Eric Kay found guilty of supplying drugs that led to death of Angels’ Tyler Skaggs

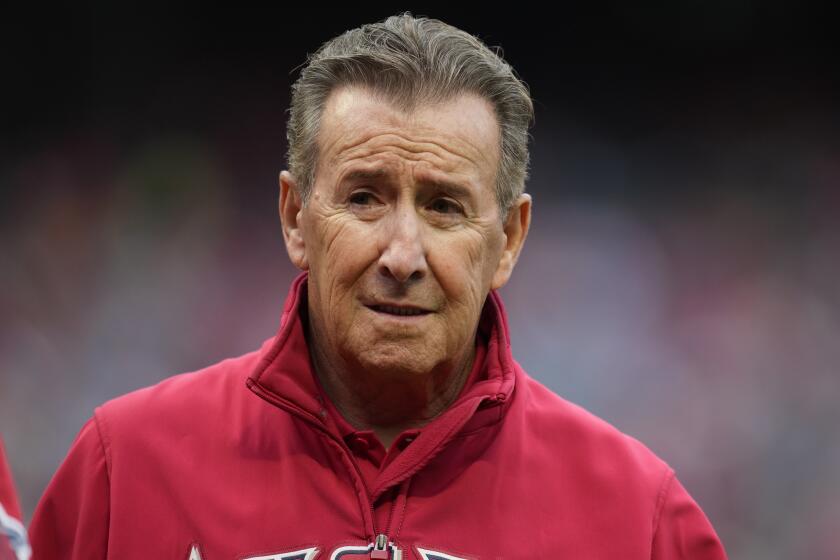

FORT WORTH — A former Angels communications director was found guilty Thursday of distributing fentanyl and giving Tyler Skaggs the drugs that caused the Angels pitcher’s death in a suburban Dallas hotel room in 2019, concluding a trial that yanked Major League Baseball to the center of the national opioid crisis.

Eric Kay, 47, faces 20 years to life in a federal prison and up to a $1-million fine. His sentencing is scheduled for June 28.

The 12-person jury listened to closing arguments in U.S. District Court on Thursday morning before reaching a verdict after less than 90 minutes of deliberation. In addition to finding Kay guilty of committing the crimes in Texas, the jury agreed with the government that “but for” the fentanyl, Skaggs wouldn’t have died.

With Kay convicted, the attention will shift to the civil lawsuits the Skaggs family has filed against the Angels in Texas and California.

“We are very grateful to the government and the jury for seeing this important case through to the right verdict,” the Skaggs family said in a statement. “Tyler was the light of our family. He is gone, and nothing can ever bring him back. We are relieved that justice was served, although today is a painful reminder of the worst day in the life of our family.”

Kay’s demeanor did not shift when Judge Terry R. Means read the verdict. His hands were folded on the table in front of him. He remained stoic. His family and friends in the gallery appeared to be in shock. Skaggs’ mother, Debbie Hetman, slumped and cried. She and Skaggs’ wife, Carli, later hugged and cried together, rejoicing just feet away.

Moments later, Kay spoke in court for the first time since pleading not guilty last week. His emotions did not waver.

Eric Kay was found guilty of supplying the drugs that killed Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs. Now lawsuits and an investigation by MLB take the spotlight.

“I’m sorry, but I have to order you taken into custody,” Means said.

“I understand, your honor,” Kay said.

U.S. marshals asked Kay to take off his suit jacket and tie, and remove all items from his pockets. One official asked him what something was. Antidepressants, Kay answered. One of Kay’s attorneys gave his mother, Sandy, his belongings as he was handcuffed. His sister, Kelly, left the courtroom in tears once her brother was escorted out.

“We thought there were many reasons to doubt the government’s case,” said Reagan Wynn, one of Kay’s two attorneys. “This is a tragedy all the way around. Eric Kay is getting ready to do a minimum 20 years in federal penitentiary, and it goes up from there. And Tyler Skaggs is gone. It’s a tragedy. There’s no winners in any of this. It’s a sad day.”

Skaggs was found dead in Room 469 of the Hilton Southlake/Dallas Town Square just after 2 p.m. CDT on July 1, 2019. He was 27. The Angels had flown to Texas from Long Beach Airport the previous night to begin a series against the Texas Rangers that day.

An autopsy report concluded that Skaggs, who choked on his vomit, had fentanyl, oxycodone and alcohol in his system. More than a year later, Kay, who had worked for the Angels since 1996, was charged with conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute fentanyl “beginning in or before 2017.” Kay turned himself in on Aug. 7, 2020.

In October 2020, a federal grand jury indicted Kay on two felony counts: the previous conspiracy charge and with “knowingly and intentionally” distributing the fentanyl that led to Skaggs’ death. In November 2021, six days before Kay’s trial was scheduled to start, prosecutors secured a superseding indictment that added oxycodone to the original conspiracy distribution charge.

After six delays over 14 months, the trial began Feb. 10. Over the next week, the government made its case, in part by calling four former Angels player to testify that they had received drugs from Kay between 2017 and 2019. The defense began and rested its case with six witnesses Wednesday.

All along, the government had to not just convince the jury that Kay committed the crimes but that it was “more likely than not” they occurred in Texas.

More people filled the gallery for closing arguments Thursday morning than in the trial’s first eight days. A sketch artist sat in the first row, on the left side facing the proceedings, with a clear view of Kay. The judge, after apologizing for his congested throat, read jury instructions for 23 minutes. A large whiteboard with a timeline the prosecution constructed throughout the trial stood near the jury box.

Kay observed the closing arguments from where he has since first entering Room 205 last Tuesday: at the far end of a wooden table across from the jury, next to his attorney Michael Molfetta, for the most part shielding emotion as details of his drug addiction were unearthed and dissected one more time.

Assistant U.S. Atty. Lindsey Beran was given the floor first. She began her 28-minute argument by contending that Kay, and only Kay, could’ve given Skaggs the drugs that killed him. She asserted Kay gave Skaggs the drugs in Texas. She said Kay was Skaggs’ only source for blue 30-milligram oxycodone pills — and a source for at least six other former Angels players over three years. Beran contended that Kay gave Skaggs the blue pill that was found in his room after his death.

She argued Kay was guilty of the conspiracy count without even giving the drugs to Skaggs — by lying to the Southlake Police Department on July 1 about seeing Skaggs in his hotel room the previous night when he later admitted he went to Skaggs’ room; by contacting Ashley Smith, an alias for a California woman who the government alleged sold Kay the pills that killed Skaggs, later that night; and by telling Matt Harvey, who testified receiving a blue oxycodone pill from Kay on June 30, that they should “stick together” when the two saw each other two days later in Texas.

Beran pointed out that to be found guilty of the second charge, Kay didn’t have to know the drugs he gave Skaggs contained fentanyl. She pointed to the text exchange between Kay and Skaggs on the afternoon of June 30 — when, the prosecution argued, Kay bought drugs from Smith.

“How many?” Kay asked. “Just a few, like five,” Skaggs replied. “Don’t need many.”

She argued that texts later that day showed Kay was the only person Skaggs saw after he checked into his hotel room at 11:43 p.m. CDT. Four minutes later, Skaggs texted Kay his room number — 469 — and told him to “come by.” Kay responded, “K,” three minutes later. The last text from Skaggs’ phone was sent to his wife at 12:02 a.m.

Beran cited Harvey’s testimony, emphasizing that Harvey, under oath, said he gave Skaggs pink pills in early June, but not any blue oxycodone pills. She said Skaggs’ Google search for KP56 pink pills on June 7 corroborated Harvey’s story.

She recalled testimony from three of the former Angels players — Harvey, Cam Bedrosian and Blake Parker — who all said “it could’ve been me.”

“There was one person who went into that room and gave Tyler Skaggs fentanyl,” Beran said. “That person was Eric Kay, and Tyler Skaggs is dead because of that.”

Molfetta vigorously countered over 30 minutes, emphasizing that the government wanted the jury to make too many assumptions.

He rhetorically asked the jury why Kay would give leave an oxycodone pill for Harvey at his locker at Angel Stadium and wait to give Skaggs his pills in Texas. Kay had access to Skaggs. The player, Molfetta repeated, wasn’t “an emperor.” Kay, according to Molfetta, didn’t hide from distributing and abusing drugs, but he did it only in California.

At the Eric Kay trial Tuesday, four former Angels testified to receiving oxycodone pills from the team’s former communications director.

He reiterated the defense’s argument that Chris Leanos, a drug dealer and Skaggs’ close friend, could’ve dropped off the pills to Skaggs before the Angels traveled to Texas after Skaggs had asked if Leanos knew of anyone who could get him pills a week or two earlier. Leanos said he sold various drugs but not oxycodone, and Molfetta said he found that difficult to believe from a person who was given immunity for life and admitted to “250 drug transactions” in the last three years.

Molfeta argued that evidence showed that Skaggs’ stepbrother, Garet Ramos, deleted text messages from Skaggs’ phone when he was in possession of it at the Southlake police station July 1. He said the phone was further tampered with over the following weeks because video of Skaggs’ memorial was found on it.

He wondered why the government didn’t try to find Smith, who the evidence showed, he said, “was handing this stuff out like candy.”

“They want you to clean up California’s mess,” Molfetta said.

He asserted the government didn’t go after Smith because “there’s no cachet.” He argued the government wanted to make a statement, spending thousands of dollars in taxpayer money for expert witnesses to push a narrative. “Do you think if Eric Kay was dead,” Molfetta said, “you’d be here?”

Molfetta wondered: When “does a grown man” living a life of “complete luxury” take responsibility for his own actions? “A young man died because of his demons,” Molfetta said.

On Thursday, another man found out he’ll spend at least the next two decades in prison.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.