Albert Pujols’ greatness was evident from the start of his career

The exchange is vivid in the mind of Peter Gammons two decades later, the veteran ESPN baseball analyst still marveling at the prescience of it all.

Gammons was in Jupiter, Fla., in late March 2001 for an interview with Mark McGwire, the St. Louis Cardinals slugger who was approaching the end of a 16-year career in which he would hit 583 home runs.

As he greeted McGwire in front of the first-base dugout on that sunny spring morning, a constant thwack could be heard from the nearby batting cage, where a 21-year-old Albert Pujols was rifling line drives all over Roger Dean Stadium.

“He said the guy you should be interviewing is the guy there in the cage, the rookie,” Gammons said, recalling his conversation with McGwire. “He’s going to the Hall of Fame, no doubt.”

Albert Pujols was the best player in baseball when the Angels signed him in 2011, but he couldn’t match his accomplishments from his St. Louis days.

Pujols was a virtual unknown at the time, a strapping youngster full of potential but in his first big league camp and just two years removed from his 13th-round selection in the 1999 draft.

Sure, he was on the cusp of the major leagues after touching triple-A in 2000, but a Hall of Famer? Pujols wasn’t even a lock to make the team that spring, let alone win a starting job. What would possess McGwire to set the bar so high for a guy who hadn’t even taken a major league at-bat?

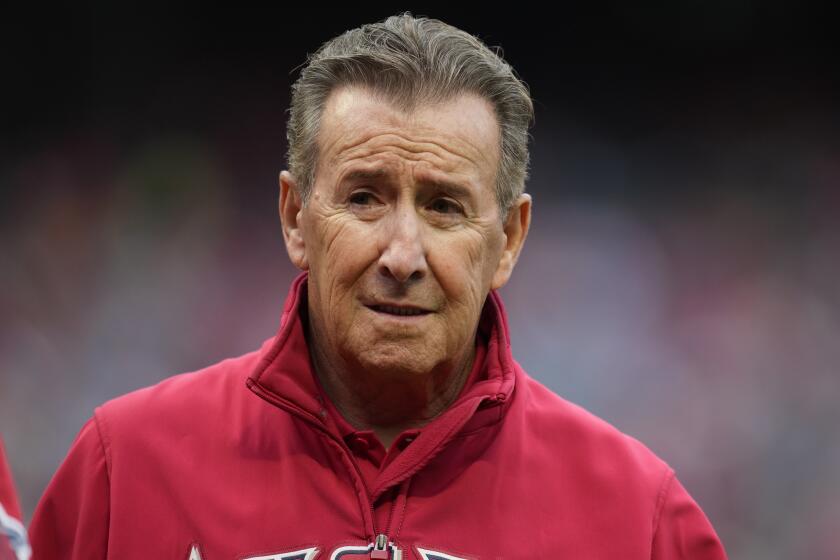

“To me, it’s about the blinders,” McGwire said Thursday, after the 41-year-old Pujols was designated for assignment by the Angels in the final year of a 10-year, $240-million deal. “There were no distractions. Most young kids get distracted in their first big league camp. You see a lot of young kids struggle.

“There’s so much going on, so much pressure,” he said. “The media, fans, expectations. He didn’t have any of that stuff. There was no awe in anything for him. He had the blinders on. He knew exactly what he wanted to do. He knew how to get ready.”

That drive, determination and work ethic, that single-minded focus on preparation and perfecting his craft, laid the foundation for a 21-year career in which Pujols amassed 3,253 hits, 667 homers — which ranks fifth on baseball’s all-time list — and 2,122 RBIs.

Five years after his playing career officially ends, Pujols, who won three National League most valuable player awards and two World Series titles with the Cardinals from 2001 to 2011, will be enshrined in Cooperstown, N.Y., alongside baseball’s other immortals.

Just as McGwire predicted.

Mark McGwire earns his chance for a new path with Dodgers

“A lot of guys have a good couple of months, maybe a good year, but they can’t repeat it,” McGwire said. “Look at what Albert did. The first 10 years of his career is the best [decade-long run] in the history of the game. Nobody has ever put the spikes on and done what he has done.”

Though Pujols notched his 3,000th hit and 500th and 600th homers as an Angel, his tenure in Anaheim was a disappointment, marked by a dramatic drop in production, a series of lower-body injuries, one meager postseason appearance and zero playoff wins.

But as a Cardinal, Pujols produced one of the best decade-long stretches in baseball history, one that probably would have garnered Hall-of-Fame honors if he had retired after 2011.

Pujols hit .331 with a 1.050 on-base-plus-slugging percentage, 408 homers, 1,230 RBIs, 1,186 runs, 426 doubles, 914 walks and 646 strikeouts from 2001 to 2010. According to Baseball Reference, he accumulated 83.8 wins above replacement in his first 10 seasons, second only to Ted Williams among position players.

The only players to post what could be considered better 10-year stretches are Babe Ruth, who hit .355 with a 1.228 OPS, 467 homers and 1,338 RBIs from 1920 to 1929, Alex Rodriguez (.304, .982 OPS, 454 homers, 1,275 RBIs from 1998 to 2007), Barry Bonds (.315, 1.169 OPS, 444 homers, 1,083 RBIs from 1995 to 2004) and Jimmie Foxx (.335, 1.086 OPS, 413 homers, 1,416 RBIs from 1929 to 1938).

“It was historic,” Chicago White Sox manager Tony La Russa, who managed Pujols in St. Louis, said on Friday. “He was, and he is, one of the game’s great, winning competitors.

“Watching it, we were all just amazed. And the more success he had and the more money he put in the bank, the hungrier he got, which is a testament to his character and commitment.”

And to think, if not for Bobby Bonilla’s hamstring injury in the last week of spring training in 2001 — and some prodding of La Russa by McGwire — Pujols might not have opened 2001 with the Cardinals.

Bonilla hit .389 with four homers that spring and was set to start in left field. His March 24 injury opened the job for Pujols, who hit .329 with a 1.013 OPS, 37 homers, 47 doubles and 130 RBIs to win NL rookie-of-the-year honors in 2001.

“I’m the one who told Tony, with about 10 days left before the season, that it would be the stupidest thing in the world if you don’t put him on our team in 2001,” McGwire said. “And it worked out, I think, didn’t it?”

It wasn’t until the following spring, before Pujols’ sophomore season with the Cardinals, that Gammons was convinced Pujols had Hall-of-Fame potential.

Albert Pujols dug his right foot into the dirt, then his left, and nestled his deteriorating body into his famous stance.

“He comes back the next year, we’re gonna do a sit-down with him for ESPN, and the first thing he says is, ‘Well, there may be some guy here who’s coming to take my job, so I have to work as hard, if not harder, this year because your job is never safe,’” Gammons said. “And I thought, he just had one of the greatest rookie years in the history of baseball.”

Pujols went on to hit at least .300 with 30 homers and 100 RBIs for the next nine seasons, his 10-year run of .300-30-100 seasons the longest for a player at any point in his career.

The first baseman, nicknamed “The Machine” because of his consistent production, won NL MVP honors in 2005, 2008 and 2009 and led the Cardinals to the 2006 and 2011 World Series titles, wowing fans with his power.

“That was one at-bat you always wanted to watch because you never knew what you might miss out on,” said David Eckstein, the former shortstop who played with Pujols from 2005 to 2007. “Just his ability to barrel a baseball … he was one of the most dominant players to ever play.”

Eckstein was on second base in Houston’s Minute Maid Park for one of Pujols’ signature moments, his monstrous three-run homer off Astros closer Brad Lidge that turned a 4-2 deficit into a 5-4 Cardinals win in Game 5 of the 2005 NL championship series.

Albert Pujols was designated for assignment by the Angels. The future Hall of Famer was in the last season of a 10-year, $240-million contract.

“The shot heard ’round the world,” said Eckstein, the leadoff man on the Angels’ 2002 World Series team. “The sound off the bat was so loud, and then the crowd went dead silent. It was, by far, the coolest moment I’ve ever been involved in.”

There were no such moments for Pujols in Anaheim, outside of the few milestone hits that made him one of only two players, along with Hank Aaron, to reach 600 homers, 2,100 RBIs and 3,000 hits. Though he could still put a charge into a ball, knee and foot injuries and age conspired to drain the life out of his legs and bat.

McGwire, whose career was cut short by persistent knee injuries in 2001, said there is “no question” Pujols would have surpassed Bonds’ record of 762 homers if not for the injuries.

“When you mess with an athlete’s lower half, that’s the toughest thing to recover from, because no matter what surgery you have, you’re altering your body, and no matter what you do, something else is gonna give,” McGwire said. “It’s really hard to be a successful power hitter when you hurt both knees and both feet.

“Albert had speed, he used to steal bases and take extra bases,” he said. “Then he had foot and knee problems, and you started to see that stuff go. From then on, it was all heart and the love of the game that got him through the rest of his career.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.