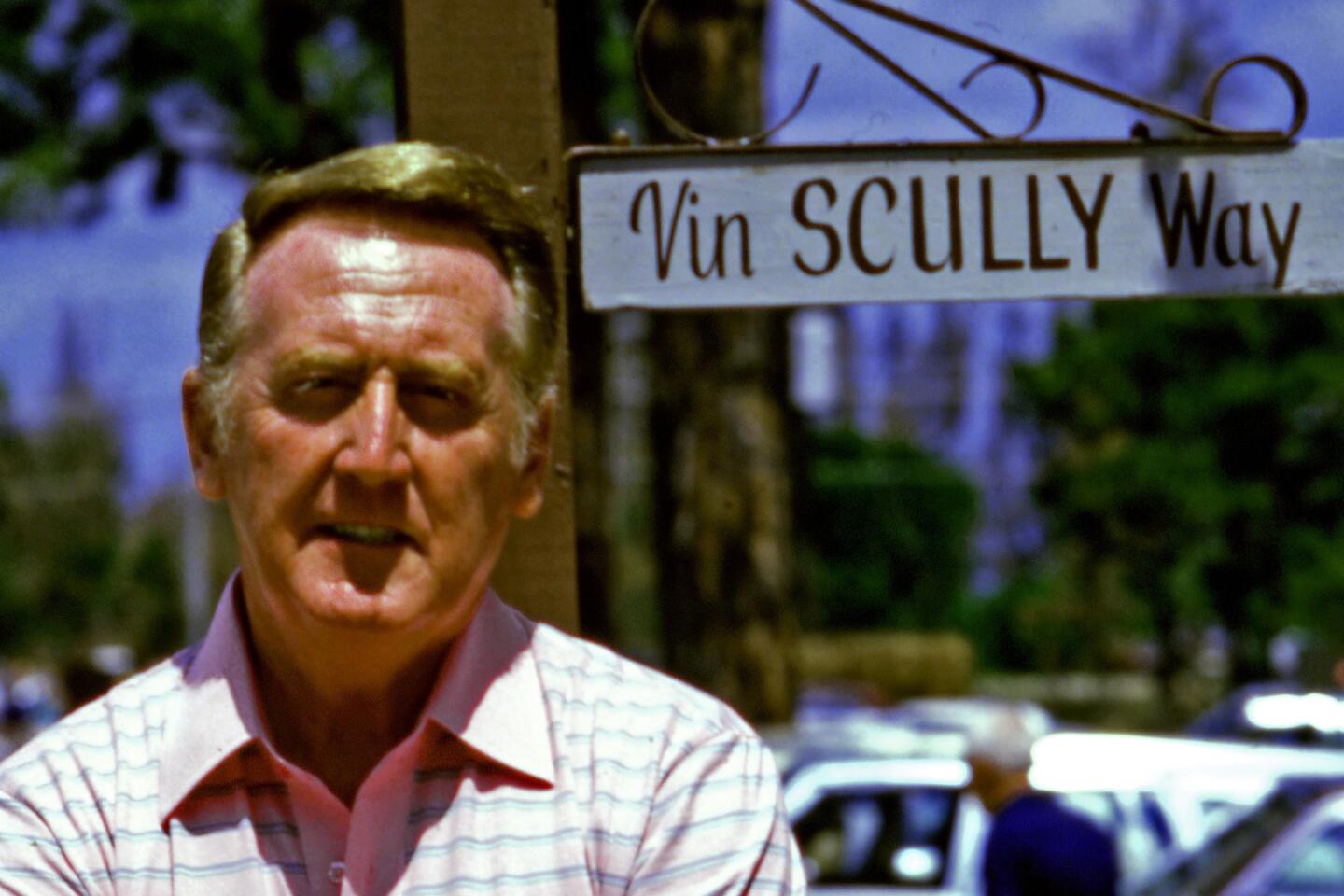

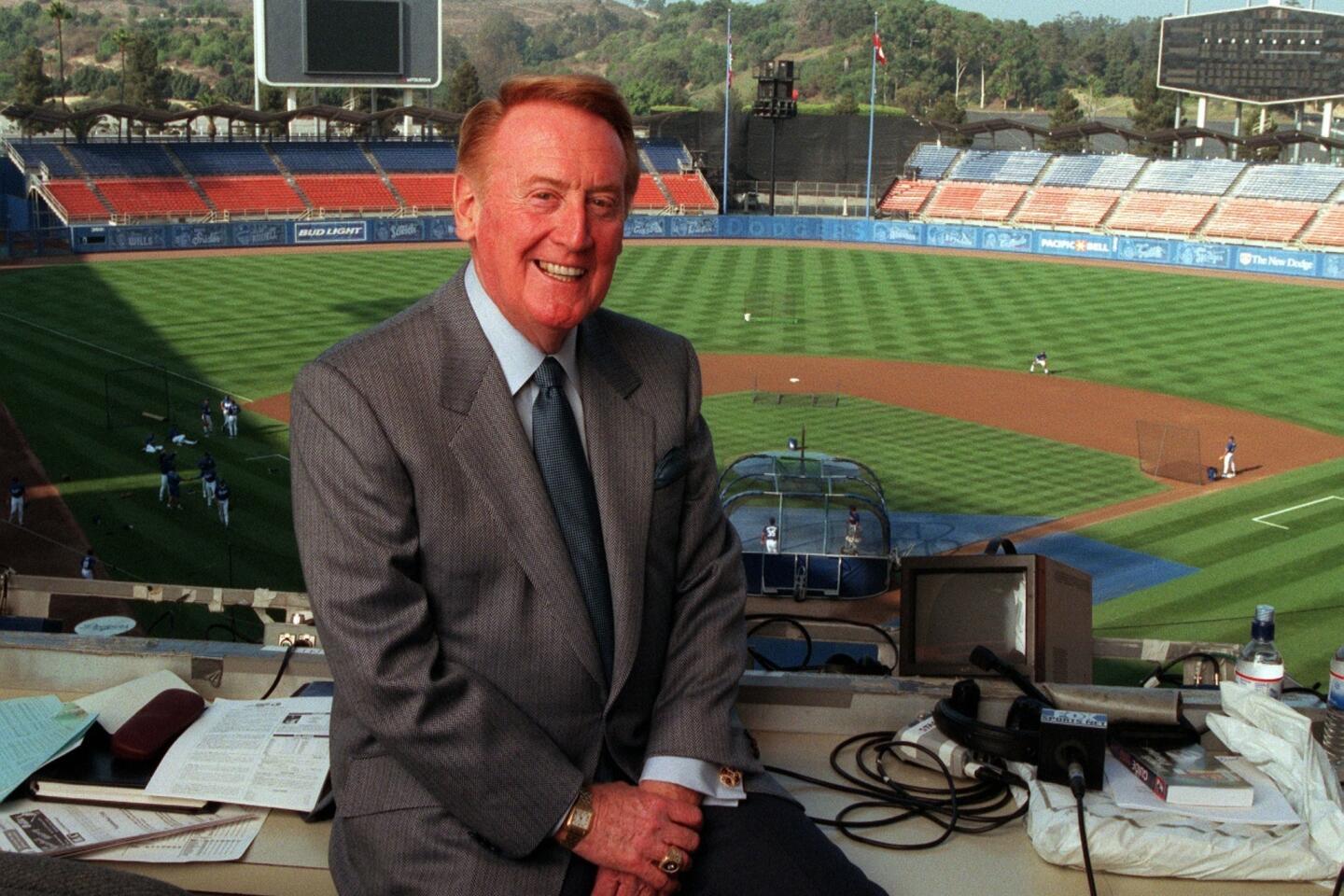

Bob Miller has spent 43 years as the Los Angeles Kings’ play-by-play man, and the speed and pace of his sport don’t afford the same story-telling opportunities Scully had during his 67-year career, which will end in San Francisco next weekend. But Miller, 77, has tried to infuse Scully into his hockey broadcasts.

“Vin has that knack of bringing you into the game, and a lot of that is timing,” he said. “I learned that from him, and all announcers can learn from that — when to be excited, when to settle things down, when to let the audience breathe a little bit, when to bring them right into the action with your voice and the crowd noise.

“So many times on big plays, he would describe the action, then not talk for 20 or 30 seconds, a minute. If the crowd is going crazy, that brings your audience right into the ballpark. He’s just a master of that.”

::

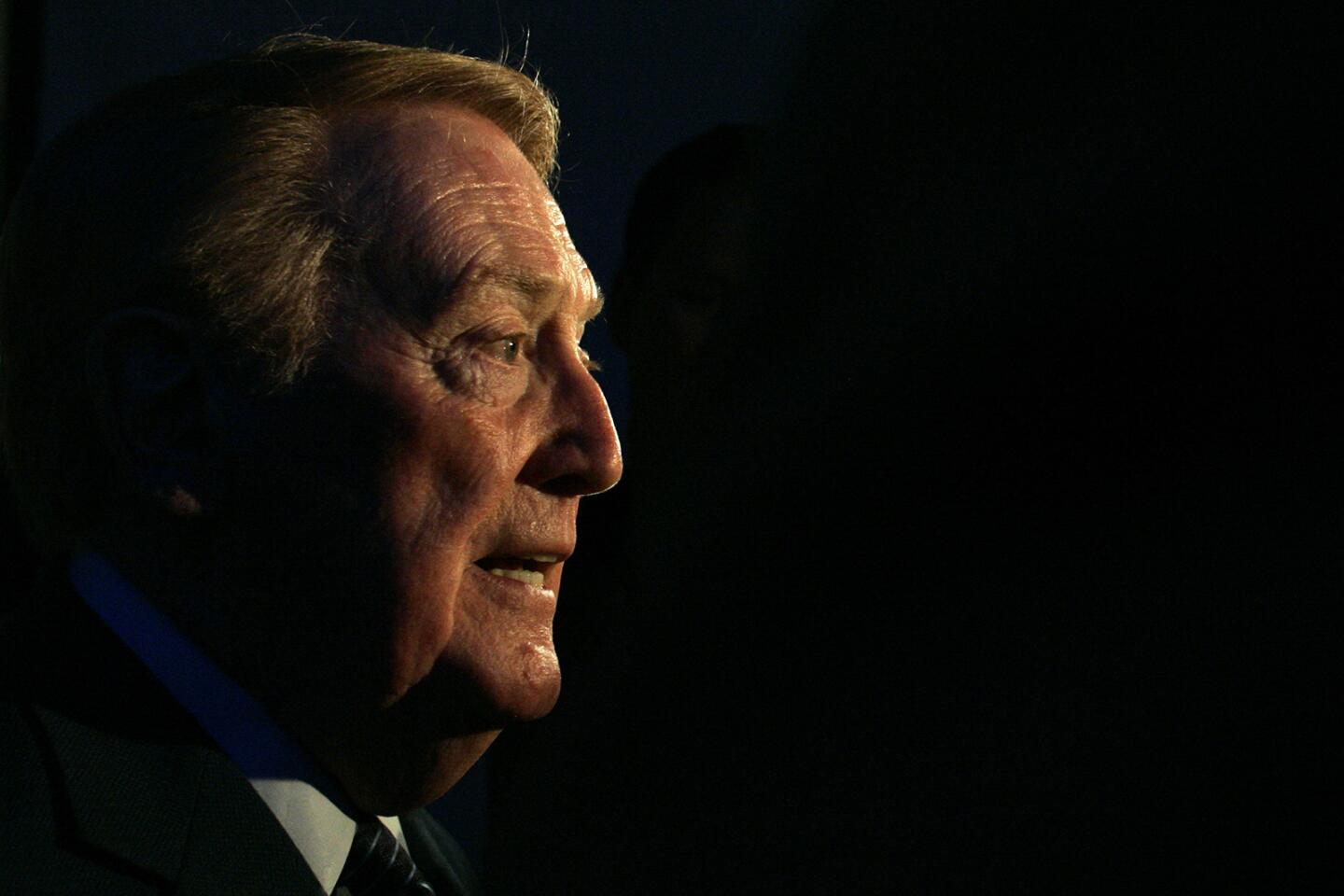

Few moments better illustrate Scully’s mastery of the microphone than his call of Hank Aaron’s 715th home run to break Babe Ruth’s record on April 8, 1974. The call itself was pretty straightforward:

“Fastball, it’s a high drive to deep left-center field. Buckner goes back, to the fence. It’s gone!”

Scully then let the roar of the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium crowd fill the airwaves for 27 seconds before launching into a famous Scully soliloquy:

“What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol.”

Jon Miller was familiar with former Braves announcer Milo Hamilton’s call of Aaron’s homer, but he didn’t hear Scully’s full call until 1999, when TBS did a 25-year anniversary documentary of Aaron’s pursuit of Ruth.

“It gave me chills. It made me a little teary-eyed because he transcended sports broadcasting at that point,” Miller said. “He put the significance of what Henry Aaron, a black man, had just done in a larger context. It was an extemporaneous moment, off the top of his head, and it was just so true and perfect.

“I’m sure if Vin had been a news broadcaster or an anchorman, he would have been the Walter Cronkite of his time, the guy with a command of the language who you’d want covering a political convention or election. He’s the best there’s ever been broadcasting a baseball game, and the best that ever will be.”

::

As spontaneous as Scully’s dramatic calls are, the anecdotes and human-interest stories he threads through the action are often the result of his extensive pregame research of players, trends and statistics and his remarkable recall.

“He is still the first guy to the ballpark. Every time we go to Dodger Stadium, he is there before I am,” said San Diego Padres play-by-play man Dick Enberg, who is also retiring after a distinguished 60-year career in sports broadcasting.

“His mind is incredible. I’m amazed at his storytelling and his capacity to remember small detail. He’s just brighter than the rest of us.”

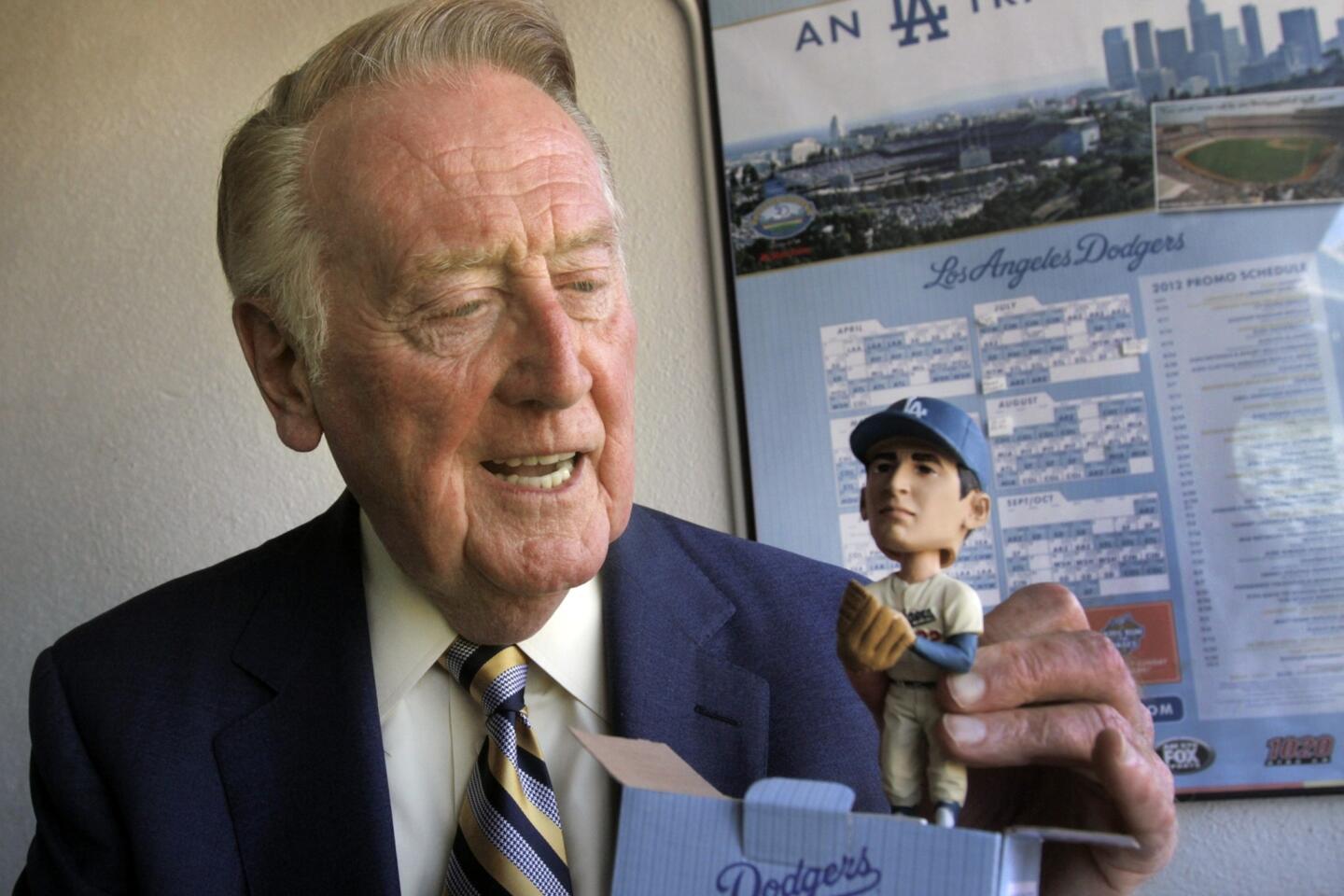

When Scully began calling the Game of the Week for NBC in 1983, exposing his mellifluous voice and descriptive style to a wider audience, it spawned a generation of Scully clones.

“You’d receive tapes from young guys in the minor leagues who sound like Vinny, using Vinny’s distinctive little phrases like, ‘Three runs on half-a-dozen hits,’ ” Jon Miller said. “He was the best, and it only made sense to try to sound like that.”

Michaels was an admitted Scully Wag, from his first gig as a minor league play-by-play man in Hawaii in 1968 through his early days with the Reds and Giants.

“I had a lot of Scully in me — the pacing, the rhythm, how you construct the game, weaving the stories in,” Michaels said. “Vinny was my guide, my professor.”

What makes Scully so special, Fox Sports broadcaster Joe Buck told The Times in July, is his “incredible ability to make every viewer or listener feel like he is talking to them specifically.”

Michaels felt that connection as a child in Brooklyn and as a young man in Los Angeles, and he still felt it some 50 years later in his driveway in August.

Scully drew Michaels into that Dodgers-Rockies broadcast, and Michaels sat in his car with the radio on, not wanting to let Scully go. It’s a feeling shared by a nation of baseball fans who want to hold onto Scully forever.

“Vinny has this amazing ability to see thousands of games, everything that could possibly be done, and yet still have what I would call a sense of wonder about the game,” Michaels said. “If you lost that, I think you’d lose everything. That’s never happened to Vinny. People say, ‘Well, who’s gonna replace him?’

“Nobody.”

Twitter: @MikeDiGiovanna

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.