Remembering the Dodgers’ Bob Welch, weaver of World Series dreams

Lives are never meant to be defined by single moments, but sometimes they’re just so overwhelming they sear themselves deep into the memory, impossible to separate from the individual.

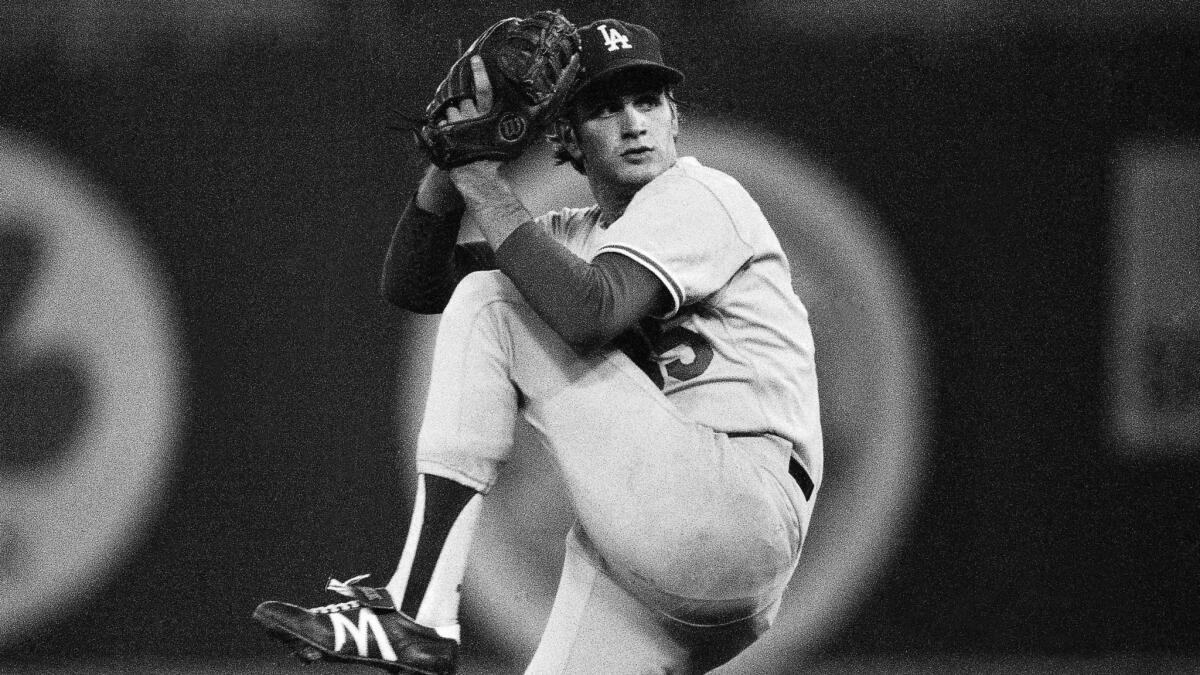

Bob Welch’s life was made up of many memorable moments, yet for most baseball fans the first image to come screaming back is of that fearless young kid on the mound in the World Series, staring down mighty Reggie Jackson.

Welch was only 21, with a face that looked like it had yet to meet a razor. He had all of 23 regular-season major league games behind him. But the former No. 1 pick threw the kind of heat that left vapor trails and had nerves of carbon steel.

It was a classic sporting moment, that special kind that builds the way only baseball can truly offer. Game 2 of the 1978 World Series, the Dodgers clinging to a 4-3 lead over the Yankees in the top of the ninth with two outs, night having fallen at Dodger Stadium.

And there was Jackson, with all his New York swagger and arrogance, with two runners on and the kid on the mound for the Dodgers. It was the first World Series I ever covered, and the moment was electrifying. The confrontation built with each pitch and the count went full.

Then on his ninth pitch to Jackson, king of the dramatic moment, Welch fired a high blazing fastball that Jackson swung under, his body corkscrewing, the sellout crowd erupting with the strikeout. Jackson walked off in anger, flashing a disbelieving look back at Welch before firing his bat against the dugout wall.

Welch went on to pitch 17 seasons in the major leagues for the Dodgers and A’s, and though he would fill his career with many unforgettable moments, it would be forever difficult to surpass that indelible World Series theater.

As a single World Series moment, it might only be surpassed in Dodgers lore by Kirk Gibson’s famous home run.

Welch died of a heart attack Monday night at his home in Seal Beach, the Dodgers said Tuesday. He was only 57.

He was born Robert Lynn Welch on Nov. 3, 1956, in Detroit. Grew up in Ferndale, about 12 miles southeast of Detroit. Welch was a pitching standout for three years at Eastern Michigan when the Dodgers made him the 20th overall pick in the 1977 draft.

One year after his sensational rookie season -- Manager Tom Lasorda compared him to Don Drysdale -- the Dodgers moved him exclusively to the rotation and he flourished. In 10 years with the Dodgers, he went 115-86 with a 3.14 earned-run average. In 1988 he was traded to the A’s and was actually the starting pitcher in the only game the A’s won against the Dodgers in that World Series. Rick Honeycutt, current Dodgers pitching coach, got the win.

The next year he was scheduled to be the Game 3 starter for the A’s against the Giants when the 1989 earthquake shook San Francisco and postponed the game for 10 days. Given the additional time, A’s Manager Tony La Russa returned to his opening starters, Dave Stewart and Mike Moore, for Games 3 and 4 and rescheduled Welch for Game 5. The A’s swept the Giants and Welch never did pitch in the series.

The next year, however, he went 27-6 with a 2.95 ERA and won the American League Cy Young Award. He was 33. Welch remains the last major leaguer to win at least 25 games in a season.

Welch always seemed friendly and easy-going, but he was not without his demons. In 1982 he wrote “Five O’Clock Comes Early: A Cy Young Award-Winner Recounts His Greatest Victory” with New York Times columnist George Vecsey. It chronicled his addiction to alcohol.

It could not have been an easy book to publish, detailing how he would sometimes show up drunk to games. The Dodgers sent him to rehab in 1980 and Welch said the recovery program stuck.

He retired after the 1994 season, and in many ways still had the youthful look of the boy who slays the Jackson dragon. He was the Diamondbacks’ pitching coach when they won the World Series in 2001, his legacy still tied to the World Series.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.