Angel Stadium sales price could be a lot less than initially advertised

When John Moores sold the San Diego Padres in 2012,

the sale price was announced at $800 million. The actual price was $600 million, but Moores got the headline he needed.

The league liked the higher price, since other owners could use it as a basis for comparison when time came to sell their teams. The buyers did not care. They knew what they paid, and they got the team.

That brings us to the Angels, and to the deal they are expected to clinch this week with the city of Anaheim.

When the city announced the proposed deal two weeks ago, the headline price for the sale of Angel Stadium and the surrounding parking lots was $325 million. Under the terms of the deal, the actual sale price figures to be less — possibly by half, according to two people familiar with the deal but unwilling to discuss it publicly because the Anaheim City Council has not voted to approve the documents that will determine the final price. There’s a sale agreement, set for approval Friday, and a development agreement, targeted for completion and approval next spring.

Among the several appraisals received by the city, the land was valued at up to $500 million, but that was with the Angels gone and the stadium demolished. The city could have invited developers to join the Angels in bidding for the entire property, in the interest of cashing in as much as possible and perhaps clearing the site for homes in a region with a housing shortage.

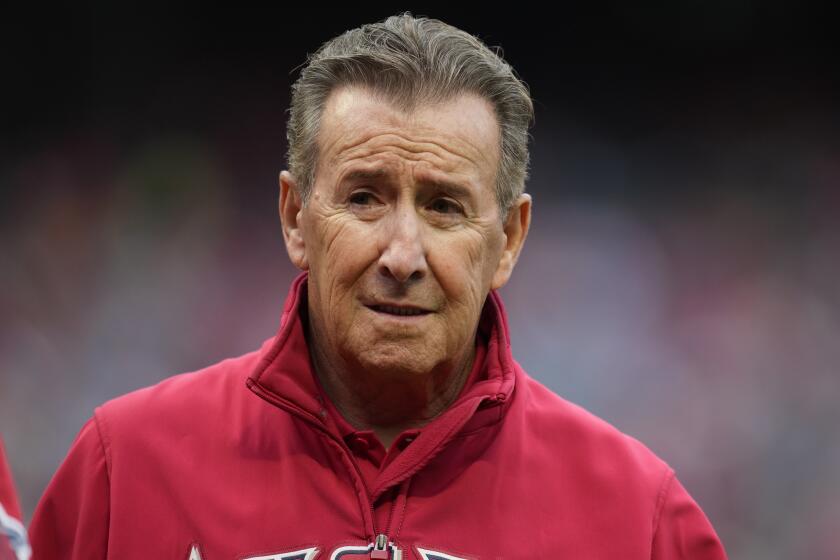

However, the city long has envisioned an urban village with Angel Stadium as the anchor. Mayor Harry Sidhu met with Angels owner Arte Moreno in January, and they agreed to pursue a deal that would keep the team in Anaheim.

In 2011, in the prime of his career, Jered Weaver agreed to a new contract with the Angels for $85 million. His agent, Scott Boras, advised him against taking the deal, and giving up what might be tens of millions of dollars, without at least soliciting offers from other teams. Ultimately, Weaver left an estimated $60 million on the table.

Anaheim has released a study that shows what Angels owner Arte Moreno and his partners might do with the Angel Stadium property after they buy it.

No interest in talking to other bidders, Weaver said, because I want to stay with the Angels.

That, essentially, is what Sidhu said.

So, not long after he met with Moreno, Sidhu steered an initial deal through the city council. The Angels had opted out of their lease, with no place to play after the 2019 season. The initial deal extended the Angels’ window to the end of the 2020 season, giving the city and team time to negotiate a long-term agreement.

At the time, neither Sidhu nor the city’s news releases disclosed the other part of that deal: if the sides did not reach a long-term agreement, the Angels could stay under the terms of the current lease.

For the option of selling the land at maximum value, that was game over.

The balance of power swung from the city to the Angels. If negotiations for a long-term deal collapsed, the Angels could control the land through 2038, not through 2020. If a developer wanted to build out the parking lots, the Angels could just say no.

So, if the city prioritized keeping the Angels over getting maximum value for the land, just what did Anaheim get?

The Angels committed to stay in Anaheim through 2050, with Moreno’s SRB Management Co. building a stadium or rebuilding the current one, and building out the parking lots with shops, restaurants, hotels and homes.

A team contributes to its community. The Angels and their foundation donated $2 million in grants and scholarships and donated 125,000 tickets this year, overwhelmingly within Orange County, team spokesman Adam Chodzko said.

Yet, the team will continue to play under the Los Angeles name, and there is nothing in the sale agreement that would prevent the team from calling its home Angel Stadium and dropping the “of Anaheim” suffix.

Moreno’s company, and not Anaheim taxpayers, would pay the cost of stadium construction. Moreno’s company also would assume the risk of development and would not share profits with the city.

If SRB does not build on the parking lots during the development window, the city can buy back the land, but Moreno’s company would profit because the value almost certainly would increase between now and then. If Moreno’s company wants to flip all or part of the land to another buyer, the city can only exercise “reasonable discretion” in approving or rejecting the deal.

If SRB does build, the city estimated it could generate up to $20 million per year in tax revenue. That estimate came from a firm commissioned by the Angels, Anaheim spokesman Mike Lyster confirmed.

SRB also could take advantage of credits offered by the city to encourage the development of affordable housing and parkland, and the employment of local labor.

In San Francisco, the Giants are building about 500 units of affordable housing as part of a similar live/work/play project adjacent to their ballpark, on a 28-acre site. The Angel Stadium site, not counting the stadium itself, is 133 acres.

Under San Francisco law, development of office space triggers a fee that the builder must direct toward affordable housing. That fee today is about $70 per square foot, or $90 million based on the Giants’ development plans. (The Giants’ actual fee is less because the law has changed since their project was approved.)

In Anaheim, according to councilman Jose Moreno, the city subsidized a recently approved development by crediting $100,000 for each unit of affordable housing. If SRB were to propose 1,500 units of affordable housing, and if Anaheim were to approve a subsidy similar to the one cited by the councilman, the Angel Stadium subsidy could be worth $150 million.

Bottom line: There is a headline price of $325 million, the maximum price. There is no guaranteed minimum price in the agreement.

Angels owner Arte Moreno is a baseball aficionado who had long been aware of Anthony Rendon’s talent. Striking a quick free-agent deal made sense.

Asked to explain how this deal satisfied the negotiating priorities he set out, Sidhu declined an interview request.

After former mayor Tom Tait torpedoed a proposed 2013 deal with the Angels, he ran for reelection in 2014 and trounced the field. Now, instead of leasing the parking lots to Arte Moreno for $1 a year, the city can make millions from selling the lots, with the hope of millions more in taxes from development, and a new or revitalized ballpark at no cost.

If the citizens of Anaheim believe the city should have done better on this deal, they can vote Sidhu out office next time he appears on their ballot.

Moreno, the councilman, believes the city should have done better. The last week was not a great one for him. He is a fan of the Dodgers, and on successive days last week the team missed out on Stephen Strasburg, Gerrit Cole and Anthony Rendon.

He does want the Angels to stay. He mused about the one Orange County man who might have driven a harder bargain: the agent who negotiated a combined $814 million in deals for Strasburg, Cole and Rendon.

“Maybe what we should have done at the start of this negotiation is to hire Scott Boras,” Jose Moreno said. “The city of Anaheim would have gotten a much better deal.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.