Judge in Angel Stadium land deal hearing expects losing side to appeal

If the city of Anaheim violated the state’s public transparency laws in negotiating the Angel Stadium land sale, must the sale be nullified?

Orange County Superior Court Judge David Hoffer wrestled with that question Wednesday, hearing from attorneys from the city and from the citizens group that sued to stop the deal. Hoffer said he expected to take about 30 days to issue his decision and said he anticipated the losing party could appeal.

“That’s where I think it’s going,” Hoffer said.

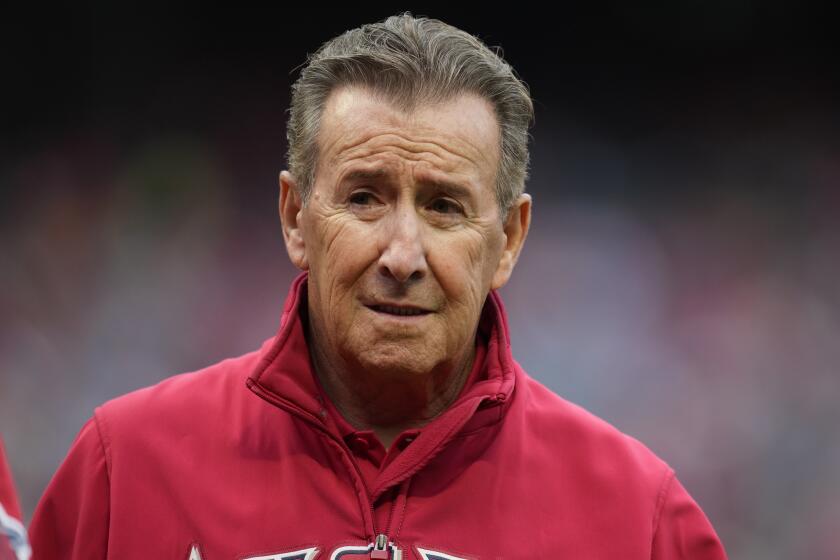

An appeal could further delay the closing of a deal which the Anaheim City Council approved in 2019. Under the deal, a company controlled by Angels owner Arte Moreno would buy the stadium and surrounding parking lots for $150 million in cash, then put up homes, shops, restaurants, offices and hotels around a new or renovated ballpark.

The development agreement allows Moreno’s company up to 15 years after closing to complete construction of the project’s flagship park, up to 25 years to complete the housing and up to 30 years to complete the hotel and other commercial developments.

Attorneys for the Angels suggested in court filings that the deal could stand even if the city violated the law because the team assumed a contractual obligation and spent money implementing the deal in good faith before a third party challenged it. The only attorneys that spoke during Wednesday’s hearing were those representing the city and the citizens group.

What happens if a judge decides the sale of Angel Stadium broke the law? Here’s the breakdown of what could happen next.

Kelly Aviles, the attorney for the group, told Hoffer she believes the particular violations she alleges require the deal to be invalidated. But she acknowledged violations of the Brown Act — the state law that generally requires public business be conducted in public — sometimes result in a judge simply finding that the law was broken, with the option of mandating safeguards against a future violation.

Thomas Brown, an attorney for Anaheim, said the city did not violate the law. Even if the city did violate a provision of the law forbidding council discussions outside of council meetings, Brown said, the law does not require the deal be invalidated.

“We’re not saying, ‘This is a “Get Out of Jail Free” card,’ ” Brown said.

The fundamental allegation in the lawsuit is that Anaheim circumvented the Brown Act by deciding to sell the land behind closed doors, rather than in a public meeting, and used a negotiating team to make key decisions about how to proceed in private, beyond the “price and terms of payment” exception allowed by law.

Brown said the city did not have a negotiating team per se, instead using then-city manager Chris Zapata as a point man to assemble the mayor, the city attorney, city staffers and outside consultants as needed, and said Aviles’ assertion that the mayor and city attorney were part of a three-man negotiating team was “this fiction.” Aviles, asked by Hoffer for evidence to support her assertion, cited in part an Orange County Register op-ed in which Mayor Harry Sidhu wrote that he was “part of the negotiating team.”

Zapata and City Councilman Jose Moreno submitted sworn declarations saying the decision to sell the land was made behind closed doors. City Attorney Rob Fabela submitted a sworn declaration saying the discussion in that closed-door meeting revolved around an appraisal, and Brown said Aviles “was inventing” an alleged legal requirement that the city was obligated to talk about the merits of selling as opposed to leasing the land in public.

“The driving factor here was fair-market value, not sale or lease,” Brown said.

The Kennedy Commission, an Irvine-based housing advocacy group, warned the city of Anaheim that its proposed Angel Stadium sale would violate the law.

Aviles expressed skepticism that a detailed purchase proposal from the Angels had surfaced without the city making a decision to sell the land.

“You mean there was never any discussion about whether we would be willing to sell the property to the Angels and yet they gave us a concrete proposal?” Aviles asked. “That doesn’t ring true.”

Aviles said the city had “an intent to keep this a secret” rather than “having these discussions in open session.” Brown said any alleged violation of the law would have been alleviated in public hearings — one before the council approved the purchase agreement, another before approval of the development agreement — where he said citizens had a “full and fair” opportunity to comment.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.