Apodaca: As proposals to ban books rise, librarians stand guard

My sons were little kids when the Harry Potter books burst on the scene. Like most of their young peers, they were enthralled.

We spent many happy hours reading together, giving voice to the colorful characters. Their love of the books was reinforced by the blockbuster films, Halloween costumes and themed parties that the stories inspired. My boys’ imaginations were on fire, their enthusiasm for the written word stoked.

Then I heard some rumblings. A few parents — not many, just a handful by my reckoning — were not so thrilled. From what I gathered, they believed that children were being influenced by the heresy of witchcraft. Where I saw a rich fantasy about a boy growing up, they saw indoctrination into dangerous beliefs, and they wanted the books banned from schools.

In the two decades since, there have been similar attempts to limit the ideas that kids encounter through literature. These efforts have come from both ends of the political divide — driven by liberal angst about racist words and stereotypes in classic novels like “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and from far right pushback on topics surrounding sex, gender and racism.

These concerns have spurred a continuing national debate about censorship, free speech and what type of content is appropriate at young ages.

But recently the effort to ban books has reached a fevered and worrisome pace.

The American Library Assn., in a public statement, reported “an unprecedented number of attempts to ban books” during the past year — in all, 729 challenges to library, school and university materials and services were recorded in 2021, resulting in more than 1,597 individual book challenges or removals.

The majority of those books, the ALA said, were by or about Black or LGBTQ people.

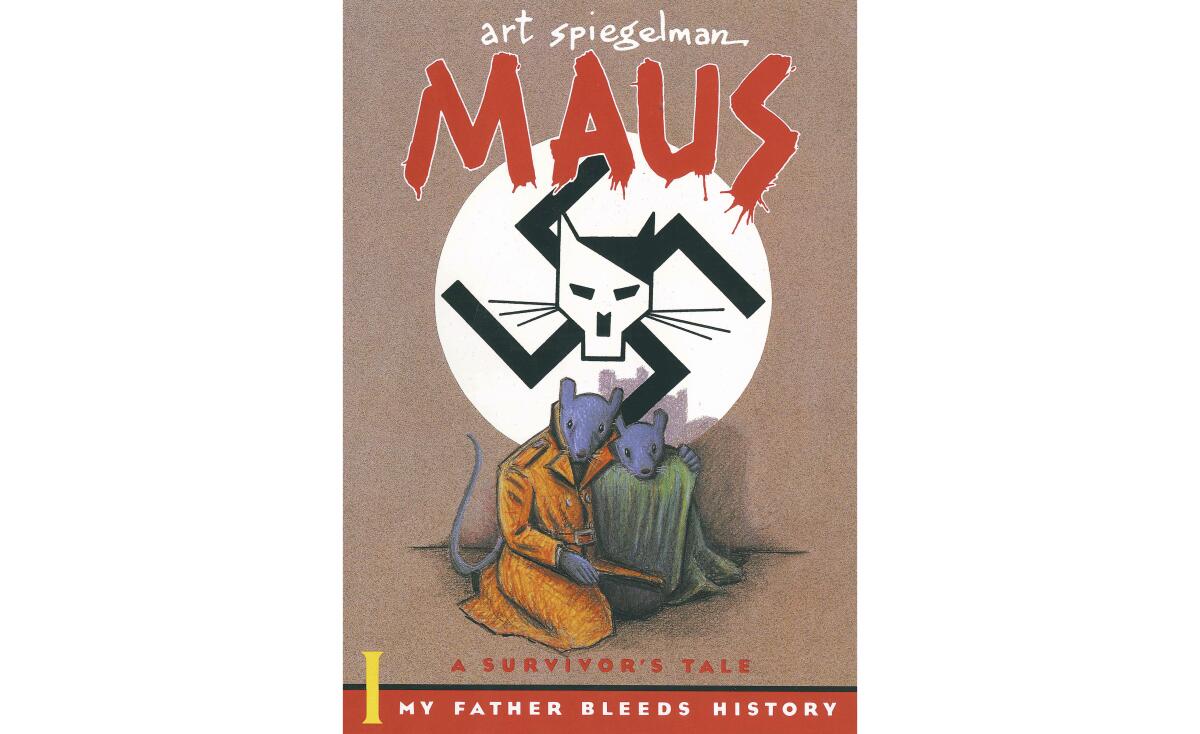

In one recent episode that generated headlines across the nation, a county education board in Tennessee voted to remove the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel “Maus” from an eighth-grade module on the Holocaust because it contained nudity and curse words.

This trend is developing despite overwhelming support for public and school libraries. A national poll by the ALA released last month found that seven in 10 voters oppose efforts to remove books from public libraries, and three-quarters of parents of public school students expressed a “high degree of confidence in school librarians to make good decisions about which books to make available to children.”

It also comes at a time when many schools have been making efforts to include more diverse perspectives and stories from minorities and historically disenfranchised peoples.

The New York Times reported that it isn’t just the number of challenges that has changed. It’s also the means used to attack certain books. Social media platforms are increasingly utilized in campaigns to generate support for bans, often by circulating lists of targeted titles and issuing emotional calls for parents to exert their influence, couching the issue as one of “parental choice.”

Another major factor ratcheting up the tension is that the pressure has expanded beyond school boards to statehouses and political races, the Times article said.

While an end to changing the clocks twice a year is almost universally welcomed, an Orange County sleep expert says daylight saving time would be the wrong option.

In Wyoming, a county prosecutor’s office considered filing charges against library employees for stocking books about sexuality. Some governors are also weighing in, calling for certain books to be banned and threatening librarians with legal action.

These developments have left schools in a sensitive position, despite well-articulated procedures for book selections and challenges.

The Newport-Mesa Unified School District, for instance, has set processes both for adding new books to school reading lists and for reviewing materials. If concerns are raised, those issues are run up the flagpole through school and district administration to determine if the books in question are indeed appropriate.

Public libraries are also feeling the pressure.

Tim Hetherton, the library services director for the Newport Beach Public Library, said he has seen only three or four book challenges over his 23-year career in the city’s library system. But any question or objection raised is taken seriously and thoroughly investigated, he said.

A few years ago, one library user complained that the library skewed too far to the political left with its selection of titles. In response, the library undertook a comprehensive inventory of its stock and used specialized software to determine political leanings.

The finding: a 50-50 split between left and right ideologies.

As Hetherton tracks the developments occurring in other communities, he remains committed to defending the open expression of ideas and viewpoints. Individuals can decide if they, or their children, should read certain works, he said.

There’s another facet to book banning efforts worth noting: They frequently backfire.

The Harry Potter books, still denounced by some critics, are by far the best-selling series of all time. After that Tennessee school district moved to ban “Maus,” sales soared.

But the most salient argument against the recent book-banning frenzy remains one of principle. To that point, I’ll let someone who has devoted his life to books have the last word.

“A long time ago, when I chose to become a librarian, I accepted the responsibilities of the profession,” Hetherton said.

“We believe in inclusion and free access to ideas. I feel that it’s up to me and library staff across the country to protect our cherished access to ideas.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.