The Angels are within their rights to fire Mickey Callaway, so why haven’t they?

When ESPN reported that New York Mets general manager Jared Porter had sexually harassed one woman, the Mets fired Porter the next day.

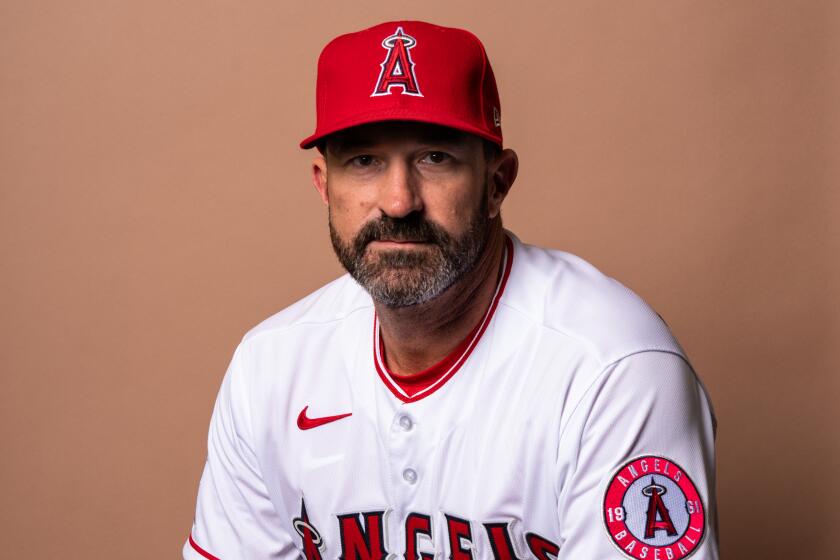

When The Athletic reported that Angels pitching coach Mickey Callaway had sexually harassed five women over the course of five years and three teams that employed him, the Angels suspended Callaway the next day.

The difference: Porter acknowledged fault to his team and expressed remorse for his actions, as Mets President Sandy Alderson said after firing him. Despite the publication of numerous electronic communications that appear to incriminate him, Callaway has denied the allegations reported against him, according to a person familiar with the matter, compelling the Angels and Major League Baseball to launch an investigation.

The parties expect the investigation to be completed shortly. On a conference call Wednesday to announce the trade for pitcher Alex Cobb, Angels general manager Perry Minasian declined to discuss any aspect of the Callaway situation, even who might serve as an interim pitching coach during the investigation.

Michael Waterstone, the dean of Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said he was unaware of any state law that would preclude the Angels from firing Callaway immediately.

“There are reasons to want to do an investigation before doing that,” Waterstone said, “to figure out the veracity of the claims. They may want to figure out, do they have any exposure on this? And a lot of employers, out of fairness to the individual, would conduct an investigation before taking definitive action.”

Pending completion of an investigation into allegations from at least five female reporters, the Angels suspend pitching coach Mickey Calloway.

The Angels could fire Callaway — or any other coach under contract — at any time. That would, in essence, require them to do what they would do when they release a player: pay the balance of the contract.

However, if they wish to fire him without paying off that balance, they would need language in the contract that permits termination for just cause.

Baseball’s collective bargaining agreement allows for a broad definition of “just cause.”

“Players may be disciplined for just cause,” the agreement reads, “for conduct that is materially detrimental or materially prejudicial to the best interests of baseball.”

Discipline generally requires a process. Players accused of domestic violence, for instance, are placed on administrative leave while the league investigates the charges.

But, because Callaway is not a player, the collective bargaining agreement does not apply to him. The “just cause” language in coaches’ contracts can vary from team to team and from sport to sport, according to an agent who represents coaches.

The agent does not represent Callaway. Speaking generally, the agent said contracts can cite such termination triggers as insubordination; commission of a crime; and abuse, sale or distribution of illegal substances.

None of those circumstances would appear to apply in Callaway’s case. However, the agent said, a clause that could apply would be one that would permit termination of a coach whose actions bring the team into public disrepute.

Callaway’s contract is not publicly available.

“If his contract says ‘can only terminate for good cause,’ part of the reason they might want to do an investigation is to determine that there is, indeed, good cause to terminate him,” Waterstone said. “And the Angels, in that case, would be protecting themselves for when he turns around and sues them for acting in breach of the contract.”

The Angels need to stand by their values and part with pitching coach Mickey Callaway after a report details his pattern of sexual harassment.

Former North Carolina State men’s basketball coach Mark Gottfried sued the school last year, alleging it had improperly cited “just cause” provisions in denying him an agreed-upon buyout. Gottfried currently is the coach at Cal State Northridge.

By suspending Callaway now rather than firing him, Waterstone said the Angels could be protecting themselves against a wrongful-termination lawsuit.

“Let’s say … it turns out these allegations were spurious or not true,” Waterstone said. “Then they essentially fired him without any good cause. A lot of it may have to do with what salary he is due to receive under his contract. But I think a lot of employers in this situation would do an investigation.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.