Brea photographer uncovers hidden history of one of California’s most violent youth prisons

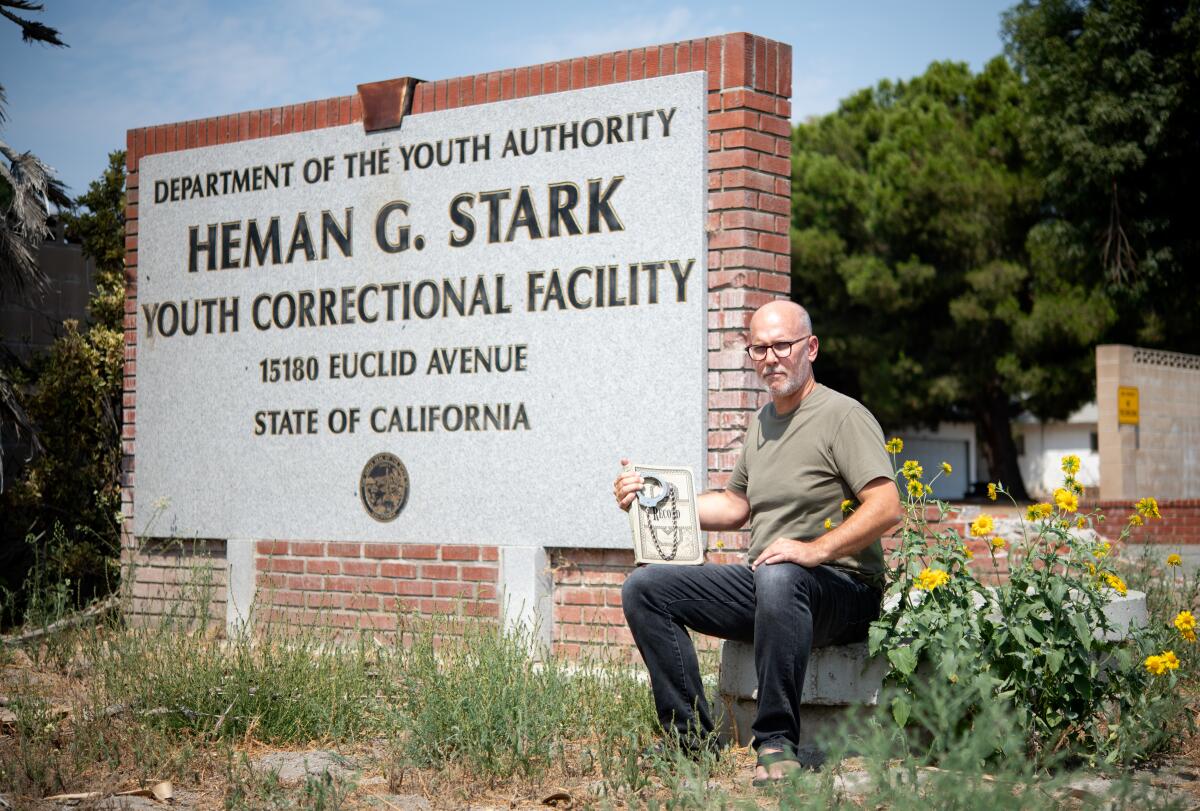

When Tony Espinosa’s fiance showed him a gallery of recent pictures from inside the now defunct Heman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility, also known as Youth Training School (YTS), roughly four years of memories from one of the state’s most violent youth prisons came flooding back to him.

One of the images among those shot by Brea-based photographer David Reeve depicts a brown sofa against a brick wall with a boxing trophy sitting on one of its cushions.

“I couldn’t even breathe,” Espinosa told the Daily Pilot during an interview Wednesday. “I couldn’t even talk. I couldn’t even tell her ‘that’s my trophy.’”

They immediately contacted Reeve, setting off a six-month journey to retrieve a lost artifact hiding in the state’s prison system. For Espinosa, it was a symbol of years of training, survival and triumph.

Tony ‘The Tiger’

Tony “The Tiger” Espinosa was a child the first time he strapped on a pair of gloves and knocked someone out. Whenever the monsignor at the Catholic school he attended caught wind of a beef between students, the priest would act as a referee and put on a boxing match with their classmates gathered in a circle around them.

As a kid, boxing was his life. But it became more than that after he got caught stealing booze from a neighbor’s shed in 1983 and was sent to Ventura County Juvenile Hall. Upon turning 18 and transferring into YTS, the sport became his ticket to survival.

“Believe it or not, there’s 365 days in the year [and] there was either a fight, a riot, somebody got killed, stabbed or something at least 365 days a year there,” Espinosa told the Daily Pilot. “Sometimes two or three times a day.”

Espinosa said several friends he met while locked up never made it to their release dates. But he joined the correctional facility’s boxing team, ultimately becoming its captain. His training helped isolate him from the constant violence around him and kept him out of gangs.

Being on the team also afforded him special treatment like better food and more freedom to roam YTS’ grounds than other wards. He had access to a full gym outfitted with some of the best equipment money could buy and world class trainers.

Espinosa wasn’t completely immune to the realities of living at YTS, though; he recalled getting stabbed in the leg once after confronting someone who had tried to steal from his cell. It was the holiday season, and as the car he was being transported in to receive medical care passed by Christmas lights hanging in front of people’s homes he realized he had been away from his family for three years.

“I think it was my first week there when a guy got stabbed in his eye,” Espinosa told Reeve in an interview shared alongside his photos of YTS. “His eyeball got ripped out. I don’t remember who it was, but they were fighting, and he got stabbed in his eye, and his eyeball landed right in between my two feet.”

Despite everything happening at the correctional facility, Espinosa’s boxing career flourished. He remained undefeated during his roughly four-year stint at YTS, culminating in a match against another boxer with a perfect record to decide the amateur light-heavyweight state championship. His opponent was “the toughest guy I had ever fought,” Espinosa said.

“After the first round, I knew I was winning,” Espinosa said. “I was in the zone. I wanted that championship trophy. I was going for his head.”

Special arrangements were made to allow his family into YTS, and they watched him win while surrounded by guards to protect them from other wards. Afterward, they all joined the warden for a steak and lobster dinner, a rare treasured memory out of almost four years of incarceration that Espinosa would otherwise prefer to forget.

He wound up handing the trophy over to the warden for safekeeping because it was a potential weapon. And Espinosa was so excited about getting released about six months later that he forgot to ask for it.

Espinosa continued boxing for a few more years and eventually moved on to start a family and a plumbing business. He and the rest of the world forgot all about the trophy until coming across Reeve’s photos almost three decades later.

“I was there for almost four years, and that place was hell,” Espinosa said. “It was hell. What went through my head was us having dinner with all of my family, my grandmother was there, my brothers and sisters. We’re laughing and talking and passing around the trophy. I really felt like I was home. I did not feel like I was in prison for that 20 or 30 minutes.”

Saving untold stories

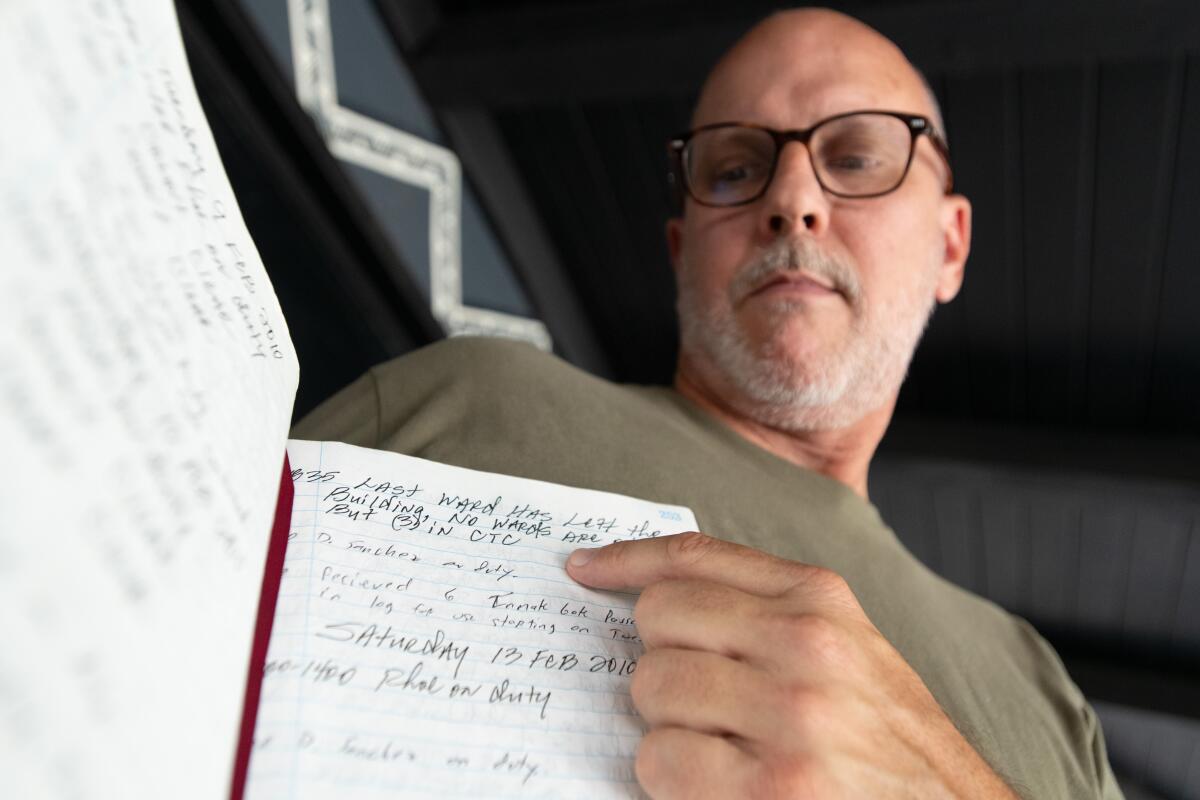

YTS was shut down in 2010 following years of reports of inhumane conditions and oppressive treatment in California’s youth prisons. The closure came 14 years after the murder of one of the counselors working at the facility, Ineasie Baker.

Reeve had been driving by YTS almost every day for years on his commute from Brea to Chino without ever realizing the significance of the abandoned building or his own family’s connection to it. After doing some research, he discovered that his grandfather had been a temporary warden at the youth prison, albeit only for a few weeks.

He reached out to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and hounded them for months. They eventually gave him permission to go into the dilapidated facility seven years ago to document what was inside.

Reeve had to wear a hazmat suit and respirator as he explored partially flooded rooms or navigated past collapsing ceilings and questionable staircases. Wherever he went, he encountered textbooks, billy clubs, classroom desks, handcuffs and more evidence of the former Department of Juvenile Justice’s complicated mission to both incarcerate and educate youth. Last summer, the state shut down its last two functioning youth prisons and handed over the task of locking up young offenders to county governments.

“My takeaway is that you’re dealing with a highly complicated situation,” Reeve said. “This isn’t just good guys and bad guys. It’s not as simple as black and white.”

Former wards and staff started reaching out to Reeve not long after he began publishing his photos online. The stories they shared with him include the account of a former YTS prisoner who went on to become a teacher at the facility after his release. Another documents the experience of Dr. Ashley Massimino, a psychologist at the prison who recounts masking her femininity while donning literal and figurative “armor” before each shift at the youth prison.

As of earlier this month, Reeve had shared as many as 18 accounts from people with some sort of connection to YTS, all told in the first person alongside images of the crumbling building. Aside from light editing for clarity, their words remain unaltered from their interviews with him, leaving the listener to make their own decisions about each narrator’s trustworthiness.

“These stories have been very much sealed,” Reeve said. “Previous to this project the only time you knew what was going on inside that institution was from a newspaper reporter or when the state would issue a report ... none of those would actually speak to the people who were there because they didn’t have access to talk to a ward who had gone through a suicide attempt.”

What began as an effort to sate Reeve’s curiosity wound up becoming both an obsession and a calling for him. People are still reaching out to him recounting events that otherwise might be forgotten, and he aims to keep publishing interviews with them for as long as he can.

Others, like Espinosa, describe long-lost mementos that may or may not be hidden away at YTS. Reeve plans on hunting down these treasures, like a plaque honoring a fallen officer, and returning them to their rightful owners. He’s also interested in expanding his mission by gaining access to other closed down prisons.

View this profile on Instagram David Reeve (@davidwreeve) • Instagram photos and videos

The Trophy

Espinosa’s trophy was spotted in a room of the administrative building, but it didn’t stay there. It wound up shuffling through the shuttered complex randomly as maintenance crews made their rounds. It took about six months of back and forth between Reeve, Espinosa and the CDCR before a worker who recalled handling it managed to retrace their steps and locate it.

Espinosa said little when the trophy was returned to him during a ceremony; he was too flooded with emotion to think clearly. And after everything he had done to earn and rediscover the memento, he was afraid to even lay hands on it.

“I was expecting the trophy to be like paper or something, and for it to not be real,” he said.

But once it was placed into his hands, he didn’t want to let it go. It’s now one of Espinosa’s most prized possessions, and he’s building a special case for it so it’ll be one of the first things people see when they walk into his home.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.